Category: Uncategorized

We’ve Missed The Point: Ascension and the Meaning of the Bible

Preached at Lawrencetown United Baptist Church, Ascension, 2024

Then he said to them, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you—that everything written about me in the law of Moses, the prophets, and the Psalms must be fulfilled.” Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures, and he said to them, “Thus it is written, that the Messiah is to suffer and to rise from the dead on the third day and that repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things. And see, I am sending upon you what my Father promised, so stay here in the city until you have been clothed with power from on high.” Then he led them out as far as Bethany, and, lifting up his hands, he blessed them. While he was blessing them, he withdrew from them and was carried up into heaven. And they worshiped him and returned to Jerusalem with great joy, and they were continually in the temple blessing God. (Luke 24:44-53, NRSV)

There was a movie that came out a few years ago called The Book of Eli. It starred two great actors, Denzel Washington and Gary Oldman. The movie takes place in a time when the world has been destroyed in an apocalyptic event, possibly a nuclear war. The survivors believed that the old ways in some way caused these events, so in anger, they burned all books, particularly religious books.

Many years later, the world is dark and chaotic, made up of brutal tribes. Only a few elderly people know how to read, let alone know about religion and books like the Bible.

A man named Eli (played by Washington) emerges, walking along the road to somewhere with the last Bible in existence. And he believes he is on a mission from God to bring it to a place God has shown him.

As he passes through one town amongst the desolate wastes, a warlord named Carnegie (played by Oldman) learns that he has the last Bible. He, too, is an old survivor. He remembers, as a boy, seeing televangelists on TV and how much power they had by invoking that they were speaking words from God himself. He remembers his own mother, a struggling single mother, desperate, sending money to a televangelist, money she did not have, and telling him that faith is the most powerful force out there.

Carnegie wants this power: the power to control desperate people. He realizes that the power to speak on behalf of God could allow him to rule unquestioned.

So, he sets out to get this last Bible from Eli.

Two Ways of Using the Bible

The movie sets up a stark contrast between Eli and Carnegie. Both want to use the Bible but for two very different purposes.

In fact, there is a scene in the movie where Eli is sitting there reading the Bible in an inn, and a woman comes to him, sent by Carnegie (she is his slave), and she tries to seduce him in order to get this prized possession.

Instead of taking her up on that offer or condemning her, he turns and has compassion. He sees in her despair over life. So, he encourages her to be thankful and to cherish her life as something valuable, a gift. The woman is confused and admits she doesn’t think that her life is worth anything. But she asks, how do I do that?

So Eli takes her hands and folds them and tells her there is this old practice called prayer, which is something you can do to be thankful and have hope. He teaches her to recite these ancient words: “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven…” He tells her about the words of the book he reads, that these words are the words of hope and love.

Instead of condemning her or using her, he uses the Bible to give her hope.

Now, in one of the more entertaining but theologically unsound aspects of the movie, when Carnegie comes after Eli, we realize that Eli has God’s supernatural protection. What kind of divine protection, you ask? Good question: Eli has supernatural gun-fighting skills, slaying a small army’s worth of Carnegie’s men when they come at him. I feel like the writers of this movie may have missed a passage or two from the New Testament.

Or, maybe this is trying to allude back to someone like Samson in the Old Testament. Maybe I may have missed one of the lesser-known spiritual gifts in the New Testament. Or, maybe this is just a movie made by Hollywood, and we all know guns and explosions sell tickets.

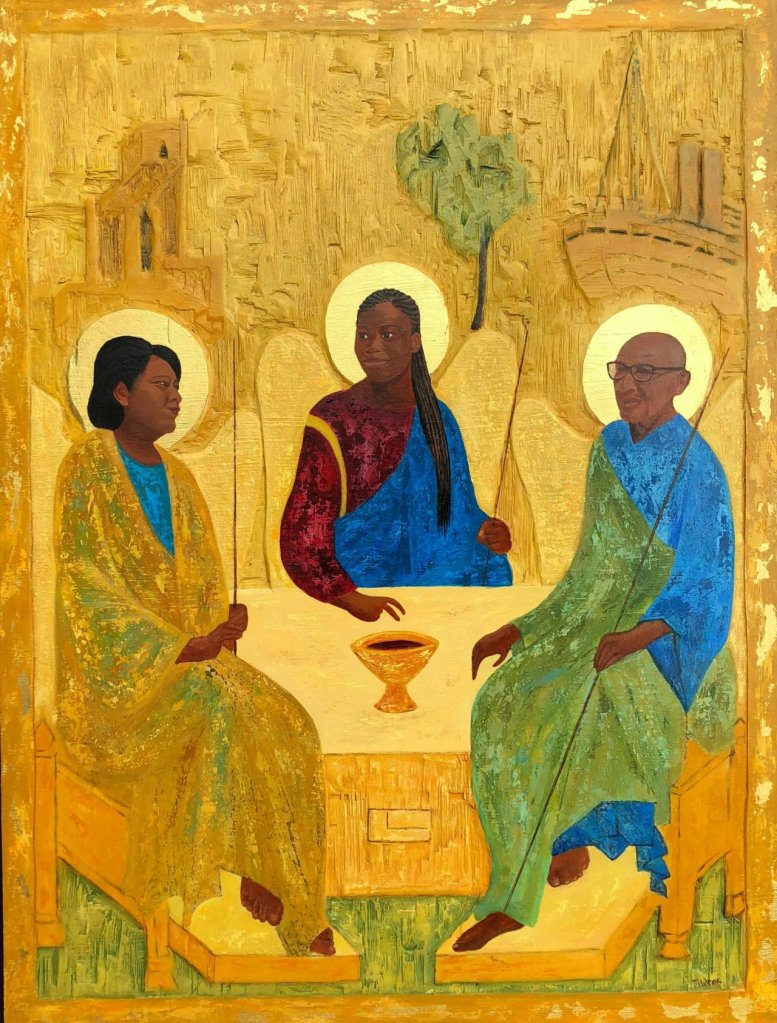

Be that as it may, the movie is not perfect, but it draws attention to an aspect of this narrative we read today: The resurrected Jesus, just before he ascends to the Father in victory and vindication, opens the eyes of the disciples and they see how the scriptures are fulfilled in him, in his cross and resurrection, fulfilled in his way.

This is something Luke is trying to impress on us from chapter one of his Gospel: The Bible does not make sense without seeing it through Jesus and his love and hope for the least of this world.

You see, Eli and Carnegie represent two ways of thinking about faith and the Bible. Both want to use the Bible, and both have an idea of the authority of God, but their approaches couldn’t get any more different.

One wants to use the Bible for power, control, to bring himself closer to God over others. There are folks in the Gospel that want to do this, whether it is the Pharisees or even Jesus’ disciples. Jesus talked about the kingdom of heaven, and his disciples, James and John, immediately saw Jesus as a pathway to power and status. That is not what Jesus was about. Jesus said, “I came not to be served but to serve and to give my life as a ransom for many.” He also said, “If you want to be my disciples, you have to take up your cross and follow me.”

So, there is also the way Eli uses the Bible: to use the Bible to bring others closer to God, bring hope, compassion, and encouragement. You see that happen in Luke’s Gospel: Jesus heals on the Sabbath; Jesus eats with tax collectors and sinners; Jesus proclaims justice and liberation.

Again, both want to use the Bible, and so, in the loosest possible sense of the term, both want to be “biblical,” but I think we all know that just because someone can quote the Bible does not actually mean they are using the Bible for what it was meant for.

One uses the Bible in a way that points to who Jesus is and what Jesus was about. The other does not.

This is a part of the epiphany the disciples had to learn on that day all those years ago, and it is what our eyes must be awoken to today if we are going to be faithful Christians of our ascended Lord today.

Ascension and the Lesson Jesus Wanted His Disciples to Know

So, it was Ascension this week. If you don’t know what Ascension is, it is the day of the year that traditionally Christians remember Jesus being taken up to heaven after he was resurrected, celebrated 40 days after Easter.

