Tagged: fatherhood

One with the Father: A Trinitarian Meditation for Father’s Day

Preached at Valley Gate Vineyard, June 16, 2024 (Father’s Day)

20 “I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. 22 The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. 24 Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory, which you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 “Righteous Father, the world does not know you, but I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made your name known to them, and I will make it known so that the love with which you have loved me may be in them and I in them.” (John 17:20-26, NRSV)

In this passage, Jesus prays for the church, and in this prayer, he speaks about his relationship with his Father, how they are mysteriously one: the Father in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the mystery of the Trinity that the Father is fully God, the Son is fully God, and also the Spirit is fully God, each showing that they are distinct persons and yet, they are one, one relationship in each other and through each other.

Now, I am a theology professor. I get to teach folk about this stuff, and sometimes, let’s just say, students are less than thrilled to dive into the tough stuff. Most grant that there is something about doctrine that is important. This thing called truth; we are all big fans, and so, the Trinity is worth a nod to being fundamental. Now, that can all sound well and good, but it is also quite mysterious and abstract, and who has time to understand all that stuff? Sure, the Trinity is important; sure, it’s fundamental but it is also kind of fuzzy.

That Father and the Son are one, the Son in the Father, the Father in the Son—what does it mean to be at one? What is the Trinity trying to teach us (especially today on Father’s Day)? Isn’t all this oneness talk just impractical abstract mysticism? Are we right to ask, as modern people, is all this really useful?

And while we are at it, isn’t talking about God as a father a bit sexist, a bit patriarchal? Again, we, as modern people, are we right to ask: why should I look to this ancient book called the Bible, a book that has caused wars, sanctioned slavery, suppressed science, and supported sexism? What could we learn from looking at this old language of God as a Father? What can it possibly say to our experience of our fathers and, for some of us, our experiences as fathers and how this relates to God?

One time, I was camping on the shore of Lake Erie with a group of friends for our friend’s bachelor party. Of the group of guys, most were from our Bible college, all except one, who Craig knew from his work. Upon realizing this, my Bible college mates inquired about whether he was a Christian or not. The guy merely said that he “just wasn’t all that religious.” Another guy in the group saw this as an evangelistic opportunity. The conversation frustrated the non-Christian guy. He left and went over to where I was sitting. He was visibly annoyed, and I cracked a few jokes to lighten the mood. We chatted there under the stars, glistening off the gentle waves of the lake. I was smoking a nice Cuban cigar. Eventually, curiosity got the better of me: “So, I am curious; what do you believe about God?”

“Well, I don’t know. My father brought us to church, and he was an alcoholic jerk. The stuff he did to my mother and me…” It went on something like this, and I had to interject.

“I asked you about God, and all you have said to me this whole time was about your Father.” The guy paused. He had not realized what he was doing.

I don’t recall the rest of the conversation, but it illustrated to me just how important it is to think about how we talk about God. How we talk about God is always bound up with our relationships with other people. You can’t do one without the other.

I asked about God, and he immediately associated that question with his father. Why did he do that? Why did he connect them subconsciously?

This association between God and our fathers is something perennial in the history of religion and it is deep in the Western cultural psyche.

Almost everywhere that people started thinking about God, they started associating with God the qualities of their parents, particularly their fathers, and for obvious reasons. Our parents are the source of our bodily existence, the ones who care for us when we are the most vulnerable, and so, their example forms some of our earliest feelings of safety, security, and provision. They form our earliest thoughts on what is ultimate in life, what is right and wrong, desirable or undesirable.

And so you have these analogies that appear both in the Bible and other religions: God is like a mother because God creates us like a mother birthing her child or sustains us like how a mother nurses her child. God is like a father in that since usually men are the physically taller and stronger members of the household, God is powerful and protective like a father. Because of this perception of power, the leader god in most pantheons in most ancient religions is usually a father-god, not a mother-goddess.

Now, if that is all that is, surely with changing times where both parents work, and gender stereotypes are frowned upon, then yes, referring to God as a Father is out of date. After all, women can be strong, and men can be nurturing, and so on and so forth. But is that really what is going on in the Bible? (I would point out to you that there are actually a number of references to God as female and motherly in the Bible as well if you look for them). But the bigger question is this: Is God really just a projection of what human relationships are like? Or is God ultimately beyond all that? If we think of God as a father, how does God show us what he means by that?

And on the other hand are we so different from ancient people? Our culture still experiences something that ancient times experienced: conditional love, absent love, broken love.

According to Statistica Canada, in 2020, there were 1,700 single dads under the age of 24. Also, in 2020, however, there were nearly 42 000 single moms under the age of 24. There were 21,000 single dads between the ages of 25 and 34 in Canada in 2020 where there were 215 000 single moms. Now, there might be lots of reasons and qualifications for these statistics (there are lots of single-parent households that are healthy and happy, don’t take this the wrong way), but it is safe to say that we still, culturally, are much more likely to be missing the love our of fathers on a daily basis than the love of our mothers. And, of course, that says nothing about the many double-parent families where the children have strained relationships with the parents they know.

We still face the same things as the ancient world, just in different ways. In ancient Greece, in cities like Sparta, if a child was not acceptable to the father, it was quite common, even expected, for the father to expose and kill that child. The father’s acceptance was conditional on whether the child was good enough and strong enough. For folks in this culture, they thought it was necessary: men need to be strong to fight wars. Weakness could not be tolerated.

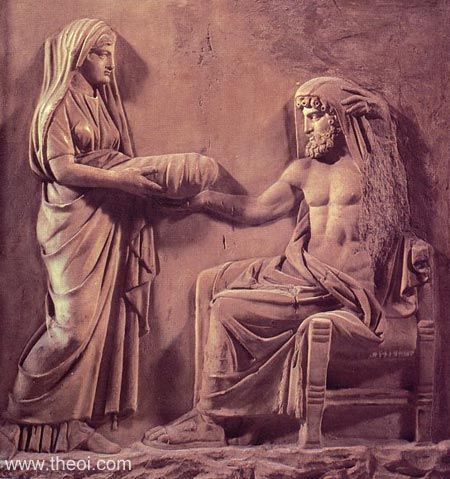

And this struggle to demonstrate one’s strength appears in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, there are two primordial Gods: the mother earth goddess, Gaia, and the father-sky God, Uranus.

They give birth to powerful monster gods called the Titans, the most powerful of which is Cronos, who resents his father’s rule and kills his father, becoming king-god. However, Cronos then becomes fearful that his children will usurp him, so he gobbles them up one by one after each one is born (Greek mythology is strange that way, I know).

However, one of his children, Zeus, is hidden from him and raised in secret, and it is Zeus who grows up to slay his malevolent father, assuming power to reign justly, at least for the most part. Zeus, however, in turn, fathers many illegitimate demi-god children, like Hercules and about 16 others in Greek lore, who grow up not knowing who their father is, often trying to do heroic quests to win Zeus’ approval.

