Tagged: Jesus CHrist

The Why is Love: Advent and Incarnation

“All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: ‘The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel” (which means “God with us”).’” (Matt. 1: 22-23)

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth.” (John 1:14)

“For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things…” (Col. 1:19-20a)

There is a movie by the Coen brothers called Hail, Caesar. The movie is, well, about a movie. A movie studio is filming a movie about the life of Christ through the eyes of a Roman soldier, played by George Clooney, who we find out gets kidnapped. I won’t ruin any more of the plot. If you have ever watched a Coen Brothers movie, you will know that it has witty, dark, dry humour.

And, in my humble opinion, one of the best scenes of the film is also, believe it or not, deeply theological. I think all the best scenes of every film are theological, but whatever.

In this film about a film, Josh Brolin plays the manager of the movie studio, who is shooting this film on the Christ. Brolin, whose character is named Eddie Mannix, knowing this film is going to be the biggest film of the year (think something like the old Ten Commandments or Ben Hur kind of movie), gives a copy of the script to a panel of religious experts: an Eastern Orthodox patriarch, a roman catholic priest, a protestant minister, and a rabbi.

And I know what you are thinking, what next, they all walk into a bar? Not quite.

Brolin’s character explains that this prestige picture is aiming to tell the story of the Christ powerfully and tastefully, so he wants to see if the story is up to snuff.

The Rabbi pipes up: “You do realize that for we Jews any depiction of the Godhead is strictly prohibited.”

Eddie looks at him, disappointed. He had not considered this.

But the Rabbi continues: “Of course, for we Jews, Jesus of Nazareth was not God.”

Eddie looks again, confused but also pleased. He reiterates again that he wants to make sure that the script is realistic and accurate and would not offend any American person’s religion.

The Patriarch blurts out, “I did not like the chariot race scene. I did not think it was realistic.”

Eddie again is confused.

The Priest jumps in: “It isn’t so simple to say that God is Christ or Christ God.”

The Rabbi agrees: “You can say that again, the Nazarene was not God.”

The Patriarch, waxing mystical for a moment, replies: “He is not not God.”

The Rabbi exclaims: “He was a man!”

“Part God also,” says the Protestant Minister.

“No, sir,” says the Rabbi.

To which Eddie turns, trying to smooth things over, but also clearly out of his element: “But Rabbi, don’t we all have a little God in all of us?”

The Priest jumps in again and finishes his thought: “It is not merely that Jesus is God, but he is the Son of God….”

Eddie is now confused: “So are you saying God is all split up?”

“Yes,” says the Priest, “and no,” suggesting it is a paradox.

Eddie is now deeply confused. “I don’t follow…”

The Rabbi interjects: “Young man, you don’t follow for a very simple reason: these men are screwballs! God has children? What, next a dog? A collie, maybe? God doesn’t have children. He’s a bachelor. And very angry!”

The Priest is upset: “He only used to be angry!”

Rabbi: “What, he got over it?”

The minister accuses the Rabbi: “You worship the god of another age!”

The Priest agrees: “Who has no love!”

“Not true!” says the Rabbi, “He likes Jews!”

The minister continues: “No, God loves everyone!”

“God is love,” insists the Priest.

The Patriarch jumps in: “God is who he is.”

Rabbi replies, upset: “This is special? Who isn’t who is?”

Everyone is getting frustrated with each other.

The Priest tries to bring the conversation back around: “But how should God be rendered in a motion picture?”

Rabbi exclaims, exasperated: “This is my whole point: God is not even in the motion picture!”

Eddie turns, sinking into his chair: “Gentlemen, maybe we’re biting off more than we can chew.”

Now, I probably did not do this scene justice. You will have to watch it yourselves. I showed it to my wife, who, for some reason, did not laugh as hard at it as I did.

Today, we light the love candle. It is the candle we light on the way to Christmas, where we celebrate the deepest mystery of our faith: the incarnation of Jesus. This Advent season, I have been reading a wonderful little Advent devotional compiled from the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, called God in the Manger (I deeply recommend this to you for next year’s reading). Bonhoeffer was the German pastor who opposed Hitler, sought to organize the church against the power of the Nazis, and was executed, falsely accused of being a part of an assassination plot.

For this week of Advent, the candle of love, the devotional turns to the question of incarnation, why and how is God with us in an infant, born in a stable? Why and how did God become flesh? Why and how was the fullness of deity pleased to dwell here, bodily? How is that possible?

The questions might evoke the same response as Eddie in Hail Caesar: “People, I think we have bitten off more than we can chew!”

Such ideas feel at best unanswerable: above our pay grade as humans. Or at worst illogical, prone to the endless arguing that the Rabbi, Priest, Minister, and Patriarch fell to.

How the Incarnation?

Yet, this question—how and why did God become human?—is the question that all of Christian faith rests on.

How and why did God become human? This week, we light the love candle, and I am going to suggest that incarnation and love—the two are inseparable.

Now, you might insist, that does not really answer the “how” question exactly.

Indeed, let me put the question this way: God is infinite, all-powerful, present to all things, everywhere, all knowing, transcendent, above and beyond all things—how can God be found in human form, let alone the form of a baby?

Put that way, it sounds like trying to fit the ocean into a shot glass. It does not seem like it can work.

Frederick Buechner once said: It feels like a vast joke that the creator of the universe could be found in diapers! He goes on to say, however, that for those of us raised in the church who have grown up with this idea, until we are scandalized by it, we can never take it seriously.

How can God come in human flesh?

As you can imagine, Christian thinkers have found this a bit difficult to answer. Some have said, well, maybe Jesus wasn’t fully human, he only appeared to be human—sort of like how Clark Kent is Superman and only appears to be a mild-mannered reporter. He appears human, but he is actually Kryptonian.

Others came around and suggested that maybe Jesus is not fully God. Perhaps he is like God or has a part of God’s presence in him, but God, the real God, is up in heaven, untarnished by the world, away and transcendent.

Others came around and said, maybe Jesus has the mind of God and the body of a man, or maybe Jesus had something more like a split personality: a divine person in him and a human person in him.

Again, you might be getting the feeling that we have bitten off more than we can chew.

Each of those answers, Christian tradition has found to have its problems. And the ongoing commitment Christians keep coming back to is that in all the ways God is God, Jesus is God. In all the ways humans are humans, Jesus is human, except without sin. Jesus has “two natures.” Well, that still does not answer the question. that still feels like the ocean in the shot glass problem.

Does that mean baby Jesus was omnipotent? Was a little infant, who cannot speak was also all-knowing, knowing about the paths of comets on the other side of the universe? That still sounds like one nature is swallowing up the other.

Bonhoeffer reflects on this problem, and he answers it this way: “Who is this God? This God became human as we became human. He is completely human. Therefore, nothing human is foreign to him. This human being that I am, Jesus was also. About this human being, Jesus Christ, we also say: this one is God. [But] this does not mean that we already know beforehand who God is.”

In other words, Bonhoeffer is trying to tell us that when we look at Jesus, he does not merely fulfill what we expect God to be like in the human Jesus, but he fundamentally redefines God, upsetting our assumption about what God must be like.