For some reason, we don’t give gifts. We don’t have a turkey. We don’t even eat chocolate eggs (However, some of us still have chocolate eggs hidden from our kids from Easter, mind you). For some, the day of Ascension comes and goes without us realizing it, usually because it coincides with Mother’s Day (Happy Mother’s Day, by the way). Despite it being the conclusion of the Gospels, the end of Jesus’ earthly ministry, it just never seemed to have caught on the way Christmas, the beginning of the Gospels, did. Nevertheless, it is a day in the Christian calendar all the same and it is worth celebrating.

After the crucifixion and the resurrection, Jesus finally helps them see all that they did not understand but can now know in hindsight. He gives them new eyes to see and new ears to hear what is going on in the Bible.

Ascension is that pivotal point where Jesus brings his earthly ministry to a conclusion before going up to heaven and reigning as our mediator at the right hand of the Father, and it seems that Luke is keen to tell us several times here that Jesus explains how the scriptures are fulfilled in him.

We see this in the passage before, where two of Jesus’ disciples are walking on the road to Emmaus and the resurrected Jesus appears to them and walks with them, and they don’t know it is him. They lament how the prophet Jesus was killed. They were disappointed because they really thought he could have been the Messiah.

They thought that Jesus was going to rise up and kill the Romans, liberate the people, and restore the kingdom of God that way, with violence. So, obviously, the cross, the execution of Jesus at the hands of both the Romans and the religious leaders of Israel kind of kiboshed that.

Or did it?

Luke tells us that Jesus revealed himself to them and explained to them along the road to Emmaus how the whole of the Old Testament scriptures pointed to him, to him going to the cross and rising again.

The cross, its brutality and shame, its lowliness and powerlessness—it did not disprove Jesus as the Messiah; it fulfilled it. To us church folk two thousand years later, we don’t consider just how contradictory this probably sounded: A crucified messiah was an oxymoron, like “jumbo-shrimp.”

The law says that anyone who hangs on a tree is cursed. Surely, God cannot be with a man who dies a death like that. Surely, God would protect a true Son of God from such evil. And surely, no one who claimed equality with God could be anything other than a blasphemer if this happened to them. That was what the assumption was.

But as Jesus went to the cross, as all the Gospel writers tell in different ways, Jesus was speaking the words of the Psalms, embodying the patterns the prophets lived, fulfilling in his very body what the Word of God is truly about.

“Why have you forsaken me?” That is a line from David in Psalm 22, who wondered where God was to protect him and the innocent righteous. And yet, to have Jesus speak these words, who claimed to be at one with God, here was God identifying in solidarity with all those who feel forgotten by God.

The disciples could not get their heads around this. This was not supposed to happen in their minds. He could not be the messiah if this happened.

Yet, when you look at the narratives of the Old Testament, you see the truth of the cross. You see Joseph, whose honestly lands him in prison. You see David, whose anointing as king means he spent his early years hunted and hated. You see Job, who endures pain and tragedy to show that he loves God for no benefit. You see Jeremiah, who is branded a traitor, shoved down a well to die, and exiled, all for speaking God’s words.

You see the truth of the cross in the Old Testament: that the good, the just, and the innocent often suffer in this world and are attacked and scorned by the powers of sin.

This leads so many of us to ask: Is evil winning in this world? Is there anything we can do? Is love and hope in vain?

One writer put it this way: Biblical faith makes us realize that if you have not loved, you have not fully lived, but if you love fully, you will probably end up dying for it.

That is what happened to Jesus. Jesus came proclaiming the kingdom of heaven, that the first will be last and the last will be first, that God is here for the humble and the humiliated, the pure and the peacemaker, the merciful and those in mourning.

Jesus came preaching that the law is summarized in love, and the powers and the principalities felt threatened and killed him for it. Jesus’ own people, the leaders of his own religion, saw what he was saying as blasphemous. Yet even in the execution of the cross, the worst evil the people could do to God’s messiah, Jesus is shown praying for them: “Father, forgive them; they know not what they do.”

The cross is the moment when the evil in the human heart and society shows its ugly head, and God chooses this moment to show us in Jesus the kind of God he is: A God willing to love us and die for us.

God loves us with his very best, even when we are at our very worst.

Evil did not have the final say over Jesus that day, nor does it have the final say over history, nor does it have the final say over you, your life, your future.

Jesus rose from the grave. Death, the devil, the powers of disobedience and despair, oppression, and bigotry were overthrown by victorious love.

Today is Ascension, and Ascension means who Jesus is and where Jesus is now, which means that love and not hate are in control of this world.

Grace, not domination, is what wins in the end.

Forgiveness, not fear, is what prevails.

That is the point of the Bible.

From creation to covenant, from exodus to exile, from tabernacle to temple, from Moses, the judges, the kings, and the prophets, the whole Old Testament was preparing God’s people for Jesus. All its figures, its imagery, its laws, its longing, all were anticipations of Jesus.

Jesus is who the whole of the scriptures, the law, and the prophets have been longing for.

Putting it this way says something about what the Bible is all about that we need to remember in this age so badly.

It is not merely that some of it points to Jesus. Jesus insists that it all points to him that Jesus’ way fulfills the deepest concerns about what the Bible seeks to teach.

We Have Missed the Point

It is sad to say this, but we Christians have not been particularly good at keeping this in mind. We so often lose the plot of the Bible and use it in ways that do not fit its purpose of pointing to Jesus and Jesus’ way.

Let me give you some examples:

My mom, bless her soul, had a book she read when I was little. I’d say she read it religiously, but that pun might be too on the nose. It was called the Maker’s Diet. Some authors combed through the Bible, arguing that if you want to live a long and healthy life, all you need to do is follow the Bible’s God-given recipe for healthy eating. Now, there is obvious wisdom to the dietary laws of the Old Testament in its own day and age – I am not disputing that – sure, these laws were to aid in maintaining the health of Israel, and certainly, God wants us to be healthy today, but the idea we could sift those laws out of the ancient world and drop them into our own. The purpose of the Bible isn’t a diet book.

When I was in high school, a book called “The Bible Code” came out. Do you remember the Bible Code? Some believed that since the Bible is divine revelation, there are obviously hidden messages and prophecies in it, sort of like how people believed that if you played a rock band’s LP in reverse back in the ’60s, you hear a secret message. Well, the Bible Code took all the letters of the Bible, and lined them up in a long ribbon and searched every other letter or every fifth letter and things like that, and lo and behold, some of the search results came up with things like “JFK, plot” or “Japan, bomb” or things like that. This was a sensation that became a best-seller, but unsurprisingly, when others found similar results from other long books like Moby Dick or War and Peace, the sales kind of tanked. Again, that is kind of a silly example, but I still know people who come to the Bible and treat it more like a crystal ball or, in particular, the Book of Revelation, some kind of mystical code to crack. That isn’t the point of the Bible.

Again, those are silly, more short-lived examples, but Christians throughout church history have come to the Bible to get the fast answers on a lot of subjects rather than discerning difficult matters with the wisdom the whole of the Bible is trying to instill.

People in the 1500s believed you could teach science right out of the Bible, and for them, the Bible clearly taught that the sun revolved around the earth. Then, a guy named Copernicus and his student Galileo came along, and it has been a bit messy between science and faith ever since. However, the point of the Bible is not science; it is an ancient text written before people had science. It does not tell us much about the what or how of nature, but it tells us why and, more importantly, who. Look at the references to Genesis 1 in the New Testament—passages like “In the beginning… was the Word”—and you realize that if you were to ask what the doctrine of creation the Apostles had, they would have answered, “It’s Jesus.”

For centuries, Christians believed that you could build a system of government using the Bible and that, of course, it was a monarchy or possibly a holy empire where the leader had unquestioned divine-ordained authority. But then religious dissenters came around, like Baptists and others, and said maybe a wise way to do government is to have leaders accountable to the vote of the people. Maybe if Jesus is king, we need to be a bit suspicious of giving anyone god-like authority.

Of course, the examples can get a whole lot darker from there.

Some folks came to the Bible thinking they found a timeless way to run their households, and the result was centuries of slavery and subservience of women, completely ignoring the context of a lot of these passages. If you have ever wrestled with those passages, you have to ask yourself: if the point of the Bible is Jesus giving up his power to liberate others from sin and injustice, it just does not make a lot of sense that we could use this passages today to control and limit others. That is not the point of the Bible.