Zeus slays his father, but he can never become a true father, it seems, in turn.

Deep in the religious consciousness of Greek religion is this conflict, this worry: If power is what makes a man, what makes a father, what makes a god, how can any son measure up? (But on the other hand, how can a father ever truly be a father either, if all he is obsessed about is power?) Or if the son is stronger, what is stopping them from replacing or usurping their weaker father, taking what their father has by force? And if that is the case, is Zeus all that different from Cronos? If power is what it means to be man, a father, or a god, then the more Father is like Son and Son like the Father, the more estranged they will be, the more they will fight, whether it is humanity to God or humans to one another. They cannot be at one.

I had this illustrated to me in one of the most profound movies on the effect of absent fathers I have ever seen. It is in the movie The Place Beyond the Pines. Ryan Gosling plays Luke, a motorbike stunt performer for a circus. He is a lone wolf, rough around the edges, a guy from the wrong side of the tracks. However, he learns that his ex-girlfriend had a baby, and it is his. He tells her that he loves her and wants to be for their child what his father never was: a provider that will come through for them. However, he admits that working for a circus does not pay well. He can’t afford the things he believes a father should be able to afford for his child. His girlfriend, however, just assures him that being there is enough. But Luke is afraid that he will be inadequate, just like his father was to him. So, his buddy tells him that if he wants to be a real man and provide for his family, he has to use whatever skills he’s got to do it. For him, it is his exceptional skills on a motorbike that could be used for something else: robbing banks and alluding to cops. Luke, in desperation, agrees. He robs the bank and speeds away from the cops on his bike almost effortlessly, and he is able to take that money and buy a crib and clothes and baby food and even take his family out on a dinner date. However, he realizes he will need more, so, he tries a double robbery, but it goes south, and in the mess of trying to allude to the cops, one cop, Avery, played by Bradley Cooper, shoots him and kills him, even though Luke is unarmed.

At this point, the movie shifts the main character from Luke to Avery. Avery, we learn, is a workaholic cop, being a cop is everything to him, despite him having a young family. For Avery, being a man means being a good cop. However, Avery is stricken with guilt over killing an unarmed man, something a good cop would never do. but Avery’s fellow cops cover up his fatal error, but this does not make him feel better as he learns just how corrupt some of his fellow cops are.

Moreover, he learns that Luke had a son about his son’s age and that the reason why Luke turned to crime was to provide for him so that his own son would be proud of him, the same reason Avery joined the police force, to make his dad proud of him. Because of the guilt, Avery can no longer stand to be around his own son, unable to be a father to his own son, knowing how he took some other boy’s father, punishing himself by denying himself a relationship with his own son.

The movie concludes years later. Avery is running for office, a workaholic relentlessly working for government reform, but doing this deep down to make hopeless amends for killing Luke. However, along the way, his son and Luke’s son, both teenagers now, both wayward and troubled from not having a father figure, meet and realize that while initially hate each other, Luke’s son sees the possibility of enacting revenge—they realize that they are the same: one had their father taken by the other, but the other never had his father to begin with, despite them living in the same house. And yet, ironically, sadly, the two of them show signs of becoming just like their fathers, one a reckless wonderer, the other a perfectionist.

The more Luke resented his father, the more he became like him, and this conflict, this estrangement continued from his father to him, but now from him to his son, who, just as ironically, ends up just like him. If our value as men, sons, and fathers is equated with our performance, we will not be at one with each other.

Think about that yourself. For many of us, we had good relationships with our fathers, but perhaps you did not. How has that affected you? Will we choose to see how our fathers are in us, whether this is good or bad?

Well, again, we like to think that we are better than all this ancient barbarism and mythology, but we are not all that different. The same human nature is within us, and there is the same realization: with so many of our relationships, especially ones as important as the ones between parent and child, we are not at one.

And there is an irony to all this with religion: We as a secular society believe that now that we are smarter, more educated, more technologically advanced, more politically organized…more powerful, we don’t need God. Isn’t secular society just one more attempt to kill Cronos all to end up just like him.

“God is dead, and we have killed him,” said the philosopher Nietzsche, declaring that to live in the modern world was to live with a rejection of God as an idea that was useful and meaningful to life. To live in a secular world is to live in a world that has pushed out God, religion, and even objective morality, all in the name of our own will to power. But even Nietzsche worried whether humans were indeed able to live without God.

We live, as George Steiner once said, with a “nostalgia for the absolute.” We live with an awareness that something is missing, something is absent, and for many of us, we live our lives trying to fill that void with something else, whether it is work, achievements, money, sex, or just mindless consumption and entertainment, whether it the socially expectable kind like Netflix or video games or ones less so like drugs.

I had this connection between God the Father and our fathers in a secular world illustrated to me in one of my favorite novels of my young adult: Fight Club.

Fight Club, for those who don’t know this cult classic, is a story about a man who works a meaningless job for a greedy company. His life has no purpose, so he finds himself unable to sleep, passing the time by ordering useless products from shopping channels. However, he meets a man named Tyler Durden, who convinces him to punch him one night after a few beers in order to make him feel better. The man does, and the two start sparing, punching each other. It feels therapeutic for them, so they start up a fight club in the basement of that bar.

Tyler Durden and the main character talk about their past and about God, and both realize that they had fathers walk out on them, and they feel like this is a reflection of what God is like, too. Other men join this fight club, fighting others as a way of expressing their rage over their meaningless lives. Tyler names their struggle in one monologue he makes:

“Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering…an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables—slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy [stuff…he says something else here] we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man: No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war; our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day, we’d all be millionaires, movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Other chapters of these fight clubs start opening across the nation, and Tyler Durden starts manipulating them into cult-like cell groups, sending the men out on missions to vandalize corporations, with the grand scheme of blowing up the main buildings of VISA and other credit cards and banks, effectively resetting civilization. Tyler believes that he is some kind of messiah figure for himself. The narrator explains Tyler’s motives this way:

“How Tyler saw it was that getting God’s attention for being bad was better than getting no attention at all. Maybe God’s hate is better than His indifference. If you could be either God’s worst enemy or nothing, which would you choose? We are God’s middle children, according to Tyler Durden, with no special place in history and no special attention. Unless we get God’s attention, we have no hope of damnation or redemption. Which is worse, hell or nothing? Maybe if we’re caught and punished, we can be saved.”

Do you know people that say they don’t care about God but are living like they are desperately trying to get God’s attention?

And in a secular world, where we live either ignoring God or feeling God’s absence, as well as living in a world where masculinity, our worth as fathers, is so often defined by power as well as the money we make and the stuff we own or achieve, relationships like the ones between child and parent will be marked with conditions and expectations, caught in this vortex of conflict, competition, and estrangement.