He writes, “Mighty God is the name of this Child [based on Isaiah 9:6]. The child in the manger is none other than God himself. Nothing greater can be said: God became a child. In the child of Mary lives the almighty God. [But] Wait a minute!… Here he is, poor like us, miserable and helpless like us, a person of flesh and blood like us, our brother. And yet, he is God…Where is the divinity, where is the might of this child?” Bonhoeffer answers, “In the divine love in which he became like us. His poverty in the manger is his might. In the might of love, he overcomes the chasm between God and humankind…”

How does God, the infinite, transcendent, all-powerful God, become a finite, vulnerable, human baby? The only answer we have is that God is love. Because God is love, God can be all that God needs and wants to be for us. God desires to be with us. So God can.

One church father, Gregory of Nyssa, put it this way: God’s true power is to be even things that God is not. For God to become a lowly and vulnerable human, this is not something that contradicts his power, but rather it is proof of his true power, the power of God’s love.

If we start thinking, you know what makes God a God? Power! If what we worship as God is something we understand as power first and foremost, we will forever see the life of Christ as a scandal. Worst still, we will also probably come dangerously close to worshiping human power as something “god-like” as well.

But if God is essentially love, perfect love is capable of drawing close to us in weakness and vulnerability, and that, ironically, is true power.

That still leave my answer somewhat inadequate. I don’t understand all the mysteries of God. But love is the best clue we have.

Thankfully we don’t need to solve theological mysteries in order to trust them and to be saved by them.

Why the incarnation?

Now, if God was able to become human because of love, maybe we need to back the truck up for a second and ask, why? Why did God need to do this?

Afterall, God is portrayed as loving and gracious in the Old Testament. What does Jesus add to it, if we can call it that? Could God just keep telling us that he is love and that God loves us?

Let’s ask it this way: Why does love need a body?

Modern times cast humans as brains on sticks—the fact that many of us live and work barely moving our bodies as we type on computers can lead us to believe this.

We are told messages that we can surpass the limits of our bodies by sheer willpower; some of us, when we were younger, actually believed that. Then you get a sports injury, and next thing you know, your body aches for no reason, and you catch yourself groaning every time you bend over to tie your shoes. Our bodily’s limits catch up with us.

Some of us don’t particularly like our bodies. Our bodies represent our weaknesses, our vulnerabilities, our imperfections. Companies love preying upon our bodily insecurities to sell us more products. Buy this to fix your hair. Buy this to help lose weight. And so on.

Stanley Hauerwas, Professor at Duke University, wrote one of the great books on Christian medical ethics, called Suffering Presence. In it, he reflects on how medical ethics made him profoundly aware of the significance of our bodies.

He tells this one story of a nurse he interviewed. The nurse worked in a branch of the hospital that dealt with severe infections. Severe inflections have a way of making people hate their bodies. I remember one time in high school, I had a severe tissue infection in my forehead, and I woke up looking like a character from The Goonies. Let’s just say it took a few years for my self-esteem to recover.

Well, for some of these folks with severe infections—gangrenous, swollen infections—the nurse reported that often the people would just want their limbs amputated. Faced with the threat of severe infection, some patients quickly concluded their limbs, their bodies, are irredeemable.

What did she do to prevent that mentality? The nurse spoke about how, when she did her rounds, she would make a point of touching the person’s limbs, even if that strictly was not necessary. You can tell a person their limb is okay, but having a person touch their bodies, the nurses said, reminded them that they were worth saving.

Why did God take on human flesh? Why was the fullness of deity pleased to dwell bodily?

To remind us that our bodies are worth saving.

We can start to see why then that the church fought so much about all this theology about Jesus being fully God and fully human: if there was an element of our humanity that God was not apart of fully, not at one with fully, not able to be found there fully, then that part remained unredeemed. If Jesus is not anything less than fully God and fully human, God is not with us.

Because the Incarnation…

There is a hymn that goes like this:

Good is the flesh that the Word has become,

Good is the birthing, the milk in the breast,

Good is the feeding, caressing, and rest,

Good is the body for knowing the world,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the body, from cradle to grave,

Growing and ageing, arousing, impaired,

Happy in clothing, or lovingly bared,

Good is the pleasure of God in our flesh.

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the pleasure of God in our flesh,

Longing in all, as in Jesus, to dwell,

Glad of embracing, and tasting, and smell,

Good is the body, for good and for God,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.

If you look at so many of the religions around the time of the church, you will see a startling fact: nearly all of them did not care about bodies.

Romans and Greeks often had a deeply tragic outlook on life.

Egyptians were obsessed with escaping this life into an afterlife.

Gnostics believed that if you were spiritual, it did not matter what you did with your body. In fact, salvation was found in escaping from your body. The body was evil.

Eating and bathing, sex and sleep, for many, these were fallen and evil things. Sadly, there are a lot of Christians who still have that mentality today: to be spiritual is in some way to disregard your body, get away from it. The body, for some, is at best an obstacle to be conquered and, worse, a thing to be ashamed of.

However, one reason why Christianity grew in the ancient world is that it rested on a revolutionary truth for people: If God became human, you matter. The incarnation says that God made the world very good. The goodness of creation is a part of what it means to have a body, the body God gives us, the body God is pleased to dwell in. Your life matters.

Because God took on flesh, because God was found in a body, there is nothing we experience that is meaningless to God.

Our hunger and needs, our frustrations and pleasures, our vulnerabilities and our strengths, our desires and dreams, our thoughts and emotions, every event, right down to every mundane moment, these all matter to God. God is found there.

What writer says the message of the incarnation means that “there is nothing so secular that it cannot be sacred” (Madeleine L’Engle).

Whether it is singing in church, answering emails at work, eating a bowl of cereal in the morning, or lying still at night: every moment can be the site where God meets with us. Every moment can be a place where we know God’s love finds us. Why? God came in Jesus, God Immanuel: God with us.

And because God took on flesh, we also know God will never let us go. No matter who we are or what we have done. God is on our side. Paul puts it this way:

“For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38-39)

How did God become human? Why did God become flesh? How do we know we have forgiveness and hope? This morning, we lit the love candle. In it, we have the foundation of our faith: Because God loves us so much, because God is love, God became one of us.

Let’s pray:

Defending Jesus: The Olympic Games, Depicting the Last Supper, and Learning How to React in a Post-Christendom Culture

The Olympic Games opening ceremony featured what seemed to have been a parody of the painting from Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper; only the members of the supper were represented by drag performers. And, in case you live under a rock or are one of those blissful souls who are not on any social media, the reaction to this has not been positive. The organizers gave a somewhat half-hearted apology, but again the reaction to that has also not been positive.

There is something about all this that feels like the internet just being the internet. Did you know that the Christmas Starbucks Cup is now only green and red? Did you know there is an ice cream store called “Sweet Jesus”? Did you know someone somewhere changed the words to a Christmas song? Excuse me while I yawn and keep scrolling. However, there is something about reacting this way to things in the name of faith that is a whole lot more disconcerting to me.

To put it one way, I think the offense at the offense is worse than the original offense. I remember seeing the display of the Last Supper and thinking, “That’s odd and a bit in poor taste, but if they want to do that, oh well,” and then I pulled up that day’s Wordle to crack (I admit, yes, I still play Wordle). Then I watched post after post of people losing their minds over this, shaming everything from the entire Olympics to the whole country of France to pronouncing God’s judgment over every non-Christian everywhere that wasn’t offended at this. To that, I don’t know what to say to that. In internet-speak: Insert meme where Jean Luc-Picard face palms here.

Perhaps in the grand scheme of things, I just believe there are so many more important things to be upset about. Perhaps, in my old age, I have grown desensitized to internet hoopla. Perhaps, I am the one that isn’t normal. Perhaps, I am okay with that. But if you are reading this thinking, “Yes, Spencer, there is something wrong with you; you as a Christian need to be upset about this,” let me suggest that, perhaps, getting upset makes its own unintended offenses.

