Tagged: Weakness of God

The Humility of God: Palm Sunday and How the “Weakness of God” Saves Us

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion!

Shout, Daughter Jerusalem!

See, your king comes to you,

righteous and victorious,

lowly and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

I will take away the chariots from Ephraim

and the warhorses from Jerusalem,

and the battle bow will be broken.

He will proclaim peace to the nations.

His rule will extend from sea to sea

and from the River to the ends of the earth. (Zechariah 9:9-10, NRSV)Zachariah’s Vision of a Lowly King

If you were to skim through the Bible, you would not be hard-pressed to find some grand depictions of God.

Jacob in the Book of Genesis has a vision of God when he is asleep at Bethel. God is at the top of a heavenly stairway, where angels are descending and ascending. It’s spectacular.

In the Book of Second Chronicles, the prophet Micaiah has a vision of God seated on his throne, and again, angels attend to him in a magnificent court.

Or, think of the vision of Isaiah where he sees God the king in the temple, and the train of his robe fills the temple, smoke and thunder bellow, and six-winged angelic seraphim continually praised God, saying, “Holy, Holy, Holy.” It’s amazing.

Or, you could go to prophet Ezekiel, who has a vision of God on a flying throne of sorts. This vision has this throne laden with gemstones, carried by four surreal angelic creatures, each with four heads glowing and spinning. It’s remarkable.

Or you could go to the prophet Daniel, who has a vision where God stands on the clouds above all the powers of the earth in judgment, and he is called the ancient of days.

God in these visions is majestic, all-mighty, holy, transcendent, and awesome.

These visions were given to these prophets in times of turmoil to remind the people that God is beyond their circumstances. God is of a magnitude that makes all our problems look small.

All of these depictions are true and good and comforting, but that is not what Zechariah does. The passage I just read is a prophecy from Zechariah, spoken to the people during a time of great chaos as well, but the vision takes a very different path to comfort the people than these other ones. Zechariah, in other passages, has similar descriptions of God to the ones we just listed, but here it is different. This one doesn’t give us the lofty vision.

And this morning, I want to reflect on a quality of God that we probably don’t think as much about: the humility of God, the lowliness of God. When was the last time you thought of God as humble or lowly? It doesn’t seem like something God should be.

Zachariah lived more than 500 years before Jesus, and he gives visions in his book that are meant to warn the people of their complacency but also comfort them with hope. Like most prophetic books he begins very heavy on the words of warning but moves into the final chapters with words of comfort, which is where this one happens.

So, what do these visions pertain to? The people have returned from being exiled, and their land has been decimated. Life is hard and uncertain. Enemies prowl the countryside to raid innocent people. There is lawlessness in the land. The great empire of Babylon has fallen, but the Persian empire now reigns. Persia is more tolerant of the Jews, but this is still a far way off from the visions of restoration the earlier prophets spoke about. And so, the people are wondering where is God’s kingdom? Why isn’t God showing up in power and glory, in fire and fury? When is God going to restore King David’s rule? Why isn’t God appearing like he promised to crush our enemies, make them pay, and make things better? Isaiah promised a day of peace so extraordinary cosmic that one day the lion will lay down with the lamb. When is that coming?

Zechariah’s answer to all of this is somewhat strange. God is coming; he is sending his king, his messiah representative, who will bear this redeeming presence perfectly. What does he look like?

See your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, but lowly—humble—and riding on a donkey.