When settlers came to this land centuries ago, they saw themselves as just as the Israelites entering a new promised land; the only problem with that is that this allowed them to treat the indigenous peoples of this land similar to how the Israelites responded to the Canaanites. In the name of saving people’s souls, Christians oppressed indigenous bodies. In the name of getting people to heaven, Christians did the opposite of the ways of the kingdom of heaven.

And if you read the reasons why people did these things, as I have studied, you will surely find passages quoted with pious intentions. That is a scary thing. It is a frightening reminder that the best of us is capable of terrible things when we lose sight of the center of Scripture.

They did these things because they failed to ask themselves that if the Bible is God’s word, how would Jesus, the word of God in the flesh, want these words to be spoken? How did Jesus live these words for us to follow?

Whether it is the smooth manipulative messages of televangelists, the crazy conjectures of conspiracy theorists, the justifications of war and corruption by world leaders, or the bigotry of some bible thumpers, we know that we are terribly prone to using the Bible in ways that don’t point to Jesus.

In fact, Jesus warns about this in his own day. When he speaks with Pharisees in John’s Gospel, in chapter 5, he says this: “You search the scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life, and it is they that testify on my behalf. Yet you refuse to come to me to have life.”

Jesus is talking to some religious people who know their Bibles really well, but they don’t seem all that gracious and loving with it, and since they are refusing to read the scriptures through Jesus, culminating in Jesus, they have failed to grasp its most important message: the message of true life.

Paul does something similar in 2 Cor. 4: “We have renounced the shameful, underhanded ways; we refuse to practice cunning or to falsify God’s word, but by the open statement of the truth we commend ourselves to the conscience of everyone in the sight of God.”

Notice what Paul is saying there. He is saying that there are folks who, by the very way, are using the scriptures, using the message of the Gospel, using it for personal gain and power and manipulation; Paul says they have falsified God’s word. Sure, they might be able to quote the Bible, but if they aren’t doing it in the way Jesus would say it, then it is not the words of Jesus. Simple as that.

Perhaps you have had a discussion like this with someone. Somehow, the conversation turns to talking about a serious topic, and instead of listening and appreciating how complicated a problem can be, the person just turns and says, “The Bible clearly says,” end of story. Thoughtfulness need not apply.

Sometimes, I have literally heard people say, “I’d love to be more loving or gracious on this matter, but the Bible won’t let me.” Yet, the law of love is the rule Jesus tells us to measure what law applies and which ones do not. Every Gospel, as well as Paul and James, all report this. I have news for you. If the Bible is preventing you from being more loving, you are reading it wrong.

Usually, when I have those discussions, I end up saying to myself, “Why didn’t we just keep talking about the weather or how our local sports team was doing? Why did I have to open my give mouth?”

We, Disciples, Must Be Different

And yet, I so deeply believe that if we want to follow Jesus, if we care about the Bible, we must study it with the care that it deserves. This does not mean we all have to be academics, although that is what I have been called to, and I try to serve in teaching as best I can. For many of us, it simply means we have to take the time to wrestle and contemplate who Jesus is and what his will is with all the wisdom we have available to us.

That might sound like a tall order, but the consequence of failing to live Scripture out in a way that points to Jesus is one tragic display all around us.

I have realized that if you want to justify pride and power, privilege and prejudice, if you want to condone violence and hatred or reinforce apathy and inaction, you can go to the Bible and cobble together proof texts here and there until you have a surprising case for whatever you want.

C. S. Lewis, the great Christian thinker and novelist, wrote this in a letter:

“It is Christ Himself, not the Bible, who is the true word of God. The Bible read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers, will bring us to Him. We must not use the Bible as a sort of encyclopedia out of which texts can be taken for use as weapons.”

Today, in terrible ways, we are seeing the Bible used as a weapon. Make no mistake: hundreds of thousands of people have died this year because people have justified their violence with Bible verses.

And rather than give up on the Bible, on faith, or the church, we who are Jesus’ disciples, his students, must show the world otherwise.

You see these scriptures, these documents that Christians in time collected into 66 books, two testaments, bound and printed. These scriptures are a remarkable tool for the church to stay on the right path and understand who Jesus is. These scriptures are, as Paul says in 2 Timothy, “God-breathed,” animated with the Spirit of life who is seeking to transform every soul into the fullness of life with God.

But never forget that these words, these pages, don’t make sense and, in fact, can do profound damage when we stop reading them for how they point to a God that loves humanity, every human being, with a love that forgives every sin, knows every pain, a love that is willing to die sin’s death and yet heal every wound, a love that refuses to stop until God is all in all.

If we don’t listen for that voice speaking, that love breathing through the pages of the Scriptures, we have missed the point.

And so, Lawrencetown Baptist Church, on this Ascension Sunday, may you know that in Jesus Christ, his cross, and resurrection, the scriptures have been fulfilled.

May your eyes be opened, and may you hear afresh how in Jesus Christ we have forgiveness of sins, the fullness of love and truth and grace.

May we be witnesses of this good news, the Gospel that is for all people: comfort for the discouraged, liberation for the oppressed, hope for this broken world.

May we, by God’s help, have the faith to take up our crosses and the courage to live these words out this week.

Let’s pray,

Almighty and everlasting God

you raised our Lord Jesus Christ

to your right hand on high.

As we rejoice in the culmination of Jesus’ earthly ministry,

Imprint your word upon our hearts and minds so that we more every day be conformed to the image of your Son Jesus Christ.

Teach us to love like him. Teach us to be truthful like him.

Teach God, even though we so often forget.

Ready us for Pentecost and fill us with his Spirit,

that we may go into all the world

and faithfully proclaim the Gospel and welcome your coming kingdom.

We ask through Jesus Christ our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, forever and ever. Amen.

“Our Crosses Are So Shiny”: Christian Faith and the Seduction of Power and Privilege

Preached at Billtown Baptist Church, Sunday, February 25, 2024.

Scripture reading: Mark 10:17-45 NRSV

Introduction: The Life of Clarence Jordan

There was a Baptist pastor named Clarence Jordan. Has anyone heard of him? He was born in 1912, and he died in 1969. Jordan was from Georgia (By the way, a fun fact about me is that my grandmother, my Father’s mother, hailed from Georgia). He was born into wealth and privilege, but at an early age, he felt a profound call to help others. He did his education in agriculture in 1933, so this is during the great depression, and he did this because he believed he could help farmers develop more scientific ways of farming at a time when poverty was widespread across the land. But as he was doing this, he became increasingly convinced that his calling was in ministry. He saw poverty as just as much an economic problem as a spiritual one. So, he did a master’s as well as a Ph.D. in New Testament. Challenged by his in-depth studies of the New Testament, he came to realize that the teachings of Jesus were simply incompatible with racial segregation that was not only tolerated in his community but also taught in the churches. God put it on his heart to do something about this.

In 1942, Jordan and his wife, along with a couple of former missionaries, bought a 440-acre chunk of land. Jordan used the savings he had received from his affluent background to do this. They called the farm “Koinonia,” after the Greek word in the New Testament for the community, and they founded this community on the refusal of racism, violence, and greed. They opened up their community in hospitality to anyone who might come who needed a place to stay, in particular, black people who were fleeing abuse. There, at the farm, people could live for a time, learn how to work the land, learn skills like how to fix and build things and leave when they were back on their feet.

For almost ten years, Koinonia did its work, living in a radical community largely unnoticed by those around it. However, when the civil rights campaigns began in the 50s and 60s, Koinonia became a target. The community was a church part of the Southern Baptist Convention, but it was disfellowshipped for its “communist race-mixing.” However, as it has now been brought to light, many people in the South, many Baptists included, were members of the KKK at the time, and these individuals saw what Jordan was doing and saw his community as a threat to God’s order of things.