If God is not love, no matter whether we run for God, ignore him, disbelieve him, or hate him—if God is not love, we will end up just like him: unloving ourselves.

I say all this to say that there is a longing deep in the heart of humanity, a longing for meaning and purpose, for acceptance and love, and this longing is symbolized in God the Father so often because of the role our fathers play, whether for good or ill, and it is a longing for oneness.

We have to ask a question fundamental to our future as humans: who is this God that we so often look to as a father? Does God care more about ruling unquestioned than loving his children for who they are? Is God the kind of God that will reject us if we don’t measure up? Will God ignore us if we ignore him? Is love conditional? Is oneness possible? Oneness between God and humanity and humanity with each other?

Well, the story of Scripture tells a different story of God as Father. To confess Christ is to attest to how we have found ourselves in a story where the Creator of all that is chooses to create people in God’s image and likeness. Image and likeness was a way of talking about one’s children. A child is in the parent’s image and likeness and so, God makes all people to be his children, making them with dignity, designing them to reflect his character of love as the way they can most authentically be themselves.

This God reveals himself in history, calling Abraham out of his father’s household, out of idolatry, and into redemption, promising to bless and protect him.

This God led the Israelites out of Egypt, a people oppressed and enslaved under idolatrous tyranny, and God told them that out of all the human family, Israel is to be his firstborn, a nation that has a unique purpose in reflecting God to the nations around it.

This God says God is One, the I am who I am, the living God, and this One God longs to be one with us.

This God says that he is like a father. However, even more than that, God is the perfect father, and God, as this perfect father, beckons us home when we have rebelled against him.

And so when we look at the narrative of the Bible, we see this One God revealing who God is in this pursuit of being at one with us in a way that mysteriously takes on—for lack of a better word—different dimensions to God’s self: the God who is beyond all things, infinite, transcendent, and almighty, but is also the root of all existence, the breath of life, the presence of beauty, one in whom we live and move and have our being, the movements of love, known as Spirit.

As the narrative shows, these dimensions relate to one another. God sends his messiah, the king, but a king that is more than another human king; he is God’s only begotten Son, one with the Father. There is no conflict between Jesus and God because they are fully one with each other to the point that when you look at Jesus, you see the visible image of the invisible God. God is not a distant God. He is with us.

The Father sends the Son, Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly enfleshes the presence of the God Israel worshiped but also fulfills the longing for righteousness, this reconciling oneness with all things Israel was called to, and Jesus does so through sending the Spirit.

This story clashes with human sin, however, and it comes to a particular intensity when people reject Jesus’ invitation to step into the oneness of God. John says at the beginning of his Gospel: “The world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him.” We know how this story goes.

Jesus died on the cross, executed by an instrument of imperial oppression orchestrated by the corrupt religious institution seeking to preserve its own power, but also betrayed by the ones Jesus was closest with, his own disciples and his friends. The cross discloses the tragic depth of our tendencies to refuse to be at one with God and others, even when literally God is staring at us face to face.

But it is in these dark moments that God showed us who God is.

For Jesus to die one with sinners, yet one with the Father, reveals God’s loving solidarity with the human form—our plight, no matter how lost or sinful. God chooses to see God’s self in us and with us, never without us. God chooses to bind himself to our fate to say, “I am not letting you go.”

To be a part of the family of God is to trust in Jesus Christ; it is to remember that in these moments of condemnation, we have been encountered by the presence of the Spirit, a love that invites us to see that we are loved with the same perfect love the Father has for his own only begotten Son. The same love that God has for God in the Trinity, God has for sinners, for you, and for me. God is not going to give up on us.

Paul says it this way, “If we are faithless, God remains faithful.” Why? “Because he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim. 2:13).

That is the truth of the Trinity. Trust this. God has made a way for him and us to be one as he is one.

And if God is like this, this suggests ways our relationships can be healed and improved.

Can this propel us to love our fathers more, not merely for all that they have done for us (or have not done for us), but to love them for who they are, to love them as God loves them, to see ourselves in them and reckon with that, with thankfulness, with forgiveness, with gratitude and grace?

Can this change how we think about our own children? If God sees himself in us, can we empathize more with them, seeing ourselves in them, rather than just making sure they shape up to what we expect? To be there for them, love them for who they are, and the journey God has them on.

And God says, “May they be one as we are one.”

Let’s pray…

Fatherhood in Flux: Ephesians 5 in Changing Times

Pew Research, one of the largest sociological research groups in North America, surveyed mothers and fathers. Fifty-seven percent of fathers described being a father as “extremely important,” which was virtually identical to the women surveyed (58%). However, most of the moms surveyed said they did “a very good job” of raising their children; among the dads, just 39 percent said the same.

On the whole, fathers care about being fathers at the same rate as mothers care about being mothers, but a significant gap exists in how fathers feel about how they are doing at being fathers. Most fathers feel like they aren’t great fathers. Why is that?

I read an interesting article coming up to this father’s day by Daniel Engber from the Atlantic (I think the Atlantic writes probably the best articles on social issues out there, in my opinion). The article is entitled, “Why is Dad so Mad?” He writes,

Everybody knew that dads used to earn a living; that they used to love their children from afar; and that when the need arose, they used to be the ones who doled out punishment. But what were dads supposed to do today? In former times, the definition of a man was you went to work every day, you worked with your muscles, you brought home a paycheck, and that was about it… What it is to be a man now is in flux, and I think that’s unsettling to a lot of men. Indeed, modern dads were left to flounder in a half-developed masculinity: Their roles were changing, but their roles hadn’t fully changed.

They are left in a kind of lurch. Fatherhood is in a state of flux, retaining some conventional patterns but scrapping others.

I was reminded of this just this morning. My wife called me into the room. “What is it?” I said. She pointed to a spider on the wall. Apparently, in our marriage, it is the man’s job to kill the spider.

I jest, but many men feel seriously caught: if I work too much, as many jobs are demanding, this is no longer considered virtuous, and I am seen as a workaholic, neglecting my family.

If they work too little, society could perceive them as a deadbeat or lazy, particularly by the older generation that built and achieved so much.

Society used to value a man’s more forceful presence in discipline, but most parenting books have denounced harsher forms of discipline.

Women have made inroads in the workforce, but men have not gravitated the same way to homemaking or childcare, traditionally female roles.

There are increasingly fewer jobs that require physical strength. And increasingly, fewer fields of work are considered male careers.

It has left some men wondering: what do I contribute to my family or in my marriage? And this has many men feeling like they have lost their place in society and in the home. They don’t feel valued. They don’t feel what they do has value, or they don’t feel like they are successful in doing it. Fatherhood feels like it is in a state of flux.