Speaking of being upset, I want to take this time to point out an irony that I so often see. I watch right-wing folk complain about how “woke” the left is, how it is always offended at things, and how this portrays a lack of emotional stability or something like that. Well, sometimes, the thing we hate in another is what we embody ourselves, and we just can’t see it. Pause and reflect on that one.

Now, indulge me for a second if you are a Christian. We live in a secular culture. We live in a culture where Christianity has taken on layers of negative connotations based on its past, a past typified by exclusion and violence against various minor groups. Polls suggest that in the minds of the average Westerner, Christianity is associated with words like “homophobic” and “anti-science” more often than “love” or even “Jesus.” Now, you see a display where drag queens replace the figures of a Di Vinci painting of the Last Supper (if that is what is going on here—that is debated), and your first impulse is to say to yourself, “What will further Christianity in a world that no longer sees the value of faith anymore? I know—I have an ace up my sleeve—I’ll rant about it on Facebook!” Let’s pause and reflect on that one.

Is that really a strategy to defend the Christian faith? The organizers gave a half-hearted apology, but even if they somehow convincing gave some sort of “we are really, sincerely, sorry” routine, trying to close the proverbial barn door after all the animals ran out, I really don’t believe this would be a win for the Christian faith. Crying offense often only works when there is a loud outcry, and that means that attempts to shame the culture into respecting the Christian faith can still very much be a Constantinian strategy of power and privilege.

While we are at it, let’s think about who might be on your social media. Are there gay people on your social media? Trans folk? Queer folk? Perhaps not. Perhaps they don’t share that information. Ask yourself why? Can you ask yourself: What do you think they saw? They probably saw the fact that there are numerous other portrays of Jesus in our culture—the blasphemous portrays of Jesus by evangelical leaders in order to support Donald Trump, the rhetoric of “blessing Israel” invoked by some to justify the genocidal actions of the Israeli army in Gaza or just the myriad of other portrayals of the Last Supper in popular art—literally by almost every major TV series—that for some reason does not get people of faith worked up. Yet, Christians got upset over the one that had sexual minorities in it. What does that say? It says, implicitly, that it is not alternative depictions of Jesus that offend me; those people do. Let’s again pause and think about that.

Why did the artistic director of the Olympic ceremony do this? By his own intention, the director did not think he was trying to directly offend Christians. He says he was not even alluded to the Last Supper at all (which may just be an attempt to save face). It does seem that he was trying to portray something of the Greek mythic backgrounds of the Olympic, as well as what current French art is about: its capacity to be over the top, parody previous art pieces, making statements about inclusivity, etc. To that, I would say that if you designed a public portrayal of any religious figure in an unconventional way and did not think it would offend people (or if you really thought arranging the table that way with a centre figure like that would not be taken as an allusion to the Last Supper), you clearly did not think that through. If that is the case, as I said, I thought the display was in poor taste: Surely there could have been better—smarter—ways to celebrate French art and inclusion in a venue like the Olympics.

However, there is something profoundly indicative of our cultural situation where a classic Christian work of art is portrayed with members of a community Christians have often excluded as an act that says, as a culture, “we value inclusivity.” There is also something profoundly ironic about Christians getting angry at an art piece as an “attack” on their faith that fuels the very secularizing impulse that protects these displays in the name of inclusion and free speech. Let’s remember that the very reason, historically, that Europe started secularizing was because, after brutal religious wars, faith was no longer trusted as a discourse to build public flourishing upon. Again, let’s pause and think about this.

How should we defend the Christian faith? Let me suggest that it does not need “defending” at all. Such language implies Jesus needs to be defended, that the ones doing this are our “enemy,” etc. Is that kind of militancy the path forward? I have to ask: How did that go for Peter? What did Jesus do to the very person Peter tried to defend him from? If someone feels that there is a group of people that are the enemies of Christianity, the Christ-like response is to find a way to do good to them. Perhaps, in the name of defending Jesus we have inflicted our own wounds on others Jesus wants us to heal. That should be our reaction. If we are offended at someone representing drag queens at the Last Supper, perhaps the best “defense” is to ask ourselves, “What would it take for these people to feel safe enough, loved enough, understood enough, to be at our table?” Maybe then we will see what the Last Supper was actually trying to depict.

One with the Father: A Trinitarian Meditation for Father’s Day

Preached at Valley Gate Vineyard, June 16, 2024 (Father’s Day)

20 “I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. 22 The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. 24 Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory, which you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 “Righteous Father, the world does not know you, but I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made your name known to them, and I will make it known so that the love with which you have loved me may be in them and I in them.” (John 17:20-26, NRSV)

In this passage, Jesus prays for the church, and in this prayer, he speaks about his relationship with his Father, how they are mysteriously one: the Father in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the mystery of the Trinity that the Father is fully God, the Son is fully God, and also the Spirit is fully God, each showing that they are distinct persons and yet, they are one, one relationship in each other and through each other.

Now, I am a theology professor. I get to teach folk about this stuff, and sometimes, let’s just say, students are less than thrilled to dive into the tough stuff. Most grant that there is something about doctrine that is important. This thing called truth; we are all big fans, and so, the Trinity is worth a nod to being fundamental. Now, that can all sound well and good, but it is also quite mysterious and abstract, and who has time to understand all that stuff? Sure, the Trinity is important; sure, it’s fundamental but it is also kind of fuzzy.

That Father and the Son are one, the Son in the Father, the Father in the Son—what does it mean to be at one? What is the Trinity trying to teach us (especially today on Father’s Day)? Isn’t all this oneness talk just impractical abstract mysticism? Are we right to ask, as modern people, is all this really useful?

And while we are at it, isn’t talking about God as a father a bit sexist, a bit patriarchal? Again, we, as modern people, are we right to ask: why should I look to this ancient book called the Bible, a book that has caused wars, sanctioned slavery, suppressed science, and supported sexism? What could we learn from looking at this old language of God as a Father? What can it possibly say to our experience of our fathers and, for some of us, our experiences as fathers and how this relates to God?

One time, I was camping on the shore of Lake Erie with a group of friends for our friend’s bachelor party. Of the group of guys, most were from our Bible college, all except one, who Craig knew from his work. Upon realizing this, my Bible college mates inquired about whether he was a Christian or not. The guy merely said that he “just wasn’t all that religious.” Another guy in the group saw this as an evangelistic opportunity. The conversation frustrated the non-Christian guy. He left and went over to where I was sitting. He was visibly annoyed, and I cracked a few jokes to lighten the mood. We chatted there under the stars, glistening off the gentle waves of the lake. I was smoking a nice Cuban cigar. Eventually, curiosity got the better of me: “So, I am curious; what do you believe about God?”

“Well, I don’t know. My father brought us to church, and he was an alcoholic jerk. The stuff he did to my mother and me…” It went on something like this, and I had to interject.

“I asked you about God, and all you have said to me this whole time was about your Father.” The guy paused. He had not realized what he was doing.

I don’t recall the rest of the conversation, but it illustrated to me just how important it is to think about how we talk about God. How we talk about God is always bound up with our relationships with other people. You can’t do one without the other.

I asked about God, and he immediately associated that question with his father. Why did he do that? Why did he connect them subconsciously?

This association between God and our fathers is something perennial in the history of religion and it is deep in the Western cultural psyche.