In fact, some tried to organize a boycott so that the farm would no longer receive oil in the winter. The oil delivery people were threatened as they confessed to Jordan. “I could lose my business if my other customers boycott me for supplying you,” one man said. Jordan would respond back, “You know we have children on the farm. Do you want people to freeze during the winter?” After the man protested, Jordan put it this way: “The choice is clear: lose your business or lose your soul.” He had a no-nonsense way of putting things.

However, that man had reason to fear. As tensions escalated, so did the violence. The community experienced several bombings, and even members of the farm were fired upon folks from the adjacent farm. The buildings of Koinonia farm were bullet-ridden from folks firing at the buildings, trying to intimidate those inside.

By the way, if we somehow believe that terrorism is a problem for other religions and not us, go ahead and google the history of “Christian terrorist groups.” You might be, unfortunately, surprised by what some people have justified in the name of Jesus.

In dire need, Clarence Jordan appealed to his brother, Robert Jordan, a lawyer who later went on to become a senator and judge. Clarence Jordan recorded their conversation:

“Clarence, I can’t do that. You know I have my political aspirations. Why, if I represent you, I might lose my job, my house, everything I got.”

“We might lose everything too, Bob.”

“It’s different for you.” (As if to say, you are one of those weird religious types that actually takes this stuff seriously).

“Why is it different? I can remember, it seems to me, that you and I joined the church the same Sunday as boys. I expect that when we came forward, the preacher asked me the same question he did you. He asked me, “Do you accept Jesus as your lord and savior.” And I said, “Yes. What did you say?”

“I follow Jesus, Clarence, to a point.”

“Could that point by any chance be, Bob, the cross?”

“That’s right. I follow him to the cross, but not on the cross. I am not getting myself crucified.

“Then I don’t believe you’re a disciple. You’re an admirer of Jesus but not a disciple of his. I think you ought to go back to the church you belong to and tell them that you’re an admirer, not a disciple.”

“Well, now, if everyone who felt like I did do that, we wouldn’t have a church, would we?”

“The question,” Clarence said, “is ‘Do you have a church then?’”

Would that even be a church at all?

Eventually, Jordan had to close down his farm and leave the area. He eventually came to be the mentor of a young Baptist politician named Jimmy Carter (if you have not heard of Clarence Jordan, I hope you have heard of Jimmy Carter). Carter went on to become the governor of Georgia and helped dismantle segregation. He then went on to become President, and after that, he formed a charity, inspired by Clarence Jordan’s witness to housing the less fortunate, called Habitat for Humanity.

The Difference between Merely Believing in Jesus and Taking Up the Cross

So, if you have been tracking with us in this series, we have been reflecting on the life of Christ. We have been going through his teachings and major ideas about who he is.

The last time I spoke, I noted that there were folks today who tend to think the apostles invented Jesus as a divine messiah as time went on. But as I said, when you look at some of the earliest stories about Jesus, some of the earliest writings of the Apostles, Jesus seems to be doing things that only God could do. While this was surely a mystery, something the Apostles admitted they did not fully understand, Christian thinkers have looked back at these narratives and suggested it looks like Jesus had two natures, that in all the ways God is God, Jesus is God, and in all the ways humans are human, Jesus is human, and that doctrinal rule is the best summary or encapsulation of what is going on in all these rich and multifaceted stories in the New Testament.

And so, Christians throughout history have insisted that Jesus is very human and very God and that this truth is essential to understanding God’s love and presence in our lives. It is a matter of what is called “orthodoxy,” meaning “right belief.”

Now, there is also a truth that Clarence Jordan’s life and experiences show us that gets to the core of what our passage today is trying to tell us, which suggests to us another layer or facet to this exercise we call “believing.” You see, understanding who Jesus is necessarily means changing how we live, and more than that, in particular, it confronts how we understand privilege, status, and power. However, this part of our convictions is much harder to measure. Some things can only be lived and shown.

It is one thing to believe in Jesus, quite another to live like Jesus.

It is one thing to believe all the right things. It is quite another to believe in the right way.

Or worse, we can actually use our sense of believing in Jesus as a means of getting power, staying in power, and staying comfortable.

To be a Christian means, as James and John show us, we must be aware that there are ways we can use believing in Jesus to get out of living the cross.

The Rich Young Ruler: Piety Masking Privilege

Our passage today begins with Jesus being approached by a rich ruler, who runs to meet Jesus and kneels down to him, asking, “Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” This question sets up the whole section, as we will see. Jesus is rightly skeptical. Nearly all in the ruling class at the time did so by exploiting and extorting the poor peasants, and to have this man come to Jesus acting this way looks like a display of theatrical flattery. “Why do you call me good?” Jesus inquires.

Jesus responds to his question, telling him to follow the commands of God, which the ruler proudly announces he has been following them just fine since his youth. That is doubtful. Then, Jesus hits him with a request: “If you want eternal life, sell everything you have, give it to the poor, and come and follow me.” The ruler could not do it. Apparently, he has been living out this holier-than-thou mentality, but that has really been a cover for greed, materialism, and exploitation, and Jesus sees right through it.

It is funny how we treat our sins as the ones that are easily excused while another’s sins are the real bad ones.

The disciples see this man leave dejected, and Peter turns to Jesus and says that they have left their homes and families to follow Jesus. To which Jesus responds, “Many who are first will be last, and the last will be first.”

That statement is one of Jesus’ most important teachings. It is really at the core of what his teaching on the kingdom of God is all about.

It seems this story that happens just before our passage today sets up a contrast between the disciples, who are poor but also, for the sake of following Jesus, give up home and family (and, as we know, eventually their lives) and a man that has power and wealth who cannot part with it, yet believes he is fully obedient to God.

It seems that for some, being a member of God’s people is a way of getting us off the hook for the really difficult stuff.

For some, being generally good and generally obedient is a way of getting off the hook for being radically and totally obedient.

It seems that this rich ruler has used his sense of faith and piety to make sure he stays first in this world. It is something we can all do. We can use our faith and our beliefs to reinforce and prop up our position in our communities and our jobs, to elevate ourselves, and to absolve us from doing the things God is challenging us to live: things like deep humility, radical justice, self-sacrificial love, etc.

James and John’s Request: Seeking Power through Jesus

So, Jesus continued on his way but started to talk about what was going to happen to him. Jesus knows that trouble is coming. He tells them that soon he is going to be betrayed. He is going to be arrested, tortured, and killed, all by the religious establishment and Rome, yet he tries to say to them, I will rise again.” Evil will not have the final say.

There is a saying by one theologian that goes like this: “At the core of the Christian faith is this paradox: it holds that if you do not love radically, you have not fully lived. However, if you do love radically, the world may end up killing you for it.” That is exactly what happened to Jesus, and here he is, trying to get his disciples to understand this.

After he tells them this, however, John and James, two brothers, come to Jesus with an unusual request. It sounds like they really only heard that last part about Jesus rising again in vindication and victory. They ask Jesus: when you come into your kingdom, can you make us your first and second in command?

And Jesus turns to them. Did you not just hear all that I said about what was going to happen to me? Do you still think my kingdom is about getting power?

Do you still think following me is about staying comfortable and not having to sacrifice status? Do you still not get it? He says, “You know the world has rulers,” not unlike the one Jesus just chatted with, “who lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you.” James and John try to exploit their connection to Jesus as a way of getting power and prominence over others. “Do you still not get what my kingdom is about?”

My kingdom, as Jesus says in Matthew 5, is for the poor in spirit, the meek and humble, those broken in mourning, those that hunger and thirst for justice, those who are merciful and pure in heart and peaceful, and those that hold to the truth and to justice even if it costs them.

My kingdom is for those who are last in this world, those who make themselves last, sacrificing wealth and status, and those who take up their cross and follow me. Do you still not get it?

Our Temptations to Power

Do we not get it still today? Sadly, this temptation of James and John’s does not go away in Christianity. We see this temptation again and again.

Whether it is the rise of Constantine a few centuries later, where Christianity turned from a marginalized, illegal religion to a culturally dominant religion enforced by the state, since then, Christians have been quite fond of feeling called by Christ to hold power, and this has set a pattern repeated in many Christian empires and nations thereafter.