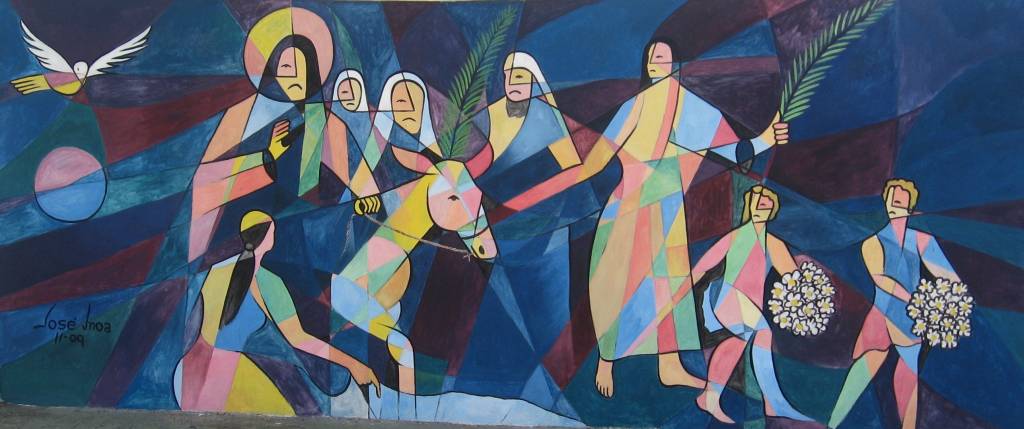

Oh, okay? And this is the image Jesus uses when he rides into Jerusalem, praised as a prophet and messianic hopeful by the people. The people expect a mighty king, riding in on a stallion in armor and gleaming sword. The people cut palm branches, which were the symbol of the house of the Maccabees, legendary warriors and freedom fighters from Israel’s history. The people are thinking, finally now that day has come.

Yet, Jesus invokes this passage from Zechariah by choosing to ride in on a donkey: Humble, lowly. You can only imagine this might have been a bit confusing for some of the crowds: this guy?

I mean it is sort of like a world leader strolling into parliament driving a rusty, old delivery van. Somewhat underwhelming, you might think. And let’s be real: that is not what we want our leaders to do. We want the motorcade of limos and police escorts driving in perfect synch with lights flashing and little flags on the aerials. We want the expensive suits. We want people behind them also in suits, wearing sunglasses and eye pieces, concealing body armor and pistols. We want the displays of power.

Because let’s face it, when the going gets tough when my place in the world feels threatened and I feel like I need protecting. I don’t want a pushover in my corner.

If things get tough, who do I want on my team? Do I want Clark Kent, the mild-mannered reporter who bumbles about, or do I want indestructible Superman flying in in his red cape and laser vision?

Do I want the wussy Prince Adam, or do I want He-Man?

Do I want Popeye before he eats his spinach or after?

The choice is kind of obvious. Or at least it certainly seems so.

But a scan through world history might give us some caution. Just how often are the mighty on the side of the needy? Just how often are the rich on the side of the poor? Just how often are those of status on the side of those who are marginalized?

How often are the powerful good? Not very often.

Zechariah’s description almost sounds contradictory: Righteous, victorious, lowly. It feels like history usually only grants one of those at a single time.

You get one or the other. After all, “nice guys finish last” we say.

History shows that when we feel vulnerable, we don’t want the nice guys. We will choose the Alexander the Great’s, the Julius Caesar’s, the Constantine’s, not the Gandis, not the Mother Teresa’s, not the Desmond Tutu’s. And where does that get us?

How often are the powerful good?

Bonhoeffer and the “Weakness of God”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer reminds us of this. Bonhoeffer was a pastor who lived during Nazi Germany. He founded a school that educated pastors against what the Nazis were trying to indoctrinate people with. The Nazis, as I am sure you all know, taught that Germany was God’s nation, the church, and the state were very much not separate, and so its leader must be God’s chosen, and Germany wanted to be strong and indeed was willing to be cruel to reclaim the prosperity it thought it deserved. Bonhoeffer saw this for what it was and denounced it as idolatry, even when most Christians in Germany didn’t listen. (Feel free to draw your own parallels to today’s political situation).

Bonhoeffer was censored by the police, and so, at one point he fled Germany for the US, only to reconsider and return. He believed that he could not rightfully lead the German people after the war if he ran from the problems they were facing.

So he returned, and in an effort to undermine the Nazis, he started using his contacts for the resistance. He began passing information around, some of which pertained to a possible assassination attempt on Hitler, which he was caught with and imprisoned and awaited execution. This part of his story is kind of complicated and debated as Bonhoeffer was, by conviction, a pacifist, but it seems that he was willing to help the resistance, and what that meant for his convictions is not clear.

Whatever the case, as Bonhoeffer awaited execution in prison, he kept a journal and wrote profound papers reflecting on the meaning of Christ in this messy, modern world he saw, this “world come of age” he called it.

Bonhoeffer realized how the power of God came to be used to justify the power of the state, the power of dictators, the privilege of the people against other people, and how the church can get corrupted by all this all too easily. If God is primarily about power—if that is the primary way we think about deity—then there is a dangerous possibility that you can easily slide from worshiping the God who is powerful to simply worshiping power itself. When you do that, you will be more than willing to oppress or even kill anyone who threatens your power.

How often are the powerful good? Not very often.