Almost everywhere that people started thinking about God, they started associating with God the qualities of their parents, particularly their fathers, and for obvious reasons. Our parents are the source of our bodily existence, the ones who care for us when we are the most vulnerable, and so, their example forms some of our earliest feelings of safety, security, and provision. They form our earliest thoughts on what is ultimate in life, what is right and wrong, desirable or undesirable.

And so you have these analogies that appear both in the Bible and other religions: God is like a mother because God creates us like a mother birthing her child or sustains us like how a mother nurses her child. God is like a father in that since usually men are the physically taller and stronger members of the household, God is powerful and protective like a father. Because of this perception of power, the leader god in most pantheons in most ancient religions is usually a father-god, not a mother-goddess.

Now, if that is all that is, surely with changing times where both parents work, and gender stereotypes are frowned upon, then yes, referring to God as a Father is out of date. After all, women can be strong, and men can be nurturing, and so on and so forth. But is that really what is going on in the Bible? (I would point out to you that there are actually a number of references to God as female and motherly in the Bible as well if you look for them). But the bigger question is this: Is God really just a projection of what human relationships are like? Or is God ultimately beyond all that? If we think of God as a father, how does God show us what he means by that?

And on the other hand are we so different from ancient people? Our culture still experiences something that ancient times experienced: conditional love, absent love, broken love.

According to Statistica Canada, in 2020, there were 1,700 single dads under the age of 24. Also, in 2020, however, there were nearly 42 000 single moms under the age of 24. There were 21,000 single dads between the ages of 25 and 34 in Canada in 2020 where there were 215 000 single moms. Now, there might be lots of reasons and qualifications for these statistics (there are lots of single-parent households that are healthy and happy, don’t take this the wrong way), but it is safe to say that we still, culturally, are much more likely to be missing the love our of fathers on a daily basis than the love of our mothers. And, of course, that says nothing about the many double-parent families where the children have strained relationships with the parents they know.

We still face the same things as the ancient world, just in different ways. In ancient Greece, in cities like Sparta, if a child was not acceptable to the father, it was quite common, even expected, for the father to expose and kill that child. The father’s acceptance was conditional on whether the child was good enough and strong enough. For folks in this culture, they thought it was necessary: men need to be strong to fight wars. Weakness could not be tolerated.

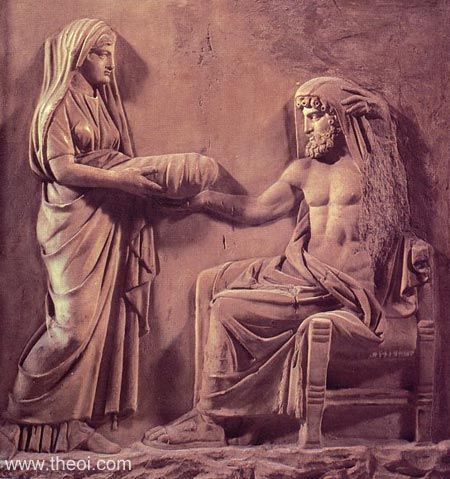

And this struggle to demonstrate one’s strength appears in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, there are two primordial Gods: the mother earth goddess, Gaia, and the father-sky God, Uranus.

They give birth to powerful monster gods called the Titans, the most powerful of which is Cronos, who resents his father’s rule and kills his father, becoming king-god. However, Cronos then becomes fearful that his children will usurp him, so he gobbles them up one by one after each one is born (Greek mythology is strange that way, I know).

However, one of his children, Zeus, is hidden from him and raised in secret, and it is Zeus who grows up to slay his malevolent father, assuming power to reign justly, at least for the most part. Zeus, however, in turn, fathers many illegitimate demi-god children, like Hercules and about 16 others in Greek lore, who grow up not knowing who their father is, often trying to do heroic quests to win Zeus’ approval.

Zeus slays his father, but he can never become a true father, it seems, in turn.

Deep in the religious consciousness of Greek religion is this conflict, this worry: If power is what makes a man, what makes a father, what makes a god, how can any son measure up? (But on the other hand, how can a father ever truly be a father either, if all he is obsessed about is power?) Or if the son is stronger, what is stopping them from replacing or usurping their weaker father, taking what their father has by force? And if that is the case, is Zeus all that different from Cronos? If power is what it means to be man, a father, or a god, then the more Father is like Son and Son like the Father, the more estranged they will be, the more they will fight, whether it is humanity to God or humans to one another. They cannot be at one.

I had this illustrated to me in one of the most profound movies on the effect of absent fathers I have ever seen. It is in the movie The Place Beyond the Pines. Ryan Gosling plays Luke, a motorbike stunt performer for a circus. He is a lone wolf, rough around the edges, a guy from the wrong side of the tracks. However, he learns that his ex-girlfriend had a baby, and it is his. He tells her that he loves her and wants to be for their child what his father never was: a provider that will come through for them. However, he admits that working for a circus does not pay well. He can’t afford the things he believes a father should be able to afford for his child. His girlfriend, however, just assures him that being there is enough. But Luke is afraid that he will be inadequate, just like his father was to him. So, his buddy tells him that if he wants to be a real man and provide for his family, he has to use whatever skills he’s got to do it. For him, it is his exceptional skills on a motorbike that could be used for something else: robbing banks and alluding to cops. Luke, in desperation, agrees. He robs the bank and speeds away from the cops on his bike almost effortlessly, and he is able to take that money and buy a crib and clothes and baby food and even take his family out on a dinner date. However, he realizes he will need more, so, he tries a double robbery, but it goes south, and in the mess of trying to allude to the cops, one cop, Avery, played by Bradley Cooper, shoots him and kills him, even though Luke is unarmed.

At this point, the movie shifts the main character from Luke to Avery. Avery, we learn, is a workaholic cop, being a cop is everything to him, despite him having a young family. For Avery, being a man means being a good cop. However, Avery is stricken with guilt over killing an unarmed man, something a good cop would never do. but Avery’s fellow cops cover up his fatal error, but this does not make him feel better as he learns just how corrupt some of his fellow cops are.

Moreover, he learns that Luke had a son about his son’s age and that the reason why Luke turned to crime was to provide for him so that his own son would be proud of him, the same reason Avery joined the police force, to make his dad proud of him. Because of the guilt, Avery can no longer stand to be around his own son, unable to be a father to his own son, knowing how he took some other boy’s father, punishing himself by denying himself a relationship with his own son.

The movie concludes years later. Avery is running for office, a workaholic relentlessly working for government reform, but doing this deep down to make hopeless amends for killing Luke. However, along the way, his son and Luke’s son, both teenagers now, both wayward and troubled from not having a father figure, meet and realize that while initially hate each other, Luke’s son sees the possibility of enacting revenge—they realize that they are the same: one had their father taken by the other, but the other never had his father to begin with, despite them living in the same house. And yet, ironically, sadly, the two of them show signs of becoming just like their fathers, one a reckless wonderer, the other a perfectionist.

The more Luke resented his father, the more he became like him, and this conflict, this estrangement continued from his father to him, but now from him to his son, who, just as ironically, ends up just like him. If our value as men, sons, and fathers is equated with our performance, we will not be at one with each other.

Think about that yourself. For many of us, we had good relationships with our fathers, but perhaps you did not. How has that affected you? Will we choose to see how our fathers are in us, whether this is good or bad?

Well, again, we like to think that we are better than all this ancient barbarism and mythology, but we are not all that different. The same human nature is within us, and there is the same realization: with so many of our relationships, especially ones as important as the ones between parent and child, we are not at one.