In the wake of this, political groups have attempted to capitalize on this feeling of instability and nostalgia for the good old days. The movements by Jordan Peterson, who dies the existence of systemic sexism, or Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson have tried to say that there is a war against masculinity wagered by feminists and liberals and other monsters under the proverbial bed of culture. These guys have made a lot of money saying what they are saying because this is a message a lot of men want to hear.

However, probably the more accurate explanation is that with the cost of living going up so much compared to what it was decades ago and wages not increasing in proportion, the idea of a single-income household that owns their own property can have a designated stay-home parent, is becoming extinct for the average Canadian, and with it that male role.

Culture is in a state of flux. And when people feel this unease, this displacement of identity, it is very easy to look for someone to blame.

For many Christians, this has caused many to recede into nostalgia, longing for the days when everyone went to church, or when there was prayer in schools, when there was allegedly no divorce, or when, allegedly, everything cost a nickel (why was everythin always a nickel, by the way?).

Nowadays, I’m nostalgic for when gas costs a dollar a litre.

The text I am going to read today is a text that has often been misused by Christians. It is a text we have so often read, wishing to get back to the way things used to be when fathers’ and husbands’ roles were clear and revered.

It is really one of the most important passages on being parents and spouses, as well as being fathers and husbands, in the New Testament, but we often forget that the Biblical writers were writing for matters in their own day. They were writing because their situations were in flux also. We forget that.

It is Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, chapter 5, what is often called the household code. I am going to first read this passage, but then we are going to ask some questions about what this means, both in the ancient context and what it means for us today:

21 Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ.

22 Wives, be subject to your husbands as you are to the Lord. 23 For the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is the head of the church, the body of which he is the Saviour. 24 Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also wives ought to be, in everything, to their husbands.

25 Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her, 26 in order to make her holy by cleansing her with the washing of water by the word, 27 so as to present the church to himself in splendour, without a spot or wrinkle or anything of the kind—yes, so that she may be holy and without blemish. 28 In the same way, husbands should love their wives as they do their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. 29 For no one ever hates his own body, but he nourishes and tenderly cares for it, just as Christ does for the church, 30 because we are members of his body. 31 ‘For this reason, a man will leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.’ 32 This is a great mystery, and I am applying it to Christ and the church. 33 Each of you, however, should love his wife as himself, and a wife should respect her husband.

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. 2 ‘Honour your father and mother’—this is the first commandment with a promise: 3 ‘so that it may be well with you and you may live long on the earth.’ 4 And, fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord.

5 Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as you obey Christ; 6 not only while being watched, and in order to please them, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart. 7 Render service with enthusiasm, as to the Lord and not to men and women, 8 knowing that whatever good we do, we will receive the same again from the Lord, whether we are slaves or free. 9 And, masters, do the same to them. Stop threatening them, for you know that both of you have the same Master in heaven, and with him there is no partiality.

So, let me pause for a moment. Did some of those words make you uneasy a bit (particularly the submission and slavery parts)? Did some of those words sound agreeable (like the love parts)? I imagine most listeners will have mixed feelings reading this passage.

Perhaps you know this passage well. Maybe a pastor told you this is God’s pattern for marriage for today. Maybe you believe it is.

But, if this passage was giving us an obvious, clear, and timeless definition of marriage and parenting, why does it tell husbands to love their wives in order to make them holy and without blemish? Is Paul saying all women are unclean? Or is that what Jews assumed in that culture? May Paul is speaking in a way his audience would have understood.

It also says that wives should submit in everything. Should wives do that today? Aren’t there stories of women who did listen to their husbands and God was honoured, like Abigail or Rachel or Tamar. Maybe Paul is reacting to a certain circumstance woman in Ephesus face.

Sadly, this passage has been used to say to women that they cannot question or disagree with their husbands. It has been used almost like a club to clobber some people.

Maybe this passage brings up painful memories. I have dealt with women who were told that they had to submit to their abusive spouses because that is what this passage means. Let me be clear and say that whatever this passage means today, it does not mean that.

This passage also mentions slavery. It tells slaves to obey their masters with fear and trembling. I have heard some preachers say that this passage applies to bosses and employees today, but I just don’t think that is the case. There were day-labourers in the ancient world. But more importantly, as an employee with rights living in a country with employment laws, I just don’t think I should obey everything my boss says, let alone with fear and trembling.

But worse still, this passage has been used to justify slavery rather than the good news of God’s kingdom that Jesus announces: “freedom to the captive, that the oppressed can go free” (as he says in Luke 4).

For five years, I pastored the First Baptist Church of Sudbury, which had historic roots in the Social Gospel. The church historically led the charge for the miners of the city to have employment rights, safety standards, and eventually unions. They believe working to improve human life was an aspect of the kingdom of God. I think they were correct.

So, how do we understand this important passage today? How do we understand it as offering words that can build us up?

This will be a bit of a technical sermon (if you have not realized this already). I don’t know if you have met me, but I kinda like to go deep with my sermons. I do this because if we are going to become the fathers and husbands God wants us to be (and of course, this goes for all Christians as well), one vital way we get formed for that purpose is by meditating on God’s word, understanding it rightly, not in facile, careless ways.

Just like navigating what it means to be a man or a father in today’s world, God’s Word takes wisdom and work. So often, the church has assumed that the Bible is always so clear and straightforward it makes us ill-prepared to live in a world that isn’t.

Many want to go to the Bible to escape just how messy the world is, hoping to find a place that is black and white and clear, and there are some passages that are very clear, don’t get me wrong. But often, if you have read through the Bible, you see a lot of passages that cause you to have questions. Some that, at face value, don’t sound all that redemptive. In those cases, the path from what the words on the page say and what it means for us today is not straightforward.

Part of the reason for that is that the Bible was written not as an escape from the flux of history but written in its very midst. It was not written despite our humanity. It was written by humans for our humanity.

The Bible is a complex thing, and it’s complex because life is complex. And if we care about God’s word, we have to be willing to put in the effort to study and think about it in all its depth. It’s only then that its richness is fully appreciated. It’s only then that we realize that God isn’t trying to save us from the complications of life. God is trying to meet us there, in its midst, gently moving us forward in grace.

I sit on the board of an organization called the Atlantic Society for Biblical Equality. It is an organization that was founded by Hugh McNally and Harry Gardner to promote that men and women are made equal in the eyes of God and that when the Scriptures are considered in their fuller context and meaning, it teaches equality in marriage, that women can serve as pastors and things like that. I would encourage you to become members and support the work (perhaps the church could even be a supporting church partner in its mission).

This is one passage that people stumble over. I know people that are content to ignore a passage like this. But as Christians, that is just not a good plan, and so, our work as ASBE is to help Christians understand the Bible better.

My advice is that we need to study the Bible and study the difficult texts: Find the Bible’s meaning in the flux of history because that can really help us understand what it could be saying to us today.