And so, in his Letters and Papers from Prison, Bonhoeffer wrote these famous words:

“[God] is weak and powerless in the world, and that is the way, the only way, in which he can be with us and help us… Man’s religiosity makes him look in his distress to the power of God in the world… The Bible, however, directs him to the powerlessness and suffering of God; only a suffering God can help.”

The God who can save humanity must be a weak and suffering God, a God humble and lowly.

Why? It is only this that breaks our fatal addiction to power and privilege, our proclivity to solve our problems with violence and greed.

After all, if God is only a God of power like Zeus or Odin or Baal, who will one day obliterate all his enemies, why shouldn’t we do the same?

If God is the lofty God that does not tolerate any grievances against him, why shouldn’t we do the same?

If God is just a dictator in the sky, even if he is the most powerful one, this will never stop us from worshiping earthly dictators and secretly dreaming of how it would be nice to have that kind of power ourselves.

We can never see God’s kingdom by stockpiling power; we will never see the kingdom by eliminating our enemies. It doesn’t work like that. It never has.

This is a part of the lesson Jesus is trying to show us when he rides into Jerusalem on that first Palm Sunday. See your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, but lowly—humble—and riding on a donkey.

Jesus, the King who Refuses Status

Jesus, throughout the Gospels avoids and rejects the marks of status and position. It is not the way. Even though he, of all people, deserves it. He is a descendant of David, after all. He is someone claiming the status of messiah, the rightful king of Israel. He is the one shown by the Spirit to be the bearer of God’s kingdom, God’s presence. The dove descended on him in baptism, claiming, “This is my beloved Son.” He is favored by God.

What does Jesus do with this status? When you look at the Gospels, you see Jesus very intentionally refusing to take up his status or seek recognition. He does things that almost bewilder us like when he heals a person, he just tells them to show themselves to a priest and go on their way as if he does not want any money or fame from it all.

Or when Peter confesses that Jesus is the Messiah, Jesus tells him not to tell anyone. That’s a head scratcher: Hold on, there is a new king in town, and you don’t want us to spread the word? It’s like he is a completely different kind of king.

Jesus could have marched himself into a palace and said, “This is mine now.” He could have demanded servants bring him the finest clothes, the best foods, the purest wine, the latest version of the Iphone. He could have raised an army and punished anyone who questioned him. He could have made the masses bow down to him and grovel.

But if he did, would he be offering us anything different from what we see in the world today?

Jesus: born to a poor peasant girl, suspiciously out of wedlock.

Jesus: born in an alleyway stable, found lying in an animal’s feeding trough for a crib, wrapped in rags.

Jesus: the homeless rabbi, who has to live off of the donations of a few women.

Jesus: the miracle worker, who does not want any credit for what he does.

Jesus: who, after giving the most clear instructions on who he is at the Last Supper, took a towel and began to wash his disciples’ feet like a household servant.

Jesus: who when a band of thugs came to arrest him on false charges, refused the path of insurrection and violence and, in fact, even healed one of the men sent against him.

Jesus is showing us a different way.

Jesus: executed on a Roman cross—the most shameful way to die in that world—betrayed by his own disciples, denounced by his own religion’s authorities, abandoned by the people that just days earlier declaimed them his king, did not curse anyone but prayed, “Father forgive them. They know not what they do.”

Let’s just put it simply: If Jesus is the kind of person who cared about being treated with the importance he deserved and if Jesus cared at all to use his power to make sure the people who wronged him got what they deserved, our prospects for salvation would be zero. But that is not who Jesus is.

As Jesus said to his disciples, “The Son of man came not to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45)

Or Paul says in his letter to the Philippians, chapter 2. Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very natureof a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross!

Not a “Clark Kent Christology”

Now, often when I have heard this, I know what I have thought, and I think a lot of Christians have a tendency to read this with what I like to call the “Clark Kent Christology.” Because, again, we want Superman. We want the power, not the humility. We prefer to believe that Jesus really is Superman incognito. He came for a short time disguised as Clark Kent. But you better watch out, because any moment he is going to go into a phone booth and come out in all his glory and start beating people up.

Yes, Jesus is coming in resurrected glory, but it would be a fatal error to see this as different from what he has been showing us his whole life till that point.

And if we make that mistake, we are back to where we started again: A God whose power works all too similar to the powers of this world.

But the Gospels are not trying to say this: Jesus did not become less God by becoming human or any less God by becoming a servant or any less God by dying on the cross for us. Quite the opposite.