Sadly, we can see many examples where Christianity became wedded with quests for power and wealth where Christians in the name of Jesus have done things that are categorically against Jesus’ way: the crusades, the Inquisition, colonization, segregation, etc.

Or, sadly, what we are seeing now in the United States, South of the border. To denounce American politics almost feels too easy some days, something best left to jokes around the office water cooler, but the reality is these things are deeply serious. Some of us feel like we just keep watching some TV drama that is so bizarre and brutal it doesn’t feel real, but it is.

Just this week, as more evidence regarding the women the former President has abused comes forward, more evidence that he paid off a porn star comes further to light, as well as his many fraudulent claims in his businesses, as well as his role in inciting insurrection—as all of this continues to mount—the former President held a rally to garner further Christian support. His words sent chills down my spine as he promised that support for him would be rewarded with him making Christians powerful and prominent in ways never seen in this country before. And these words were met with applause and amens and people shouting out, “Thank you, Jesus!”

Again, going after American politics feels like going after the low-hanging fruit, and I feel obliged to say that we in Canada have our own temptations. Who have we supported purely because of the carrots they dangle over our faces?

I would also say that it is not just an American problem. This week, I was invited to sign a letter to the major world Christian leaders as a Baptist theologian in response to the actions of the Russian orthodox church and its continued approval of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Patriarch of Moscow, Kirill, has called the war a divine mandate and has made statements that soldiers who die fighting are given special forgiveness in heaven. Thousands of innocent people are dying because, in the eyes of the Russian Orthodox Church, God desires some kind of restored Holy Russian Empire.

And so one cannot help but notice the irony that these things are being done by an ancient church tradition that has the word “Orthodox” in its title. It reiterates the fact that no form of Christian faith is immune to the seduction of power.

Now, we can do this politically, but this also happens in much more mundane ways.

For instance, when Meagan and I were first married, we attended a Pentecostal church in Newmarket, Ontario. It was a great mission-focused community. We were a part of a young adult’s bible study that grew. It was great. So many young adults started getting back into church as we read through the Bible and prayed for one another. People experienced a renewed sense of Christian community and discipleship.

However, things started going pear-shaped. One evening, one of the leaders of the group brought a DVD they loved on how to be “Blessed.” It was a DVD of a preacher who said that the Christian life is about trying to find God’s blessing, and God’s blessing means, clearly, “getting stuff.”

Meagan and I just looked at each other.

The preacher continued that if you are living in accordance with God’s ways, God blesses you with abundance; it is a sign of his approval of your life.

In fact, he then invited two testimonies of women in the congregation. One said that when they started being obedient, and by that, she meant that she started tithing money to the church, and she reported that God started blessing her husband’s business, and now they are millionaires (and you can, too, apparently). The other, much more modest in her testimony, said, “All I know is that when I give to God on a Sunday morning, then I go to the mall, it is like God opens all the sales at the mall for all things I need and desire. God is raining down his blessing on us.” I am not making this up.

At the end of the DVD, you know I had to pipe up. I said to that group leader, “So what do you do with a bible passage like the saying, ‘Blessed are the poor’ or the one just after it, ‘Woe to you who are rich.’”

The group leader looked at me skeptically and said, “Where is that in the Bible?”

I said, “It is in Luke chapter 6. It is the words of Jesus.”

I would like to tell you that my efforts to challenge that group were successful, but they were not. It ended up being a very disappointing experience for many of us who were in this group that originally set out to study God’s Word but ended up getting hijacked and ruined by all kinds of motives that drew us away from the things that mattered.

Now, some of us might not put it so obtusely as that preacher on that DVD put it, but the fact is there are so many ways we use our faith to stay comfortable. We can back our privilege with Bible verses when we want to, rather than taking up the difficult, costly way of the cross.

It can look like the repulsive theologies that Clarence Jordon confronted where overt racism was preached from the pulpit. It can look like the dirty politics and the mixing of church and state power that we are seeing in the world. It can look like the distorted theologies of blessing that say health and wealth are a sign of divine approval, which suggests that if you are poor, struggling, or sick, you are not loved by God. But it can look so many other ways, too, often covert and concealed, often cloaked with pious concerns.

These are all the ways we can make our faith about us rather than the way of Jesus, all the ways we can use the Bible to reinforce how we ought to come first.

We find ways of saying, “I deserve what I have, and I don’t need to share it. I don’t need to do this or that; I’m good enough. I don’t need to sacrifice for them; that’s their problem…I don’t need to take up the cross to have Jesus.”

The Ransom of the Cross: Jesus Becomes Last for Us

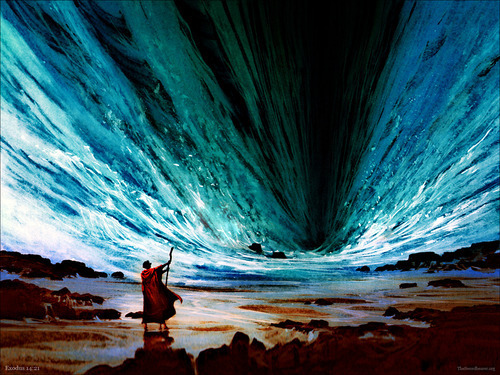

To this, Jesus makes his most explicit statement about the meaning of the cross: “For the Son of man came not to be served by to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

The language of ransom comes out of the book of Exodus, where God acts powerfully against Pharoah, a self-proclaimed god over an oppressive empire, ransoming God’s people out of slavery with signs and wonders.

Jesus is leading us out of slavery into a New Exodus. But what are we enslaved to? Mark’s Gospel makes that explicit: We are enslaved to the forces of darkness and the devil; we are enslaved to the fear of death, but to our own disobedience and despair. We are enslaved to our distorted religiosity just as much as we are to our political enemies.

These two are linked. God wants to liberate body and soul, not just one or the other, and that liberation comes together in things like our social status, where our spiritual pride and our material privilege are linked.

How does Jesus liberate us? By showing us God’s way. The cross is Jesus, the Son of God, the rightful king of Israel, who ought to live in a palace, who ought to command the legions and slay anyone who opposes him. This messiah did not come to be served by to serve, but by challenging oppression with his way, he knew it would end up with execution. It would mean the ultimate sacrifice.

To die by Roman execution would have meant the most humiliating and painful death a person could die: stripped naked, mocked, beaten, and pierced.

The cross is God himself becoming last in this world for us.

The cross is God becoming last in this world, and if we can humble ourselves, repent, and resolve to change by God’s grace and spirit if we live with an openness to the breaking in of God’s kingdom, we can know the promise of the resurrection. Jesus rose again.

The first will be last, and the last will be first.

We can’t have faith in Jesus without the cross.

Even then, Clarence Jordan had a saying. He looked at so much of the piety of the day, the comfortable ways of being Christian, and the tendencies to complain about how we don’t hold power as if we are now persecuted. He says this:

“Our crosses are so shiny, so polished, so respectable that to be impaled on one of them would seem to be a blessed experience.”

I will leave you with this thought: For many of us, our crosses are simply too shiny.

May we, in renewed ways daily, be challenged and convicted to take up Jesus’ cross. Amen.

A Different Kind of Christmas

Introduction: Which Jesus?

Scripture Reading: Matthew 2:1-23 and Luke 2:8-20

I am going to say something controversial: I think the movie, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, is Will Farrell’s funniest movie. Ya, Elf is a modern classic at Christmas. Ya, Anchor Man is probably the most quotable. However, Talladega Nights has a moment in the movie that gives one of the most pointed comments on popular cultural Christianity.

Ricky Bobby is a champion Nascar Driver, and there is a scene at the dinner table where he is instructed by his wife to say grace in order for God to continue to bless them with more Nascar victories.

Rick Bobby prays, “Dear Lord Baby Jesus,” and as he proceeds to thank the baby Jesus for all the good things he has, his wife stops him and says, “Sweetie, you know Jesus grew up, right? It’s kinda weird to pray to a baby.” Rick Bobby responds indignant: “I like the Christmas baby Jesus the best. If you say grace, you can pray to whatever Jesus you want: teenage Jesus, bearded Jesus, whatever.”