So with that very long introduction, let me ask this: what was going on in Paul’s day that he needed to write this passage?

Well, the Apostle Paul is writing to the Ephesians, a Greek city in modern-day Turkey. It was a very important city both for Greek culture and the church. The Christian church had grown rapidly there, comprising of both Jews and Gentiles coming together, and that had caused some issues. The beginning of the letter speaks about how God’s household is where both Jews and Gentiles come together as one under God in Christ. Later in the letter, here, Paul turns to talk about what individual households could look like through the love of God in Christ. Here, if we do some digging, we find that Ephesus and the church there were experiencing their own state of flux, and Paul had to navigate that.

1. Christianity in Ephesus was in Flux

Christianity came on the scene in the ancient world and caused a profound social change. You see, Christianity preached the individual responsibility of all people to repent and believe in the one true God revealed in Jesus Christ, and this proclamation saw Jews and Gentiles, men and women, adults and children, wealthy individuals as well as slaves seeing the gift of the Holy Spirit, and people trust this and are justified.

In the ancient world, however, if you were a wife, a child, or a slave, your obligation was to worship the god of the head of your family, your father and master. If you were Roman or Greek, you were expected to follow the local gods. Christianity did not uphold this, and it caused friction.

Jesus warns about this in Matthew chapter ten. Jesus says that I have not come to bring peace but the sword, which is kind of a strange thing for Jesus to say. What does he mean? He speaks about how households will be set against one another, and if you are loyal to your family members more than Jesus’ way, this is not taking up Jesus’ cross. In other words, you are not a true disciple. For Jesus says, “Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.” Jesus isn’t saying he is going to cause literal wars, but rather that the way of Jesus is going to cause social upheaval, and any peace that means people can claim loyalty to their families against Jesus to please them is not true peace. It isn’t the peace that Jesus’ way offers.

Well, this insistence soured marriages and split families. Christians were viewed as traitors. Paul notes in his first letter to the Corinthians that spouses were leaving and deserting their partners over their change in religion, but Paul tries to say to Christian spouses to do their best to keep their marriages if they can: if their spouses leave, that’s their decision, but for the Christian spouse, commit to working it through, loving the other, hopefully winning them over. That is a good witness to the Gospel.

This is a thing Paul has to keep reiterating. In his letter to Titus, he says to young women to love their spouses so that “the word of God will not be maligned.” Paul’s letter to the Colossians chapter 4, just before it gives a similar household code, says that Christians need to walk wisely in how non-Christians are seeing them. 1 Peter similarly advises Christians to live in a way that prevents slander.

Christianity in the Greek and Roman world was being perceived as a group of people that were disloyal to their nation, to their marriages and families, and therefore were out to ruin society. There were rumours that Christians were cannibals because they ate flesh and drank blood when they got together for worship. Christians were thought to be atheists because they refused to worship the gods of their communities.

For many, Christianity was perceived as strange and even dangerous. Now, while it was true that Christians opposed the worship of Greek and Roman gods and opposed the ways of the emperors, it wasn’t true that Christians hated their families. Far from.

We have to appreciate the irony: today, we look at Christianity and the way things used to be, and we think it’s our culture that has caused all this disruption and flux. For Ephesians, they believed their culture’s values gave stability, and they saw Christianity as causing the disruption and flux. Our contexts are very different.

And so, this helps us understand the statements in the New Testament, where the Apostles keep telling Christians to honour the Emperor (even though the Emperors were immoral people), submit to authorities (even those that were brutal and corrupt as the Roman powers), leave peaceable lives, and so on. Those are passages that also don’t straightforwardly apply today because we live in democracies where we can choose our government, whereas, in the New Testament, they couldn’t.

The Apostles were doing everything possible to prevent Christianity from being perceived as a threat to the well-being of their home communities. They are trying to walk this tightrope of the faithfulness of Jesus and peaceableness with their families and fellow citizens. What were they worried about? Its something we just aren’t worried about in our country:

The Apostles did not want to be perceived as an insurgent movement as they spread the Gospel. Why? Revolutions ended in violence, with Roman soldiers slaughtering anything that could be perceived as a rebellion or disloyal to the Empire, and so, the Apostles tried to be wise in portraying Christianity as upholding certain social mores that Greeks saw as fundamental to social wellness.

What were those? Well, one of those was the Greek household code.

2. Ephesian Culture Believed Men were the Heads of their Households. Paul believed Jesus was the Head

And so, the second important aspect of Paul’s context was the Greek understanding of marriage. Ephesians believed it was good and proper for the husband and father to be the head of the household. The husband was often the educated one, legally was the one who managed the finances, and he was the one that procured the income for the family. Often the man was the religious representative of the family as well.

Because of this, he was regarded as the authority of the family, and Ephesians felt it was only good and proper to have wives, children, and slaves living in complete submission to the family’s leader.

However, men in Ephesian culture were regarded as the heads of their households, and as such, they were afforded power and privilege. Wives, children, and slaves were their servants, all for the purposes of affording them a better life. Husbands had little to no moral obligation to their wives and could act with a great deal of self-interest.

If the Apostles attacked this teaching too forcefully, a lot of women, children, and servants could find themselves without a roof over their head or worse. It wasn’t that the Apostles were afraid to sacrifice for their faith, but they were trying to be prudent to not pick unnecessary battles. In their judgment, in this context, which is different from ours, they choose a cautious and more subtle path.

Women did not have legal rights, no sources of income; there were no women’s shelters; there was no such thing as unemployment insurance or alimony in a divorce. These are things our culture has created, and if we are tempted to see these as an obstacle to living this passage, we must look to the history of Christian suffrage advocates and Christian abolitionists, Christians that have looked at how humans are made in God’s image and said our laws should reflect justice and equity.

Our culture has been influenced by 2000 years of Christian proclamation; Ephesian culture was not. That does not mean we are always better, but it does mean we are in a very different place.

Paul was dealing with a world that operated under certain conditions, things that the culture took for granted as the norms of how things functioned, while Paul was against things like slavery (he was a Jew, after all, that knew full well the stories of the Exodus, where redemption meant liberation from physical oppression), he also realized that for some people, slavery was their sole means of provision or that to oppose slavery in a revolution could end with Roman legions coming and killing everyone involved with a revolt.

We have to do this in similar ways today: We know, for instance, that our use of fossil fuels is not good for the environment, but for many of us, we still have to own gas-powered cars or have homes that use oil. If we tried to just rid Canada of all fossil fuels right now, that probably would leave a lot of people without transportation and without heat in the winter, so we are trying to transition off fossil fuels. I don’t know if we are doing a good enough job of that, but that is a topic for another sermon.

So, what Paul does then, is try to word the Christian life in as close of terms as possible to the way Ephesians understood marriage and parenting and managing their homes. He meets them where they are at and how they understand things, but he adds a Christian twist to it. He sows a seed of Christ-like transformation in it.