The Apostles use all kinds of language to express this mysterious truth: The Gospel of John says Jesus is the logos of God, the word made flesh. Paul says in Colossians that Jesus is the visible image of the invisible God; Jesus, the one in whom the fullness of deity dwells bodily. The Letter to the Hebrews says that Jesus is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being.

These are all trying to get us to see that when we look at Jesus, the God who gives up the powers and privileges we think God rightfully has, we are actually looking at the very essence of God: a God who forgives the worst wrongs done to him, a God willing to suffer with us in our darkest moments, a God willing to be in those god-forsaken places like an execution cross.

This God does not put his status above others. This is a God of humility, and this is how we know God is with us.

The Gospel of John even goes so far as to call the cross of Jesus his “glorification” as King, as if to say, if you miss seeing God here in Jesus, on this cross, suffering and dying in this wretched place. If this is not the apex moment for how you think about God, you have missed the point, and you are very likely going to miss seeing God with you in your lowest point, too, sadly. The two are connected.

That is the point of Palm Sunday. The humility of God is the true power and glory of God. Neil Copeland writes about this in a poem:

Mary sang to the unborn Christ,“The Lord on high be praised,

Who has brought down the mighty from their thrones,

and the humble to honour raised!”

And if she had heard the laughter of God,

Still she would not have seen the joke,

When her son rode into Jerusalem,

Riding his borrowed moke,

As all through the shouting jostling crowd,

And over their cloaks he trod—

The highest of all on a poor man’s beast,

And a donkey the throne of God!

Copeland’s poem says there is almost an ironic humor to the whole thing—the “laughter of God,” “the joke”—God raises up the lowly by showing us the true power of humility.

It is the humility of God that is our hope. It is the weakness of God that saves us. It is a notion so counter-intuitive to what we want and know. It sounds almost blasphemous to think about the weakness of God, but that is the words the Apostle Paul himself used to get us to realize the truth we need to hear:

“Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength. Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him. It is because of him that you are in Christ Jesus, who has become for us wisdom from God—that is, our righteousness, holiness, and redemption.” (1 Cor. 1: 24-30)

The Humility of God is the Possibility of the Church

Did you hear the connection there? The humility of God, the weakness of God—this is also the possibility of the church, the possibility of real change, for this is the true wisdom and power of God.

How often do we forget this? In the 1990’s, the Baptist Pastor Jeffery Brown came to a small church in a dilapidated part of Boston. Violence in Boston at the time was careening out of control. Gunshots could be heard through the night most nights. Brown tells the story of how he prayed that God would do something, feeling powerless, like he was too insignificant to be able to do something about what plagued his community.

When a young man was killed on the doorstep of the church, Brown realized that God was calling him to do something. Sometimes, when you pray for change, God calls you to be that change. So, what did he do? He decided he would start a group of pastors, and they started staying out at night, coming up to gang members and befriending them, hoping to see if this would make some difference. People said that doing this was a waste, unbecoming of a pastor to do. In fact it was not safe.

Yet, in time, the gang members started trusting these guys and the pastors started asking these boys, “Do you really want to live like this? What can be done to actually help make sure you boys are safe so that you don’t need guns, drugs, and violence?” They listened, and they were able to engage community services.

Through Brown’s efforts, gang violence went down nearly 80%. The result, you can listen to Jeffery Brown’s amazing Ted Talk on this. It came to be called the “Boston Miracle.” They call it that because, sociologically, that level of violence reduction is impossible.

The change did not come by some slick politician making promises. It did not come with some grand show of force to clean up the streets, to arrest and jail all those criminals that society deemed irredeemable. It came by ordinary people, these pastors, getting over their feelings of security and status to go out and dwell with struggling kids on the street. That is all it takes for miracles to happen.

If God can use the cross to defeat sin and death in all its weaknesses, God can use you. God can use us. God can choose people who feel they have no business claiming to be holy and respectable, let alone powerful and important, to do the things we sometimes only believe are reserved for those who are worthy.

The kingdom of God does not come through billionaires or celebrities. It does not come to the extraordinary and special. It is not reserved only for some elite class of super-spiritual folk.

The kingdom of God is possible in you and through you, in us and through us: the body of Christ.

If you can imagine the strange sight of a group of pastors hanging out with drug dealers, playing basketball with gang members at 2:00 in the morning, you are not far off from the feeling it might have been to see Jesus that first Palm Sunday.

And what will we see if we dare to imagine Jesus’ way in our lives, in our communities today?

See your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, but lowly—humble—and riding on a donkey.

Amen.