And there is an irony to all this with religion: We as a secular society believe that now that we are smarter, more educated, more technologically advanced, more politically organized…more powerful, we don’t need God. Isn’t secular society just one more attempt to kill Cronos all to end up just like him.

“God is dead, and we have killed him,” said the philosopher Nietzsche, declaring that to live in the modern world was to live with a rejection of God as an idea that was useful and meaningful to life. To live in a secular world is to live in a world that has pushed out God, religion, and even objective morality, all in the name of our own will to power. But even Nietzsche worried whether humans were indeed able to live without God.

We live, as George Steiner once said, with a “nostalgia for the absolute.” We live with an awareness that something is missing, something is absent, and for many of us, we live our lives trying to fill that void with something else, whether it is work, achievements, money, sex, or just mindless consumption and entertainment, whether it the socially expectable kind like Netflix or video games or ones less so like drugs.

I had this connection between God the Father and our fathers in a secular world illustrated to me in one of my favorite novels of my young adult: Fight Club.

Fight Club, for those who don’t know this cult classic, is a story about a man who works a meaningless job for a greedy company. His life has no purpose, so he finds himself unable to sleep, passing the time by ordering useless products from shopping channels. However, he meets a man named Tyler Durden, who convinces him to punch him one night after a few beers in order to make him feel better. The man does, and the two start sparing, punching each other. It feels therapeutic for them, so they start up a fight club in the basement of that bar.

Tyler Durden and the main character talk about their past and about God, and both realize that they had fathers walk out on them, and they feel like this is a reflection of what God is like, too. Other men join this fight club, fighting others as a way of expressing their rage over their meaningless lives. Tyler names their struggle in one monologue he makes:

“Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering…an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables—slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy [stuff…he says something else here] we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man: No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war; our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day, we’d all be millionaires, movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Other chapters of these fight clubs start opening across the nation, and Tyler Durden starts manipulating them into cult-like cell groups, sending the men out on missions to vandalize corporations, with the grand scheme of blowing up the main buildings of VISA and other credit cards and banks, effectively resetting civilization. Tyler believes that he is some kind of messiah figure for himself. The narrator explains Tyler’s motives this way:

“How Tyler saw it was that getting God’s attention for being bad was better than getting no attention at all. Maybe God’s hate is better than His indifference. If you could be either God’s worst enemy or nothing, which would you choose? We are God’s middle children, according to Tyler Durden, with no special place in history and no special attention. Unless we get God’s attention, we have no hope of damnation or redemption. Which is worse, hell or nothing? Maybe if we’re caught and punished, we can be saved.”

Do you know people that say they don’t care about God but are living like they are desperately trying to get God’s attention?

And in a secular world, where we live either ignoring God or feeling God’s absence, as well as living in a world where masculinity, our worth as fathers, is so often defined by power as well as the money we make and the stuff we own or achieve, relationships like the ones between child and parent will be marked with conditions and expectations, caught in this vortex of conflict, competition, and estrangement.

If God is not love, no matter whether we run for God, ignore him, disbelieve him, or hate him—if God is not love, we will end up just like him: unloving ourselves.

I say all this to say that there is a longing deep in the heart of humanity, a longing for meaning and purpose, for acceptance and love, and this longing is symbolized in God the Father so often because of the role our fathers play, whether for good or ill, and it is a longing for oneness.

We have to ask a question fundamental to our future as humans: who is this God that we so often look to as a father? Does God care more about ruling unquestioned than loving his children for who they are? Is God the kind of God that will reject us if we don’t measure up? Will God ignore us if we ignore him? Is love conditional? Is oneness possible? Oneness between God and humanity and humanity with each other?

Well, the story of Scripture tells a different story of God as Father. To confess Christ is to attest to how we have found ourselves in a story where the Creator of all that is chooses to create people in God’s image and likeness. Image and likeness was a way of talking about one’s children. A child is in the parent’s image and likeness and so, God makes all people to be his children, making them with dignity, designing them to reflect his character of love as the way they can most authentically be themselves.

This God reveals himself in history, calling Abraham out of his father’s household, out of idolatry, and into redemption, promising to bless and protect him.

This God led the Israelites out of Egypt, a people oppressed and enslaved under idolatrous tyranny, and God told them that out of all the human family, Israel is to be his firstborn, a nation that has a unique purpose in reflecting God to the nations around it.

This God says God is One, the I am who I am, the living God, and this One God longs to be one with us.

This God says that he is like a father. However, even more than that, God is the perfect father, and God, as this perfect father, beckons us home when we have rebelled against him.

And so when we look at the narrative of the Bible, we see this One God revealing who God is in this pursuit of being at one with us in a way that mysteriously takes on—for lack of a better word—different dimensions to God’s self: the God who is beyond all things, infinite, transcendent, and almighty, but is also the root of all existence, the breath of life, the presence of beauty, one in whom we live and move and have our being, the movements of love, known as Spirit.

As the narrative shows, these dimensions relate to one another. God sends his messiah, the king, but a king that is more than another human king; he is God’s only begotten Son, one with the Father. There is no conflict between Jesus and God because they are fully one with each other to the point that when you look at Jesus, you see the visible image of the invisible God. God is not a distant God. He is with us.

The Father sends the Son, Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly enfleshes the presence of the God Israel worshiped but also fulfills the longing for righteousness, this reconciling oneness with all things Israel was called to, and Jesus does so through sending the Spirit.

This story clashes with human sin, however, and it comes to a particular intensity when people reject Jesus’ invitation to step into the oneness of God. John says at the beginning of his Gospel: “The world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him.” We know how this story goes.

Jesus died on the cross, executed by an instrument of imperial oppression orchestrated by the corrupt religious institution seeking to preserve its own power, but also betrayed by the ones Jesus was closest with, his own disciples and his friends. The cross discloses the tragic depth of our tendencies to refuse to be at one with God and others, even when literally God is staring at us face to face.

But it is in these dark moments that God showed us who God is.

For Jesus to die one with sinners, yet one with the Father, reveals God’s loving solidarity with the human form—our plight, no matter how lost or sinful. God chooses to see God’s self in us and with us, never without us. God chooses to bind himself to our fate to say, “I am not letting you go.”

To be a part of the family of God is to trust in Jesus Christ; it is to remember that in these moments of condemnation, we have been encountered by the presence of the Spirit, a love that invites us to see that we are loved with the same perfect love the Father has for his own only begotten Son. The same love that God has for God in the Trinity, God has for sinners, for you, and for me. God is not going to give up on us.

Paul says it this way, “If we are faithless, God remains faithful.” Why? “Because he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim. 2:13).

That is the truth of the Trinity. Trust this. God has made a way for him and us to be one as he is one.

And if God is like this, this suggests ways our relationships can be healed and improved.

Can this propel us to love our fathers more, not merely for all that they have done for us (or have not done for us), but to love them for who they are, to love them as God loves them, to see ourselves in them and reckon with that, with thankfulness, with forgiveness, with gratitude and grace?

Can this change how we think about our own children? If God sees himself in us, can we empathize more with them, seeing ourselves in them, rather than just making sure they shape up to what we expect? To be there for them, love them for who they are, and the journey God has them on.

And God says, “May they be one as we are one.”

Let’s pray…

Justification in Diversity

Preached at Bethany Memorial Baptist Church, Sunday, January 30th, 2022, for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity.