And this is where we really miss the point of the passage when we refuse to read the Bible in its historical context.

Let me read one of the more well-known household codes in Greek culture. Ask yourself, how is Paul’s version different from this? This is from Aristotle’s Politics:

Of household management, we have seen that there are three parts—one is the rule of a master over slaves… another of a father, and the third of a husband. A husband and father rules over wife and children, both free, but the rule differs, the rule over his children being a royal, over his wife a constitutional rule. For although there may be exceptions to the order of nature, the male is by nature fitter for command than the female, just as the older and full-grown is superior to the younger and more immature… [W]hen one rules and the other is ruled we endeavour to create a difference of outward forms and names and titles of respect… The relation of the male to the female is of this kind, but there the inequality is permanent.

Both Paul and Aristotle talk about husbands and wives, fathers and children, and masters and slaves. That’s how we know that Paul has something like this in mind for the context he is writing in. Did you spot some of the differences?

Aristotle talks about the rulership of all three. Men rule over women. Why? Because men are more intelligent by nature. They are, by nature, superior. They live in permanent inequality, and that inequality is a good thing.

Is that what Paul believed?

Paul is a Jew, and he knows that men and women are both in the image of God. He knows that if women are not equal to men, it is not because of nature but because of sin. The curse of Genesis 3 was that women’s desire would be for their husbands, but men would rule over them.

We have to ask ourselves: is it the church’s job to uphold the curse of sin? Or is it the church’s role to undo the effects of sin in this world with the power of salvation?

Paul says in Galatians, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, male or female, slave or free, all are one in Christ Jesus.”

If we look at Paul’s writings, we see that he had women leaders spreading the Gospel with him: church leaders like Chloe and Nympha, Pheobe (a deacon from Cenchrea), Eudia and Synteche (apostolic leaders along with Clement), Junia (an apostle listed that the end of Romans). If you have not heard those names before, look them up. Paul very much believed that the Spirit was moving to bring about equality in the world broken by sin.

We need to keep that big picture in mind when we interpret these passages. And when we do, the point of these passages of today becomes clearer:

Ephesians 5 begins with Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ. When it gets to the next line, it actually uses the same verb as this sentence: Be subject to one another… wives to your husbands. In other words, wives are doing something all Christians, men, fathers, and husbands included, ought to be doing too. Yet, so often, we preach this passage as if the burden is on women to do something unique to them.

Aristotle’s view of headship in the family emphasizes male rulership; Paul takes that notion of headship in God’s family and emphasizes mutual submission.

The Greek household code said men did not have to care for their wives, children, or slaves beyond food and shelter. Families served the man’s own self-interest. Paul says things like this in his household code:

Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her.

Husbands should love their wives as they do their own bodies.

He who loves his wife loves himself.

Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger.

Masters, know that both of you have the same Master in heaven.

Aristotle emphasized authority; Paul introduced accountability. Which one do you think then is the principle that applies to us today?

3. Jesus’s Love is the Pattern for Parents

Jesus told his disciples that “anyone who wants to be first must be the very last, and the servant of all” (Mark 9:35).

In speaking to them about the authority, he said,

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be your slave—just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Matthew 20:25–28).

Paul summarizes the pattern of Christ in Philippians chapter two when he says,

4 Let each of you look not to your own interests but to the interests of others. 5 Let the same mind be in you that was[a] in Christ Jesus,

6 who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

7 but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

8 he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

And so, in a culture where men were assumed to be the heads of the household, Paul, in essence, says, “Okay, men, if you want to be the head of the household, then be one like Jesus. Be ready to give up everything for your family.”

But that is not some new way to reinforce male power. It is consistent with what all Christians are called to do. Notice the principle that Ephesians chapter five begins with: Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children, and live in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God (v. 1-2).

This is the guiding principle for what Paul says in this entire chapter, and it says all Christians are to live self-sacrificing love towards one another, and when we come to verse 21, the guiding principle for the household code, Paul says all Christians are to submit one to another. The household code is merely applying these to the way Ephesians needed to have it applied in that context. But ultimately, submission, respect, service, and accountability¾these are things all Christians ought to be doing for each other, regardless of gender.

It is funny how we have looked at Ephesians chapter 5, and we have tried to apply it to mean something more like the philosophy of Aristotle than the way of Jesus.

If we defined authority in Jesus’ way, we would give up our authority, not hold onto it.

If we define what it means to be a man through Jesus, we won’t be worried about how we can get power out of our marriages and families, power over our wives and kids. We will ask ourselves: How can I serve them? How can I even submit it to them? What sacrifices do I need to make in order to love them better?

That might mean doing something things that our culture, perhaps even our church cultures, might view as not very manly.

When Meagan and I were first married, we had just bought our first house, a little townhouse in Bradford, one hour north of Toronto. We had our first child, Rowan, soon after moving in.

Meagan was teaching at a Christian school, and the school wanted her to upgrade her teaching degree to a full Bachelor of Education. So, she used her mat-leave to go back to school full-time.

I was also in school, working on my doctorate. I was between work, and I eventually got a contract as a pastoral intern at Bradford Baptist Church, a few hours a week.

But with Meagan in school in an intensive program, I had to pivot to caring for Rowan most mornings as well as do cleaning and some cooking.

Can I confess something to you? I am just not as particular about cleaning as my wife is. If there is a dirty spot on the counter, I don’t notice it. My wife enters a room, and it is like radar detection. But in order to have a household that felt orderly enough that my wife did not feel stressed about, I had to learn how to clean better.

Admitfully, after 13 years of marriage, I still am not there.

Of course, not having a full-time job, I got comments from family members: “So, when are you going to get a real job.” The implication is that my current situation was not what a man, a biblical husband, was to do. And I felt feelings of worthlessness, staying home, and caring for our son.

I had learned to equate my worth as a man and father with work and money.

I had to come to a point and say, but what does my family need? It is not about fulfilling some expectation of what a man or a husband or a father is according to our culture or even our church cultures. It is about asking our families, “what do you need?”

What does that mean for a world that is in such flux? Well, it is going to mean something very different for every couple and family.

It means that whatever life entails, it probably is not going to be easy. It means navigating decision-making, household work, finances, and childcare with fairness, with mutual submission.

And that takes sacrifice, and that is what we are celebrating today on Father’s Day. The ways our fathers have sacrificed to show their wives and children they love them.

For many of our fathers and grandfathers, these sacrifices fulfilled a traditional need, but for the younger generations, these sacrifices might look different.

Whether it is working a tough job away from home or working as a stay-home dad, whether it is mowing the lawn or cooking dinner, driving the kids to soccer or reading to them when they go to bed, there are little acts of service that show your families how much you love them.

The tasks may change, but love does not.