After which, his friend chimes in and says, “I like to picture Jesus in a tuxedo T-shirt…because it says, like, I wanna be formal…Right. But I’m here to party, too. Because I like to party, so I like my Jesus to party.”

His son pipes up and says, “I like to picture Jesus as a ninja fighting off evil samurai.”

This goes on for a little bit; Ricky Bobby continues to pray: “Dear 8-pound, 6-ounce, newborn infant Jesus… don’t even know a word yet…just a little infant and so cuddly, but still omnipotent… we just thank you for all the races I’ve won and the 21.2 million dollars…Love that money! Amen.”

Now, I hope no one is offended by my quoting this in church, but while this scene is ridiculous and theologically wrong, it also speaks of a kind of culture that has mixed consumerism with popular Christian religion, the cult of prosperity and achievement, health and wealth, with biblical illiteracy: Jesus is who I like him to be.

According to a 2015 survey by the Barna Group (and admittedly, these are American statistics), people believe the following things on average about Jesus: The vast majority of people believe Jesus was a real person. “More than nine out of 10 adults say Jesus Christ was a real person who actually lived.” However, “Younger generations are increasingly less likely to believe Jesus was God…Most adults—not quite six in 10—believe Jesus was God, while about one-quarter say he was only a religious or spiritual leader like Mohammed or the Buddha. The remaining one in six say they aren’t sure….” There is similar confusion about Jesus’ life: “About half agree, either strongly or somewhat, that while he lived on earth, Jesus Christ was human and committed sins like other people.”

That is perhaps somewhat typical given what we assume about living in a post-Christian culture, but one of the surprising statistics found was that the overwhelming majority of Americans say they have made a commitment to Jesus at some point in their lives.

What does this mean? David Kinnaman, President of Barna Group, commented at the end of the study: “This impressive number begs the question of how well this commitment [to Jesus] is expressed…dedication to Jesus is, in most cases, a mile wide and an inch deep.” As I said, these are American statistics, and you can imagine smaller numbers but similar factors going in for us.

It appears that there are lots of people familiar with Jesus in our culture, but not a whole lot that actually want to follow him. Lots of folks agree that Jesus claimed to be God, but that ultimately means they can carry on with their lives no different than those who don’t.

Pastor Chris and I got together for lunch one day, and out of that conversation came the idea of a series going through moments in Jesus’ life, taken from the four Gospels: His incarnation, core teachings, death, and resurrection, unpacking what these mean. So, that is what we are going to be up to leading up to Good Friday and Easter.

We have made Jesus Safe, Sweet, and Sanitized

Again, while Ricky Bobby is a buffoon in a comedy movie, what he says is brilliant satire. Notice how he prefers the Christmas Jesus, which, for him, means that Jesus is warm and cuddly in a golden diaper. I suspect many of us have a depiction of Christmas, as well as the portrayal of Jesus and his teachings, in our heads that is similarly safe, sweet, and sanitized.

Some of our Christmas Carols don’t help. Take “Away in a Manger”: “The cattle are lowing, the poor baby wakes / But little Lord Jesus, no crying He makes.” Why would someone assume that Jesus, as an infant, did not cry, whether hungry for his mother or because he had a dirty diaper? Isn’t Jesus human in all the ways we are human?

Take “Silent Night”: “Son of God, love’s pure light / Radiant beams from Thy holy face.” I love the song “Silent Night,” but I clench my teeth a bit when it depicts Jesus with beams glowing from him.

“All is calm, all is bright…” Why do we assume everything was calm? According to Luke’s Gospel, Mary, and Joseph got into Bethlehem, and it was so crowded and chaotic that she had to give birth in what is probably most accurately the equivalent of an alleyway, where the household animals were kept and were probably dangerous, loud, and dirty. Jesus is laid to rest not on golden, soft hay but in an animal’s feeding trough (some of you folk know full well what that might look like—it probably had bits of slop in it). Jesus was wrapped not in beautiful, bleached linens, but the word in Greek describes the ragged bands of cloth one used during traveling, wind-torn and caked with sand.

Those are details of Luke’s Gospel, and when we come to the events of Epiphany and the visit of the wise men in chapter 2 of Matthew, we have to admit this story has been packaged and sanitized as well.

By the way, I called it Epiphany—did you know that it is called Epiphany? I didn’t know this until literally four years ago when I preached at another church over the Christmas break, and I spoke on an unrelated scripture and was scolded for not upholding the church calendar, which apparently has 12 days of Christmas like the song says (that always puzzled me growing up—why are there 12 days?—also why does a person’s true love give them a bunch of birds?) I get the golden rings but If my true love gave me “eight geese a-laying,” can’t say I would feel very Christmasy about it. I apologize if I have yet again ruined another Christmas song for you.

Well, Epiphany is the last day of Christmas, twelve days after Christmas day that usually celebrates the next event in the Gospels: the dedication of Jesus in Luke, the coming of the wise men in Matthew, and the baptism in Mark and John, who do not have a birth narrative in them. Again, don’t feel bad if you did not know that. My family still puts the Christmas tree away after New Year’s.

However, as further evidence that we have the idea of Christmas so often packaged to us, in a lot of Christmas scenes, you have the shepherds at the manger scene from Luke’s Gospel with the wise men from Matthew’s. But notice what Matthew says: Jesus was a child when the wise men found Mary and Joseph living in a house in Bethlehem. This is a different timeline from Luke’s version.

Matthew tells the story differently and emphasizes certain things he wants his readers to see about Jesus. The churches of Matthew’s day were facing persecution and expulsion from the Jewish Synagogue: Jewish Christians, who seemed to be Matthew’s audience, were being seen as heretics and apostates for following Jesus. This compounded an already tense state of affairs where the people lived under Roman occupation, under the boot of a tyrannical empire, where violence and oppression were already a daily reality.

Again, we so often present the Christmas scene with clean and calm figures, but that is simply not the case for Matthew’s Gospel, which sets the scene for Christmas with a backdrop of tyrants, intrigue, and a bloodshed. That probably would not go as well on someone’s front lawn with lights and bows. Your front lawn would like that guy by Aldershot School that goes way too far in his Halloween decorations. You know who I am talking about, right?

If any of these elements of the story is a surprise to you as it was to me when I learned about them many years into my adult walk with Christ, I think we all have inherited our own pleasant, packaged, safe, and sanitized version of Jesus.

One reason why we like a safe and sanitized version of the Jesus story is that we don’t have to actually contend with what the Gospel demands.

When I was pastoring First Baptist Church of Sudbury, I had a congregant complain after I preached a sermon mentioning the Charleston shooting. This was in 2015. A deranged white nationalist walked into a church in a black community and killed nine people at prayer, hoping to start a race war. I had someone complain that I was mixing politics and religion in the sermon. I was confused by that criticism because that sermon never mentioned politicians, political parties, voting, or anything of the sort.

I soon found this man, a man raised in the church his whole life and even served as an elder in another church, openly espoused that he did not think Jesus ever spoke about racism or justice and even said to me that he did not think racism was sinful. I soon realized that despite his objection, he very much did mix religion and politics. It was just the worst version of both.

His was an extreme case, but we all so often give into a picture of Jesus, sweet, safe, and sanitized, that absolves us from having to do something about it.

1. A Different Jesus: True Moses, True Israel

But Matthew is different. Matthew presents a different Christmas story and a different Jesus. He is barely done mentioning the birth of Jesus when he starts mentioning the politics of Jesus’ day. It says the people were ruled by King Herod. Herod was a tyrant. Herod was not ethnically a Jew, but he claimed to be a faithful Jew for political purposes, nor did he have a royal lineage. His mother was from Arabia, and his father was an Edomite who found favor with Rome because Rome wanted a puppet king over these lands. Herod remained in power because he was very good at squeezing the people for more tax money to fund the imperial war machine, and he was absolutely ruthless at dealing with any threat to his power. In fact, he killed several close relatives who he thought might challenge his power.

Yet, a group of wise men from the east show up at his door wondering where the new king of the Jews is because a certain star sign has risen. Herod’s title was king of the Jews. You can imagine today’s ambassadors showing up to the White House asking the President, “Hey, we are here to honor your country’s new and true President. Where is he?” Yes, the messiah is political, just not in the way earthly politics want him to be.