14 What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if you say you have faith but do not have works? Can faith save you? 15 If a brother or sister is naked and lacks daily food, 16 and one of you says to them, “Go in peace; keep warm and eat your fill,” and yet you do not supply their bodily needs, what is the good of that? 17 So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.

18 But someone will say, “You have faith, and I have works.” Show me your faith apart from your works, and I, by my works, will show you my faith. 19 You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder. 20 Do you want to be shown, you senseless person, that faith apart from works is barren? 21 Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? 22 You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was brought to completion by the works. 23 Thus, the scripture was fulfilled that says, “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” and he was called the friend of God. 24 You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. 25 Likewise, was not Rahab the prostitute also justified by works when she welcomed the messengers and sent them out by another road? 26 For just as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is also dead. (James 2:14-26, NRSV)

When I was young, I attended a little Bible camp for many years. I loved it. Set out in the woods, it was always the highlight of my summer there: the sports, the crafts, the campfire with singing and snacks afterwards.

But most importantly, as a Bible camp, they did bible stories. At the campfire, they would do dramas of different bible stories, and one person always told a story of a famous Christian like Dietrich Bonhoeffer or Nickey Cruz. Those stories left a profound impact on my faith as a young person. It was at this camp, really, where my love of the Bible began.

So, when one of the leaders talked about baptism, inviting anyone to be baptized if they professed to believe in Jesus, I naturally came forward, all to have myself abruptly halted. “I would like to be baptized,” I said. However, the leader simply said, “Spencer, I can’t baptize you.”

I said, “Why not?”

He answered, “Because you don’t go to one of our churches. I can’t baptize you in good conscience unless I know for sure that you will go to a biblical church after.”

Now, for the record, I attended a Christian and Missionary Alliance church at the time, one that prided itself with being bible-believing. His words shocked me.

I remember protesting this with him: “Are we not all Christians here? Don’t we all believe in Jesus here?” His response was a bit sheepish, but his answer was, “Sorry, Spencer, that is not enough.”

That experience, as I think of it, was really the first instance where I witnessed exclusion within the body of Christ for myself. It was the first moment I became aware that just because we are all Christians, who believe in Jesus, that does not mean we all treat each other as Christians.

And as you listen here this morning, think about is yourself: what was the first instance where you felt demeaned by another Christian about your Christian beliefs? Or perhaps, can we be challenged to think about how we might have been the ones who did the excluding?

This week has been if you did not know, the week of prayer for Christian unity. It is a week where Christians pray in repentance for how we have so often divided the Body of Christ based on our faith convictions: Catholic against Protestants, and of course, Protestants against other Protestants, even Baptists against other Baptists in our own churches.

It is kind of funny that we put together this preaching schedule, John and I, just going passage by passage. Interestingly enough, this passage takes place on the week of Prayer for Christian Unity. I say “funny,” you might call that providential too.

James challenges us to live our faith, that we are rendered just by what we do. And we will see, the language of this text here is very different from the words of Paul on justification, which he says is by faith. As we will think about this morning, this text challenges us to live our faith but also live out our beliefs in the midst of the diversity of Christianity in a Christ-like way.

1. Seeing Diversity

First, I want to tackle what seems like a point of diversity and tension in the Bible. James calls us to live our faith. He puts it in pretty strong terms. He says, So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead… You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. Here a scripture says you are justified by works.

Now, Paul in Galatians says, this: …a person is justified not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ. And we have come to believe in Christ Jesus, so that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law because no one will be justified by the works of the law.

One says justification by faith, the other justification by works.

Martin Luther used this teaching from Paul to found Protestantism (and we are all Protestants because of him, by the way). Five hundred years ago, he protested the Catholic Church and its corrupt practices. Martin Luther saw how the Church was using sacraments to enforce their power, saying if you comply with this, if you pay money to us, we will give you forgiveness, and you or the loved one you pay for will be saved. Luther called this works righteousness, making salvation conditional on what you do. He saw what Paul was saying in his own day as applicable to his: Jewish Christians in Galatia sought to make Gentiles accept laws like circumcision to be members of God’s people, and so, the Catholic church was making certain things the requirement to receive grace. Luther’s protest against this succeeded, recalling the church to what the Bible taught, sola scriptura, by scripture alone, and the rest is history.

However, there was a kind of flaw in Luther’s argument. He argued for sola scriptura, but there was a scripture that did not quite conform to what he said. James says no one is justified by faith.

Martin Luther saw this passage, and he hated it. He called James the “epistle of straw” and did not think it ought to be in the Bible. It is ironic that a Reformer that wanted things to be biblical oddly did not want to listen to this Bible passage. Have you ever done that? Many of us are guilty of picking and choosing.

Why did he do this? I suspect Martin Luther assumed the Bible to be uniform. The Reformation as a whole certainly believed that if you just trusted God and read the Bible, one biblical view of things would always emerge with the Spirit’s help.

Well, as the years following the Reformation showed, that did not happen. One after another, groups like Anabaptists and Baptists, Methodists and Pentecostals all looked at biblical texts with a passion for living out the Bible and came to different conclusions, splitting off from their previous group.

And what happened when they did this? Their tendency was to think, “Aha! I have the Holy Spirit, and I have it right. God revealed to me the true apostolic pattern that has been lost for centuries, and all those other Christians must not have the Holy Spirit, and they need to listen to this discovery I found, or they must be evil.”

Well, when they did not all agree, they fought and, in some cases, killed each other. Reformers hated Baptists and would take Baptists and drown them in rivers, giving them what they felt was their real baptism, terrible things like that.

The result of these religious wars and violence is that Western society saw Christians fighting over doctrine and said, “I don’t think we can build just laws on what they believe.” In other words, if we lament the loss of Christianity in the public sphere, if we lament that we live in a secular society in Canada, I don’t think we need to wonder why. It was our fault.

It all comes down to this tendency that Christians have not known how to manage, this notion that two sincere believers can come to the same text and conclude very different things. We don’t know what to do with that, other than by treating differences as dangerous:

You are either too liberal, too conservative, too traditional, too informal, too emotional, too rational, too this or too that. We are quick to label and dismiss, or worse, exclude.

In my experience, the two primary things Christians have fought about in recent years are styles of worship and ethics of sexuality. And if you cannot come to grips with the fact that there are good believers on either side of a debate, trying to navigate it because they love Jesus, we are only furthering this 500-year-old problem.

We have not been good at dealing with diversity. When we see it, we divide. To date, there is somewhere in the ballpark of 50 000 denominations of Christianity, who have all, more or less followed this tendency.

But what if diversity is not all bad? What if diversity is not always a cause for division? What if there is something about our faith that is naturally diverse? What if there is diversity in the Bible?

I think these texts have something to say about this. Some scholars have suggested that these two passages in Paul and James could reflect two views in what was really the first theological debate of Christianity. What is the role of works? What is the role of faith and the law? James and Paul answer it differently.

It is interesting that James quotes the exact same texts from the Old Testament as Paul does in Galatians, referring to Abraham and Isaac, and they interpret it two different ways. Are we witnessing here the records of two Apostles differing about their faith in Christ?

Of it is, that raises some interesting notions for our faith. We like to think that early Christianity was perfect, that they agreed on everything, that they miraculously never fought, never disagreed, never had to discuss and debate. They all just supernaturally knew what to believe about everything. Well, if we read the book of Acts or other books in the New Testament like these, we just know that is just not the case (and frankly, I for one find it oddly comforting to know just how weirdly messed up the church at Corinth was).

And if you look at a book like John or Mark, in particular, you will see that in the early church, there were different ways to tell the story of Jesus.