Paul says that when we do this, we are reflecting the reality that God is showing us in Jesus Christ, who loved us so much that he came in human form, became a servant, and became obedient even onto death, death on a cross.

Can I just say that Jesus knows a thing or two about changing to love those he cares for in the way they need it?

Fathers, husbands, men in the audience today, sometimes the world tells us that to be a man means relying on no one but yourself, don’t ask for help, don’t be vulnerable. Men don’t talk about love. Real men don’t cry and things like that.

That is just not true. It is not the pattern of Jesus. We can share our needs with our families and friends, but most importantly, we need to share our needs with God.

When we feel frustrated in life, we know that God understands, God is with us, and God is for us. God raised Jesus from the dead in victory over sin and all of life’s struggles.

Ask God, trust him, and he will help.

In all the change and uncertainty of life, God’s love remains constant. God’s love does not change. God’s love is perfect. God’s love is faithful and true. And God loves you.

Fathers, husbands, and men today, can you leave this place trusting that love in a new way today?

Let’s pray:

Loving and gracious God our Father.

You are our creator, and we are your children, made in your image and likeness.

We praise you today because you are loving and good.

You have shown your love for us in sacrificing your very self.

While we were sinners set against you, you died for us.

God, we are thankful.

And you have called us to reflect this love, this love that is your very being.

Father, teach us how we can do this better.

Many of us feel like we are not all that good at it.

And in a changing world, many of us desire to follow our ways, but the way does not seem all that clear.

God, give us wisdom.

Encourage our hearts: Remind us that there is nothing in all creation that can separate us from the love you have for us.

Show us how we can love our families better.

Thank you so much for all the examples of fathers we have around us. Thank you for the sacrifices they have made, the lessons they have taught, and the fun we have had with them. May we cherish these gifts among us today.

We pray that today the fathers, husbands, and men of this church would know your love in a new way, be able to trust that love, and live that out.

Give us your Spirit, for we know you are faithful.

Amen.

The Risk of Becoming A Father: A Theo-Poetic Reflection

This is a reflection I wrote back in 2011, when my first son, Rowan, was born. It is, as I call it, a “theo-poetic” reflection, as I could not help but think about the grandness of this event as connected with faith in God.

Some would question whether fatherhood is a valid impetus for religious reflection. What do the two have to do with each other? I am of the opinion that even an atheist, when gripped with the beauty of life’s greatest moments ultimately resort to religious-like vocabulary: words of transcendence like “sublime” or even, “sacred.” There is a reason why the Hebrew prophets were not scientists or philosophers – those who think the mysteries of life can be objectified, scrutinized, and exhausted, those that naively hold that thought begins in doubt and ends in certainty rather than beginning and ending in wonder. Rather, all of the prophets were poets.

Many know their fathers as appearing cold and silent, perpetually poker-faced. After my son was born, my wife turned to me wondering why I did not cry at the sight of my son. I said that I did not know. I almost felt ashamed that I did not. Could I be that emotionless? However, as I reflect on this, and many of the powerful moments of my life, I have found that there are, for me, moments so profound that their magnitude invokes such a complex polyphony of emotions, our bodies do not know how to express one where our minds are wrestling with many. It is not that men are emotionless or emotionally shallow (as some have said), it is, I think, that sometimes we are so complicated, no one expression of emotion does justice. Thus, we appear reductionistically simple.

For this reason the Christian scriptures were not written as pure historical reports, logical propositions, and empirical data – objective yet dry, stale, and irrelevant – but rather as narratives, poetry, proverbs, and epistles – subjective, personal, and thus, real and relevant. Poetry is the enemy of science, as science accuses poetry of un-realism, yet it is poetry that seems to come to grip with what reality is for the human experience more than science. In French, the same word is shared for an account of history and a story, l’histoire, as it is understood that in order to communicate the flavor of life’s memories accurately, one must ironically use the metaphor, forsaking the demands of the factual in order to fulfill it and employing the rich meanings found typically in fiction. The wondrous thing about poetic reflection is that it is the attempt to wrestle into words the things that matter most to us, yet render us silent and speechless.

It is a strange wordless feeling becoming a father. Watching my wife’s pregnancy was just that: watching, a position that intrinsically predisposes a father to a sense of aloofness. Another’s pregnancy, for all its power to produce the sense of maternity, is no process to prepare for one’s own paternity: no inherent connection is formed between father and fetus, no nesting instinct clicks on automatically. A guy does not spend his childhood unwittingly rehearsing for childcare with his toys and their many nursery related accessories. Compared to the astounding ability to produce life from within oneself, to shift seamlessly and intrinsically into a parental-consciousness, men are left feeling as the “weaker sex.” Fatherhood, at least in its initial impulse, far from its place in perceived male headship, subverts the great chains of social hierarchy – hierarchy with all its promise of strength and security – that we as men wish to remain unthreatened.

I take Meagan in to be induced on the evening of Good Friday. We stay the night for observation. I don’t sleep. I can’t sleep: part anticipation part the stiff hospital chair-bed-thing is not actually suitable for sleeping.

Then the labor happens in the morning, Easter Saturday, April 23. Trumpets from heaven might have well of blasted: all the signs were there, all of it expected, however, an urgency sweeps over you that makes you feel you were never ready for what is to come. All preparations feel illusory and inadequate. It is the eschaton of my life, as I know it.

Moments become eternal as memory fragments into snap-shots that somehow also bleed together like a long exposure photograph: At the hospital, Cervidil administered, epidural, lunch from the Hospital’s Subway, contractions set in, the movie Ben-Hur plays in the background, cervix is fully dilated and ready to push. I look at my watch, its 4:25. Ben-Hur is at the chariot race scene. I hold Meagan’s hand. I hold her leg. Meagan’s mother, on the other side, does the same. Breathe. Push. Pause. Breathe. Push. Pause. I see the head.

I am not going to lie, it is gross. Life in it’s most raw forms, we often find disgusting; without all our prim and proper adornments to shield ourselves from the overwhelmingly messy purity that life is, we find it scary before we can properly appreciate it as sacred.

A haze of helplessness, ignorance, and anxiety from watching my wife have contractions, have pain, have labor, have something I have never witnessed before and can never understand, leaves me unsure of what is going on, what I should be doing, what I could even do at all. Men are supposed to “fix things.” I don’t know what to do. I say, “Good job,” as if I am the expert, as if I am not feeling awkwardly pathetic.

It all comes to the pivotal moment I see the little body and the loud cries begin. The sur-reality of labor splits sunder by the sharpness of the in-breaking reality of delivery. Adventus at 4:57.

The image behind the shadowy ultra-sound phantasms and amorphous movements within the belly manifests itself for the first time in one tiny distinct form: the crying naked body of a tiny baby boy. The tohu-wa-bohu of childlessness break by the bara of conception, that leads to the badal and miqveh of pregnancy, and culminates in the final barak of birth.