Herod tries to trick and scheme, then intimidate and murder his way to stay in power, but God whispers in the dreams of the wise men and of Joseph, and both get out of Bethlehem before it is too late.

Matthew says that the holy family fled the massacre to go to Egypt and that they returned home years later when Herod was dead, coming to reside in Nazareth.

By doing this, Matthew’s story makes two subtle references here that tell us who Jesus is.

Who do we know in the Old Testament that had to escape the slaughter of infants? Moses the man who gave the Jewish people the law. In Matthew’s time, Christians are being attacked because their radical way is seen as a betrayal of the Jewish law, yet here, Matthew wants to say that Jesus is not only like Moses, Jesus is the true Moses. Jesus is showing us the true way to be faithful to God. And so, Jesus says in Matthew, “I have not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it.”

Second, who in the Old Testament came out of Egypt? Israel did. God’s people did. Matthew says that these things were done to fulfill what the prophet said, “Out of Egypt I called my son.” That is a scripture from the prophet Hosea, and if you look at it, Hosea is talking about the people of Israel as God’s child, and Matthew sees this as pointing to Jesus. Again, as Jewish Christians in Matthew’s time were persecuted and excommunicated from their families and friends for worshiping Jesus, Matthew says that Jesus is the true Israel. What God was longing to do with his people, a people set to be a redeeming presence to bless the rest of the world, God is fulfilling this first and foremost through Jesus and Jesus’ way. This is what God’s people are meant to be like.

Now, Christians throughout history have looked at passages like this in Matthew and concluded two problematic things: one is that God is done with the Jewish people or, worse, the Jewish people are evil for rejecting Jesus. This has led to some terrible stuff in church history. Others today do the opposite and look at what the modern state of Israel is doing in Palestine and automatically assume that Christians should support this country because this is biblical Israel. Matthew suggests something different.

If Jesus is the True Moses and the True Israel, God has not forsaken the Jewish people. Paul says the promises of God are irrevocable. Jesus is the very sign that God had refused to give up on his people. However, this also comes with the challenge that God’s people are called to follow God’s ways not the ways of this world, and God’s ways are most clearly shown in Jesus.

2. A Different Way: Jesus’ versus Herod’s

Between God and the world, we all have that choice presented to us.

Jesus’ way is different, and it is in brutal contrast to Herod’s.

Herod’s way of ruling involves lying and scheming, deceiving the wise men.

Herod’s way looks to religion to manipulate and maintain his power.

Herod’s way, worst of all, believes that peace and order are maintained by violence, even killing the innocent.

Herod is an especially cruel tyrant—he was a paranoid psychopath—but Herod’s way of ruling is known all too well:

It is the way that sees truth purely as what one wants it to be.

It is the way that puts one’s comforts always ahead of another’s needs.

It is the way that treats others as objects, valuable only if useful and worthless if not.

It is the way that looks at one’s enemies and sees something only to humiliate or annihilate.

It is the way that looks to God and sees religion as a source of power and God as nothing but the idolatrous echo of one’s ego.

Yet, just one chapter later, we see the contrast to Herod’s way as Jesus begins to announce the kingdom of heaven:

A kingdom not for the people who think they are spiritually rich but for the poor in spirit.

A kingdom not for the prideful and powerful but for the humble and humiliated.

A kingdom not for the compromised and the complicit but the pure and the peacemakers.

A kingdom for those willing to sacrifice for the sake of what is true and right, just as the prophets did.

That is Jesus’ way, and it cannot be reconciled with the way of Herod. Jesus is the narrow path that leads to life, whereas Herod’s way is the wide highway that leads to destruction.

3. Different Seekers

Which way are you on? Will you seek Jesus? In Matthew and Luke, it is surprising who does. Jesus has seekers who are different from what we expect.

The wise men seek Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel. Who are these wise men? Tradition gives them names and says there were three of them, one for each gift, but Matthew offers no specifics. Who are wise men? The word in Greek is “magos,” and it is used in the Old Testament for Pharoah’s magicians that oppose Moses in the Book of Exodus and the officiants of the king in the Book of Daniel. These are not particularly positive references: these men are a king’s astrologers and fortune tellers, and often, a king would send officials like them to honor an allied king. In the year 66 AD, magi from an eastern nation beyond the Roman Empire visited the emperor Nero to honor him.

Whoever Matthew’s magi were, they came to recognize Israel’s true king, even though they had no relationship to God’s covenant with Israel, and they are the ones who found Jesus while Herod and the rest of the people in Jerusalem were clueless. Let’s just appreciate this little irony of the story: When God’s people completely miss their messiah being born on their doorstep, a group of pagan fortune tellers travel across the known world led by an ancient horoscope in the sky, a notion Jews would have regarded as false—everything their religion stood against—but the magi did so to find and honor Jesus.

That might lead us to be a bit more humble in how we speak about people of different beliefs than us. For all we know, they may actually be pursuing Jesus—or Jesus is pursuing them—in ways we have fundamentally missed in our own lives.

In Luke’s Gospel, it is the shepherds who seek Jesus. Shepherding was one of the poorest jobs one could have in that society (and not to mention dangerous, out in the wilderness with the elements, wild animals, and bandits). It was a job for outcasts. The shepherds come and find Jesus, and the angels say that you will find your messiah wrapped in ragged cloth and lying in an animal feeding trough, a manger, and these things will be a sign to you of God’s good news for everyone.

If this event were to happen here, today in Kentville, you can imagine Jesus being born by the dumpers in a parking lot at center square, wrapped in someone’s second-hand coat, and the poor, the drug addicts, the folks that work night shift at the gas station or in the warehouse at Walmart realize if this baby is going to be our leader, things are going to get better, but he’s one of us.

A messiah born into poverty rather than power and privilege: This messiah is good news. He gets us. He is on our side because if God is on the side of the least of us, God is for everyone. And so the shepherds search out Jesus. Will we?

This chapter ends with the full display of what Herod is capable of: a massacre of the children in Bethlehem to try to find and eliminate Jesus. Matthew says this speaks of another prophecy from the book of Jeremiah chapter 31, “Rachel weeping for her children / She refused to be consoled because they are no more.”

Scholars have been puzzled about how this passage is actually a prophecy. It does not actually predict anything specific. It just speaks poetically of Rachel, one of the matriarchs of Israel, weeping over the casualties of the fall of Jerusalem several hundred years before Jesus. These were people slaughtered by the invading Babylonian army, who then carried off the survivors into exile. It speaks of the despair the survivors expressed as they mourned their deceased, walking off into slavery with nothing but ash and rumble behind them. Matthew cites it and by doing so connects their pain with the pain of the victims of tyranny in his day. And by doing so, anyone who read this and knew that scripture would also know what that passage promises to those who have suffered tragedy. The verses before and after proclaim hope. They say,

The Lord will ransom you…

I will turn your mourning into joy;

I will comfort you and give you gladness for sorrow…

There is hope for your future, says the Lord…

I will surely have mercy…

I will satisfy the weary,

And all who are faint I will replenish.

To the victims of tyranny and tragedy, Matthew is saying there is hope. Through Mary and Joseph, through wise men and shepherds, Luke and Matthew have been giving us unlikely examples as signs that if God is with these kinds of people, God is with us all.

To the victims of the violence in the Middle East, to those who have lost so much to the war in Ukraine, to those in Japan sifting through the remnants hit by the earthquake, to the broken and the hurting, the starving and the scared, God is with you. God is for you. God will ransom you. God will restore you. God will have mercy. There is hope.

God’s kingdom is here, and this is good news.

Jesus’ way is different because Jesus isn’t like how the world operates. He does not conform to our assumptions and expectations.

God cannot be bought, boxed in, owned, or sold off. God has come as the gift of grace, unlimited as it is undeserved.

Trust it. Let it sustain you in tough times. Let it transform you. Let it flow through you to transform others.

Let’s pray.

Loving and gracious God revealed in Jesus Christ.

You are God, Immanuel. God with us, God for us.