The Bible, the inspired Scriptures, contains diversity: different ways of thinking about Jesus and following him that the early church did not ultimately see as bad. Maybe God is trying to give us a hint with that.

And when it comes to a disagreement like the role of Jewish laws for the church that now includes Jews and Gentiles, Paul and James had to come together with the rest of the church, as it shows in Acts 15 and work it out. They had to come to terms with their differences. Now, we don’t know if the book of James was written before the events in Acts 15 or after, but the fact remains: in the Bible are two Apostles speaking quite differently about their faith in two different letters of the early church, which the church today draws inspiration from. Again, I think God might be giving us a hint here. Diversity is to be expected, and what we do with that is really the mark of what it means to follow Christ.

Now, the question is, how far do they actually disagree? For instance, there were groups in the church that did not believe Jesus came in the flesh and did things that harmed fellow Christians, and John says in his first epistle that this is too far. Clearly, there are limits to diversity, and we need to think about those.

When we look at the history of the church, we see the creeds of the faith offering decisions that I think provide helpful standards, classic summaries of what Christians hold as central. That does not solve it all, however. For instance, the Apostle’s Creed says nothing about how the church is to confront modern racism or climate change, but they are all part of the task we have as the church of discerning wisely together.

And, on many matters, there is a kind of range of views being worked out that is well accepted amongst Christians. And on this matter, as it goes with many theological debates with Christians, what sounds like a deep divide between how we talk about our faith, is, in reality, not that big of a difference.

I remember one time in seminary, listening to two students talk about eschatology (the end times) over soup in the cafeteria. One student said that when they looked at the biblical evidence, they just did not see a premillennial rapture. They saw something more like an amillenial kingdom. The other was mortified, and I remember them saying: “If you don’t’ believe in premillennial dispensationalism, I don’t know how you can be in the truth!” (Now, if you don’t know what those terms are, consider yourself spared)The important thing that struck me was just how ridiculous this was: I am pretty sure both still believed that their hope was Jesus.

I think something similar is happening in Paul and James, just in different contexts: Paul is going after Judaizers that believed you need to obey the whole law, including getting circumcised, in order to be one of God’s people. However, Paul very much believes that we need to obey the law of love, love our neighbours as ourselves, and live in a way that manifests the fruit of the Spirit.

And James, here it seems, is not interested in ritual laws like the people in Galatia are worrying about. His concern here is with the poor. If we believe that God loves the poor, if God loves anyone really, we will do something to help. And if you believe something, he says, we ought to live it, namely, just like Paul, by following the “royal law:” the law of love, love your neighbour as yourself.

So, James goes after a faith that does not do anything to help, whereas Paul goes after a view of the actions that make people believe they are better than others.

Yet both, however, are committed at the end of the day to humbly trusting Jesus and following him.

Both are committed that at the centre of the Christian life is living out love.

Ask yourself, if you have had a debate about your beliefs as a Christian with another: what are the things you hold in common? Are you really so different?

An old motto of Christian unity is this: In the essential things, unity; in the non-essential, liberty, but in all things, charity. Let that be your guide.

2. Living Reconciled Faith

So, we need to take James’ point: Faith is something we need to live. And when it comes to diversity, we need to live out Christ’s reconciliation. And if that is the case, we have not done in our works what we often believe.

Paul says in Ephesians 4:4-6 says, There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope of your calling, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is above all and through all and in all.

James might get us to look at that and ask, “Do you really believe that?”

James says You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder. The real difference is that we are willing to act on this.

Do you really believe that we are one?

Do you really believe if someone is baptized in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, they are your brother or sister in faith? Even if they are a Catholic, even if they are a liberal, or even if they are a fundamentalist? Or whatever group in Christianity is the group you tend to have very little patience for. They share in this oneness, and we need to live accordingly.

It is one thing if we all call ourselves Christians. James might say. It is quite another whether we actually treat each other as Christians.

The opposite is a dark path of believing only people like us are the true believers, and everyone else is wrong, or worse, evil, and living out our days in an ever-shrinking echo chamber of our own making.

This does not mean that we compromise on what we think is true and good. It does not mean that just because someone calls themselves Christians, we give them a free pass to believe anything they want.

I say that as a person that had to leave the Baptist denomination my grandfather helped found because I became convicted that God’s kingdom means equality between men and women and that women should be ordained. After I was given a threat that if I kept speaking about this, I would lose my funding as a church planter, I realized I had to leave for a denomination that did support women’s equality.

And if you have ever had to leave a church family, you will know these moments are painful. We have to be wise on what we take our stands on and be diligent to be healers of the wounds that mar the body of Christ.

There are things we need to take a stand on, but that does not mean seeing those who differ from us as evil or stupid, and hopefully, we can navigate these tensions with gentleness, patience and peace.

Other times, our differences should not get in the way of Gospel work. I remember when I worked at a soup kitchen. This ministry attached Christians from all different strips. And it always struck me that when we centred on the task at hand of helping those who were in need, our differences always felt smaller.

So, I will repeat this, realizing that Christianity is a diverse place does not mean we compromise on the truth, but it does mean we go about the truth a different way.

It might mean giving the benefit of the doubt before judging.

It might mean having some sense that we are just as fallible, and we need to listen.

It might mean taking steps to be patient and forgiving.

It might mean being tolerant and focusing on our shared tasks of caring for others.

All of this speaks again of what James is challenging us with: we need to put our faith into practice. We need to step up and do the work of listening and discerning, confessing and repenting, forgiving and reconciling.

It means treating people like family, knowing that God is bringing together all peoples into one family through what Jesus Christ has done for us.

3. Witnessing the Spirit in Unity

Only then will we welcome differences not as dangerous but as a reflection of what the Spirit started doing at Pentecost, bringing people together as members of many tribes and nations, languages and ways of thinking, into God’s family.

Can we allow ourselves to be open to this?

I remember one event where the Spirit moved in this way. It was at a unity service for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity seven years ago. I was pastor of First Baptist Church of Sudbury. Our church participated in the ecumenical service for several years before that, but I suspected we did that as some way of showing the other churches just how much more biblical we were than them. Well, over the years, that didn’t quite work out that way. Members of our church got to know members of the Catholic, United, and Anglican churches, and different members attended each other’s events. In a small town like Garson, that meant we all started saying hi to one another at the grocery store and being neighbourly to one another. We all intuitively started thinking we were not so different after all. Maybe we do have something in common.

Well, that unity service, held at the catholic church that year, it is like this all bubbled up. I remember the one pastor gave a great monologue as if she was the woman from the well. And people were asked to come up in pairs to a pool of water. They were asked to say words of repentance, acknowledging how we have harmed each other, the body of Christ, and then make the sign of the cross with water over the other’s forehead.

I remember sitting there with the other pastors when I looked back and saw people beginning to break down and cry. Others were hugging, saying, “I’m so sorry. I am so sorry.”

I can tell you that I have never seen the Holy Spirit move in a room like I did that service, and it happened by a willingness of those in the room to repent and realize the people in this room, despite different traditions of Christianity – were all family.

Bethany Memorial Baptist Church, how might we see the Spirit move among us today if we are willing to reconcile with other brothers and sisters in our Christian family? What might our witness be in this broken, fragmented world?

What would the Spirit do if we are willing to let go of our arrogance, be willing to listen and learn, but also go forward together to care for one another and serve those who need help in our communities? I am excited to see what the Spirit will do.