I give my wife a kiss, no longer simply between two lovers, but from the father to the mother of our child. A mature love is affirmed, love that culminated in new live, a new journey: our family. I hold my wife, my wife holds the baby, the baby holds my hand. Bone of my bone holding flesh of my flesh: we are three, yet, in love, we are one.

We named him Rowan Albert Boersma, Albert after my dad, John Albert Boersma. However, I was so tired after the birth that when I called my family to tell them the news, I told them the wrong name! It was the most pleasant point of exhaustion, I’ve ever felt!

I take my son in my arms and I look at him, and he opens his eyes and stares at me. Some refer to a religious experience as an “I-Thou” encounter, the finite “I” encountering God’s absolute “Thou.” The presence of the infinite being produces a sense of being infinitesimal, under the weight of the wonder of that which is Wholly Other. To hold my son for the first time is an similarly unspeakable feeling, apophatic yet oddly inverse: I feel like the thou, staring down at this being that is in my “image and likeness,” this person that is utterly dependent on my providence: so small, so fragile, so vulnerable, so innocent, but above all else, just so. With all that I am, I pronounce blessing on this being: I see him as “very good.” His finger reaches out and touches my finger in Michelangelo-esque sublimity.

As I sense myself as the Thou, the child becomes the I. And thus, I see myself in something other than me. In doing so, eye to eye, I sees I, self-hood is seen in another and otherness in self, an infinite reciprocal circle of identity and alterity. A type of self-transcendence occurs. The I-Thou reverses as I stand before a new tiny Thou. All senses of deity, the feeling of being bigger than you have ever been, paradoxically permeates with the sense of being smaller than you ever have been, feeling the full weight of fatherhood, the magnitude of responsibility, and the fear of innumerable potentialities of failure. The future in all its awesome potentiality presents itself, simultaneously dazzling as dangerous.

In holding that child for the first time, with the instantaneous love, you feel that you are more sure about what is right in the world than ever before, yet at the same time the most unsure. With love, an kenotic agape occurs as someone other than yourself becomes the measure of your essence. As you love this little someone, you see yourself in them, and your own idenity as a loving person becomes bound to them, covenantally. You bind your self-hood to something other than yourself, freely allowing yourself to be taken hostage to this someone that you know has the uncontrollable judgment to pronounce you a success or a failure in your task of loving, in your ability to be loving. The certainty in love appears also as the greatest risk. For those that define masculinity as a man’s self-sufficiency, power, and ability, fatherhood appears as a threat-to more than a fulfillment-of manhood.

Is this what God felt like as he beheld Adam? Is this what the Father felt as he looked down upon Christ lying in a manger? Through the divine tzimtzum, is this the risk of God’s essence as love entails as he constantly proclaims to his children, those other than himself yet from himself? Is this the mystery of God’s promise and proclamation to all humans, when he says, “I am love; I created you from love; I love you; I will always love you”? Is it in the finite response of gratitude for God’s love that God’s infinity is realized? Did God, as a being whose supreme ontological predicate is love, risk his very deity in the act of creating humans? It is only when every “knee bows and tongue confesses” the Spirit’s love, Christ’s lordship, and the Father’s paternity that God will truly be “all in all.” The marvel of God’s sovereignty is his willful vulnerability.

How can God be vulnerable? In Greek mythology, Cronus the Titan devours his children so that none can challenge his sovereignty. Zeus the all powerful, Cronus’ son, slays his father, only to become an absent uncaring father himself to myriads of bastard children of the women he seduced. He, the “father” of all gods, is a god that intervenes to win wars for his subjects – wielding the symbol of his power: the lighting bolt – only for the profit of more temples, more worship, more reputation, more fear of his might. The gods of the Greeks were defined as timeless, impassible, unchangeable, omnipotent and omniscient. And because of this, the Greeks logically concluded, in all their metaphysical sophistication, that the gods do not care about us. They must not care, or else they would not be gods! To care is to be weak. This is what the world conceives of as divinity: power and control.

Some wonder why an infinite deity would choose to identify himself as gendered and allow himself to be named by his people as “our father” (although there are many parts of scripture, I should point out, where God is depicted as motherly too), yet everywhere in our world we see absent fathers – people, perhaps, afraid of the risk of love – broken homes, abandonment, even abuse. And yet in our darkest moments something, someone, beyond all our experience, beyond all notions of how the world is, pierces the veil of despair and shines through in glorious consolation: God as love appears as the one that never abandons, always keeps his promises, always protects, is always proud, is always daring to love.

The God who identifies himself with the stories retold by the community that claims their brother is Christ is a God that we profess does nothing like what a god is expected to do: he comes into history, changes himself into a sacrifice, suffers with us, becomes weak and helpless choosing powerlessness over violence, chooses compassion over wrath, and even is said to have become the very thing God is not: the misery of sin and death. Though the vile yet beautiful cross – the symbol of the Christian God’s awesome ability – all this was done to say to all the fatherless: to all victims those crying out for rescuing, to all the abandoned that will never understand themselves as being worthy of a father’s proud smile. All this to say to all people: you have a father! Daddy loves you. He is proud of you. He will rescue you. He is never going to leave you.

Indeed, no psychological projection, no philosophical system, no misguided mythology constructed by human minds could invent the notion that a God would choose to use masculine language to define his magnificent characteristics yet fundamentally in his very essence, in his very being and becoming, be something so unbecoming of the impassible power and sovereign invulnerability of our notion of “male” deity, that is, the unfathomable and ineffable reality that God is love.

Hearing my crying child, holding him for the first time, and not knowing what to do to end the crying is an absolutely terrifying experience. Something so small renders someone so much older, bigger, and more capable that itself, ultimately incapable: omnipotence dissolves into omni-incompetence. However, he calms down and sleeps sweetly, and I pause to take in the strange soothing fragrance of a new born baby at peace on my chest, his soft head against my cheek. We both rest, I in pride and Rowan in purity. I think to myself that this is how God must have felt on the seventh day. Shalom, the peace that all existence strives for, engulfs us.

I use the blue musical teddy bear to comfort him, the same one my father used to comfort me. Now I understand what my parents felt, and I regret every moment that I ever took their love for granted. My father has passed away, my mother also, yet I am here. I say, “Daddy is here. Daddy is never going to leave you.” A generation passes, a generation comes, and yet in the flux of life’s frailty, for all its uncertainty, love is what remains eternally and assuredly the same. Death is no competitor to the renewing power of life through love. The “risk” of becoming a father, love’s risk of being inadequate, vulnerable, and the potentially a failure, in turn, is then what becomes illusory, dissolving into epiphany, as love’s jeopardy becomes life’s victory, as love demonstrates itself as the essence of immortality, as love demonstrates that love “always protects, always trusts, always hopes, never ends and never fails.”