You lead as the true Moses; you teach us what it means to be Israel.

God, we repent for all the ways we honor you with our lips, but our hearts and our actions are far from you and your ways.

Forgive us and guide us by the leading of your Spirit on the way of Jesus.

We pray for these things in your name, amen.

The More Lost, The More Loved

Are you the kind of person who loses their car keys all the time? Full confession: I am. My wife is giving me that look like, “Oh yes, he is, and it drives me nuts.”

“Honey, where are the car keys?” She has asked.

To which I respond, “Well, they are either on the key hook, or on my dresser, or on my desk, or in my coat pocket, or in my pants pocket from the previous day. It’s a simple list of options, Meagan.” To which she looks at me like that.

It is amazing how important a set of keys can be at the right moment. The other day, I was doing work on our vehicle, and I went into the house. I was in there for a bit, and I realized I had to go somewhere. Where are my keys? Where did I leave them? When I came back out, thinking I might have left them in the vehicle, there they were. I could see them through the glass, but—and you know where I am going with this—the door—I realized out of habit, I locked the door and closed it.

This was a holiday, and so I figured CAA would either not be around or charge an arm and a leg to come or take forever to come. So, I tried to get in the car with a coat hanger and something I was using to wedge the door forward a bit. I came so close to getting the hook on the door handle to open it. So close. I have never wanted to get those keys so bad in my life.

In the end we called CAA. They came pretty quickly. They had a special tool that got the door open in about three seconds.

Anyways, you don’t realize just how important something is until it is lost.

So, as I said last week, Pastor Chris slotted me in for two weeks during his vacation way back when. It was when he was going through his series on the parable of the Prodigal Son, and my thought was to go into some of the parables, particularly the two that occur before the Prodigal Son in Luke chapter 15: the Parables of the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin. These are two parables that I keep coming back to, reflecting on. They go like this:

15 Now all the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. 2 And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” 3 So he told them this parable: 4 “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? 5 And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices. 6 And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and neighbours, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my lost sheep.’ 7 Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance. 8 “Or what woman having ten silver coins, if she loses one of them, does not light a lamp, sweep the house, and search carefully until she finds it? 9 And when she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin that I had lost.’ 10 Just so I tell you, there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents.”

Gospel of Luke 15:1-10, NRSV

I have been enjoying reading a collection of sermons on the parables as I reflect on these passages. It is a book by Howard Thurman. Thurman was a mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr., and his books have been as beautiful as they are challenging for my faith. In his sermon on these parables, he suggests something profound: Sometimes, we take the parables as stories merely about how to get saved, which is an important topic, of course. But let me suggest to you that if you read these parables asking, “What do I do?” You have fundamentally misunderstood it. Thurman pointed out to me that these parables are whole accounts of God’s character in miniature. They are here to tell us what God is like and what God does.

So, the parable asks this question: What is God like? In these parables, Jesus gives us two surprising metaphors that answer this question.

What is God like? God is like a Shepherd

The first might seem obvious or old hat to some of us who have been around the church for a while, but it is surprising because it is loaded with implications. If you look at certain passages in the Old Testament, God is the shepherd of Israel.

But notice something: Jesus is scolded by religious teachers because he is the one eating with the riff-raff of the town. Sinners and tax collectors are coming to him, finding the grace they have never experienced, and religious folk are indignant. To this, Jesus says that God is like a shepherd who goes out and rescues a lost sheep and that heaven rejoices each time one lost sheep is brought home. Who is this heavenly shepherd in this parable, then? Its Jesus. Jesus just gave us a clue about who he is here. Jesus is God Immanuel, God with us.

But notice something further: What is God like if God is like Jesus? Is God the kind of God that loves only his flock? Does God only love the ones that stay in the flock, who are smart enough and competent enough and loyal enough to keep themselves out of trouble? Is that what God is like? Is that what Jesus is like? Hold that thought for a moment.

What is God like? God is like a Poor Woman

The second metaphor is even more surprising. God is a woman who has lost a coin.

I know what you must be thinking: “You mean God isn’t an old white guy with a long white beard up in heaven?” Believe it or not, while Jesus certainly uses the analogy that God is like a Father for very important reasons, there are other passages that say God is like a mother who comforts her children, or God is Lady Wisdom who guides Israel, or God is a mother bird protecting her young. Look them up. They are worth a Google. The Bible speaks about God in a number of ways to communicate God’s love, and here, Jesus uses the analogy that God is like a woman searching for a coin.

Now, who is this woman? We are given some clues: She has ten coins. A silver coin was a day’s wage. Angela suggested last week that ten silver coins could have been her dowry (the money her father set aside to pay for a wedding); sometimes, the ten coins were laced together onto a headdress for unmarried women to wear. Either that or it could be her life savings. Whatever the case, it suggests she is very poor. If it is her dowry, in a culture where women had very little, marriage was the means of provision and stability. This coin was her future. Or, if it was her life savings, as you can imagine, having only ten days’ worth of savings is not much, and losing even a little would cause panic and desperation. This could be money for her next meal.

It also says she lives in a home that apparently does not have windows (she needs to light a lamp in order to see). In other words, her home is not large and not that nice. This is a person that lives on the brink of destitution.

Desperate and destitute—let’s just let this sink in for a second: God is like a poor, desperate peasant woman looking for the money that she desperately needs to sustain her well-being. If you did not know it was Jesus telling this parable, you might feel like this is an irreverent idea. God is like a woman? God is like a poor woman? God needs the lost desperately?

It begs the question: Do we matter to God? Do the lost matter to God? If so, how much? Is God the kind of God that is unaffected by whether we are saved or not? Or is God like a poor woman desperately trying to find her lost coin?

I was raised with a certain belief about God that said God is the kind of God that chooses some to be saved, some to be God’s elect, and the others, God in his sovereignty, chooses to leave them in the judgment of their sin that they rightly deserve. Perhaps you were raised with that belief, or perhaps you are looking at me thinking, “What! There are Christians that believe that?” Yes, a lot of them, actually (particularly in the United States for some reason), and they find lots of interesting verses in the Bible to support this idea. But then again, you can cobble together a verse here or there in the Bible to justify almost anything.

Now, if you were raised with an idea like that, you probably were also taught that this was a very good and biblical idea because no one deserves to be saved (which is true), but God, in his grace, has chosen certain ones to be saved, and thank goodness, you are one of them.

Many Christians get by immensely comforted by this notion, but to me, as a young man, it caused profound distress. How could God love some with a saving love and not others? How could God love anything with a less-than-perfect and powerful love?

This became particularly disturbing when a person started coming to the church I attended with my family. He came to faith from a completely non-religious background. I remember him being so passionate about God, and, of course, the church rejoiced. He was the evidence that we were reaching the lost. In fact, I remember, right around that time, a sermon on this very parable, praising how this church was seeing the lost sheep come home.

However, as I learned, this young man had a lot of difficult stuff in his life, and one Sunday, I noticed he just stopped coming to church. When contacted, the guy just said he wasn’t interested in all this religious stuff anymore. It wasn’t helping him with whatever he was going through (which, to this day, I don’t know what that was).

This created a dilemma for me because I was raised with the notion that God chooses some for salvation, and for those he does choose, we would say the phrase, “once saved, always saved.” And so, I had to ask my pastor: Is this person still saved? And if so, how could he just walk away from his faith like that? My pastor thought about this and said, with a bit of ire in his voice, “Obviously, he just wasn’t saved to begin with then.” He thought this was a satisfactory answer to my question.

I did not think so. You see, if a person that at one point confesses Jesus is passionate for him as this person clearly was, but then gives up their faith—if this person was never saved, to begin with, how can anyone really know whether they are saved? If eternal security works like that, how can anyone feel, well, secure? I didn’t.

I can tell you that many times in my younger years, I worried whether or not I was saved. Because if God is the kind of God that has only chosen some people to be saved and others not, and there is a whole bunch that think they are saved but actually aren’t, I needed to know for certain that I am one of those chosen, and the only way I could know, I reasoned, is that I believe the right things, I do the right things, or I feel close to God, all of which confirm in some way that God chose me.