Let’s pray:

God, our Father, who has brought us all together as a family through your son Jesus Christ, have mercy on us and forgive us for all the ways we have not loved our neighbours as ourselves, and especially have not treated fellow Christians as family.

Let your Spirit move amongst us with a spirit of repentance and humility, a spirit of service and solidarity. Show us ways we can come together and live our faith in the Good News.

In Christ’s name, amen.

The First Christmas: An Unbelievable Story about our Unbelievable God

The Adoration of the Shepherds by Guido Reni (c 1640)

We have all heard the Christmas story before.

The Christmas story is the story of a baby born miraculously and mysteriously to a virgin mother.

About a nobody girl named Mary, who saw the announcement that she would be the mother of the messiah to be the greatest privilege of her life, despite its meaning she would be ostracized perhaps the rest of her life, since she was not married

It is the story about a good and merciful man, named joseph, who when he heard that his fiancé was pregnant and he was not the father, he could have subjected her to disgrace and even had her stoned in the culture, but moved with compassion, simple was going to dissolve the marriage quietly.

A man that was reassured by an angel to marry the woman, and that he would be the legal father of the savior of the world.

It is a story set to the back drop of God’s people conquered and oppressed by a massive empire, ruled a tyranny Emperor who claimed himself to be the Son of God.

It about this little unlikely family having to travel miles through storm and sand to the town of Bethlehem to be counted by order of the Emperor Augustus.

It is a story about this family who upon returning to their own hometown found that no one wanted to give them shelter for the night. No family wanted them.

It is a story about the king of heaven being born in the muck and mire of a barn.

It is a story about good news announced by angelic hosts to lowly shepherds, forgotten in the wilderness, tending their sheep.

It is a story about wisemen following stars, fooling a local corrupt ruler and coming to worship the messiah child with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

It is a story about an escape in the night as Herod sent out guards to kill the children of Jesus’ age, trying to stop the potential usurper.

And so, this is a story about miracles and the messiah, about faithful servants and faithful spouses, unplanned pregnancies and ancient prophecies; it is about shepherds and tyrants, about journey and escape, about humility and royalty, oppression and hope.

This story is the first Christmas. It is the story. It is the most important story. It is the story of all our salvation. Our salvation began to be accomplished in history on that day, in that stable, in that dirty manger, to that poor Middle-eastern couple, two thousand years ago.

It is the truth that God is now with us: the incarnation. The infinite God dwelling with us mortals.

It is the truth about God’s rule. The messiah Jesus shows how God rules: he chooses the lowly; he chooses the poor; he chooses the unworthy, the forgotten, the unlikely. He prefers them to the powerful, the rich, the proud, and the oppressor.

It is the truth about forgiveness. Jesus wasn’t just the king of the righteous. He didn’t just love the deserving. He also loved sinners. In fact, he died for the people trying to kill him. He died for Emperor just as much as the shepherds. He died for King Herod just as much as the wise men. He died for the criminal and the terrorist just as much as he died for you and me.

The Christmas story is the truth about God’s fundamental character of love and compassion, about God being born in our form, identifying with our plight, binding himself to our fate, all to say that nothing can separate us from his love.

Immanuel: God is with us. He is not against us, he is for us. He gave us his son. He gave us himself.

It is also a difficult story to believe, too isn’t it? We live in a world of skepticism. It seems that usually about this time every year someone publishes an article, proclaiming their modern brilliance at just how unbelievable the Christmas story is.

Angels don’t exist. Miracles don’t happen. Virgins don’t have babies. Stars don’t give travelers directions. Gods don’t reveal themselves. It is simply an unbelievable story.

It’s preposterous; it’s impractical; it’s too spectacular; it’s too amazing. Things like this just don’t happen.

But our culture’s skepticism over the things of God – whether it is the possibly of miracles or the fact that God could indeed reveal himself – pays a high price.

Skepticism against the Christmas story is skepticism against hope itself.

We live in an apathetic age.

Wars can’t be stopped. Poverty can’t be solved. Politicians always lie. Life is always unfair. Marriages never work. Churches never help. God isn’t there.

There is no life after death, and ultimate no reason for life before it.

Right and wrong, good and evil, hope and tragedy, these are just creations of the human imagination with no real anchor in reality.

The world is not getting better. In fact, it is getting worse and to be honest, most people would think we are not worth saving.

Forgiveness? Hope? Love? Goodness? It’s preposterous; it’s impractical; it’s too spectacular; it’s too amazing.

It is unbelievable.

Perhaps the Apostles passed along this story not because they were primitive, but because they were just like us.

They lived in a skeptical age. Tyrants stayed powerful; peasants stayed poor; lepers stayed sick; women and slaves stayed property; the dead stayed in the grave; and there is nothing new under the sun.

…Until Jesus showed up. Perhaps the reason the Apostles passed along this Christmas story is precisely because it was unbelievable. Unbelievable yet true.

This is a watershed moment in history, a game-changer, a paradigm-shifter, an epiphany, an event.

God showed up. Hope showed up. Goodness and mercy and forgiveness showed up. Nothing like this had ever happened in their time. Nothing like it before or after. Prophets had foretold this, but who could expect it happening in this way?

Perhaps this story is true in all its remarkable, exceptional, unbelievable, beauty.

We can ask, just like Mary, “How is this possible?” And the angel’s words are just as true today as they were two thousand years ago: With God all things are possible.

With God all things are possible.

If we grant that, this story starts making sense.

Good does triumph over evil. Love does triumph over hate. Forgiveness does triumph over hurt. Peace does triumph over violence. Faith does triumph over idolatry. Hope does triumph over despair.

These truths are not the delusions of us human bi-pedal ape-species with an overgrown neo-cortex.

The deepest longings of the human heart, the groaning of the soul for a world without hunger, sickness, sin, death, and despair – as unrealistic as that sounds – that yearning knows this story is true the same way our thirsty tongues know that water exists.

Its real. Its possible. It is out there. It is here: in Jesus.

The only left to do with this story, when we are done pondering it and puzzling is to trust it.

Can you tonight trust this unbelievable story? Can you trust that with God all things are possible?

Can you trust that your life is not just there without value, but it is a gift, it was planned and made by a God that sees you as his child?

Can you trust that the wrong in your life, the sins we have committed that no excuse can defend has been forgiven by a God that knows you better than you know yourself and sees with eyes of perfect mercy?

Can you trust that God has come into history, has shown us the way, has died for our sins, and conquered the grave?

Can you trust that God can set right all that has gone wrong as we invite him to renew our hearts, our minds, our souls and strength, our relationships, our job and family, our past and future, our communities and our country?

Can you trust that this Christmas story about God’s miraculous power, his unlimited compassion, his surprising solidarity, can be shown to be true this night just as much as it did then? In you, in the person next to you, in this church, in this town.

We give gifts at Christmas time as a sign of God’s generosity, but do we look forward to God’s gifts to us each Christmas?

Do we look for the gift of renewed spirits?

Do we look for the gift of transformed hearts?

Do we look for the gift of forgiveness of past hurts?

Do we look for the gift of reconciled relationships?

Of new freedom from guilt and shame, from hurt and hatred, from addiction and despair, from materialism and apathy.

What gifts are we going to see given from God’s spirit this Christmas.

Perhaps it will be like what happened to Nelson Mandela (just one story I read about this week about how the truth of Christmas changed someone in remarkable ways). In South Africa where Blacks were segregated off from the privileged of White society, Mandela as a young man advocated armed uprising and was imprisoned for life in 1962.