One with the Father: A Trinitarian Meditation for Father’s Day

Preached at Valley Gate Vineyard, June 16, 2024 (Father’s Day)

20 “I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. 22 The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. 24 Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory, which you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 “Righteous Father, the world does not know you, but I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made your name known to them, and I will make it known so that the love with which you have loved me may be in them and I in them.” (John 17:20-26, NRSV)

In this passage, Jesus prays for the church, and in this prayer, he speaks about his relationship with his Father, how they are mysteriously one: the Father in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the mystery of the Trinity that the Father is fully God, the Son is fully God, and also the Spirit is fully God, each showing that they are distinct persons and yet, they are one, one relationship in each other and through each other.

Now, I am a theology professor. I get to teach folk about this stuff, and sometimes, let’s just say, students are less than thrilled to dive into the tough stuff. Most grant that there is something about doctrine that is important. This thing called truth; we are all big fans, and so, the Trinity is worth a nod to being fundamental. Now, that can all sound well and good, but it is also quite mysterious and abstract, and who has time to understand all that stuff? Sure, the Trinity is important; sure, it’s fundamental but it is also kind of fuzzy.

That Father and the Son are one, the Son in the Father, the Father in the Son—what does it mean to be at one? What is the Trinity trying to teach us (especially today on Father’s Day)? Isn’t all this oneness talk just impractical abstract mysticism? Are we right to ask, as modern people, is all this really useful?

And while we are at it, isn’t talking about God as a father a bit sexist, a bit patriarchal? Again, we, as modern people, are we right to ask: why should I look to this ancient book called the Bible, a book that has caused wars, sanctioned slavery, suppressed science, and supported sexism? What could we learn from looking at this old language of God as a Father? What can it possibly say to our experience of our fathers and, for some of us, our experiences as fathers and how this relates to God?

One time, I was camping on the shore of Lake Erie with a group of friends for our friend’s bachelor party. Of the group of guys, most were from our Bible college, all except one, who Craig knew from his work. Upon realizing this, my Bible college mates inquired about whether he was a Christian or not. The guy merely said that he “just wasn’t all that religious.” Another guy in the group saw this as an evangelistic opportunity. The conversation frustrated the non-Christian guy. He left and went over to where I was sitting. He was visibly annoyed, and I cracked a few jokes to lighten the mood. We chatted there under the stars, glistening off the gentle waves of the lake. I was smoking a nice Cuban cigar. Eventually, curiosity got the better of me: “So, I am curious; what do you believe about God?”

“Well, I don’t know. My father brought us to church, and he was an alcoholic jerk. The stuff he did to my mother and me…” It went on something like this, and I had to interject.

“I asked you about God, and all you have said to me this whole time was about your Father.” The guy paused. He had not realized what he was doing.

I don’t recall the rest of the conversation, but it illustrated to me just how important it is to think about how we talk about God. How we talk about God is always bound up with our relationships with other people. You can’t do one without the other.

I asked about God, and he immediately associated that question with his father. Why did he do that? Why did he connect them subconsciously?

This association between God and our fathers is something perennial in the history of religion and it is deep in the Western cultural psyche.

Almost everywhere that people started thinking about God, they started associating with God the qualities of their parents, particularly their fathers, and for obvious reasons. Our parents are the source of our bodily existence, the ones who care for us when we are the most vulnerable, and so, their example forms some of our earliest feelings of safety, security, and provision. They form our earliest thoughts on what is ultimate in life, what is right and wrong, desirable or undesirable.

And so you have these analogies that appear both in the Bible and other religions: God is like a mother because God creates us like a mother birthing her child or sustains us like how a mother nurses her child. God is like a father in that since usually men are the physically taller and stronger members of the household, God is powerful and protective like a father. Because of this perception of power, the leader god in most pantheons in most ancient religions is usually a father-god, not a mother-goddess.

Now, if that is all that is, surely with changing times where both parents work, and gender stereotypes are frowned upon, then yes, referring to God as a Father is out of date. After all, women can be strong, and men can be nurturing, and so on and so forth. But is that really what is going on in the Bible? (I would point out to you that there are actually a number of references to God as female and motherly in the Bible as well if you look for them). But the bigger question is this: Is God really just a projection of what human relationships are like? Or is God ultimately beyond all that? If we think of God as a father, how does God show us what he means by that?

And on the other hand are we so different from ancient people? Our culture still experiences something that ancient times experienced: conditional love, absent love, broken love.

According to Statistica Canada, in 2020, there were 1,700 single dads under the age of 24. Also, in 2020, however, there were nearly 42 000 single moms under the age of 24. There were 21,000 single dads between the ages of 25 and 34 in Canada in 2020 where there were 215 000 single moms. Now, there might be lots of reasons and qualifications for these statistics (there are lots of single-parent households that are healthy and happy, don’t take this the wrong way), but it is safe to say that we still, culturally, are much more likely to be missing the love our of fathers on a daily basis than the love of our mothers. And, of course, that says nothing about the many double-parent families where the children have strained relationships with the parents they know.

We still face the same things as the ancient world, just in different ways. In ancient Greece, in cities like Sparta, if a child was not acceptable to the father, it was quite common, even expected, for the father to expose and kill that child. The father’s acceptance was conditional on whether the child was good enough and strong enough. For folks in this culture, they thought it was necessary: men need to be strong to fight wars. Weakness could not be tolerated.

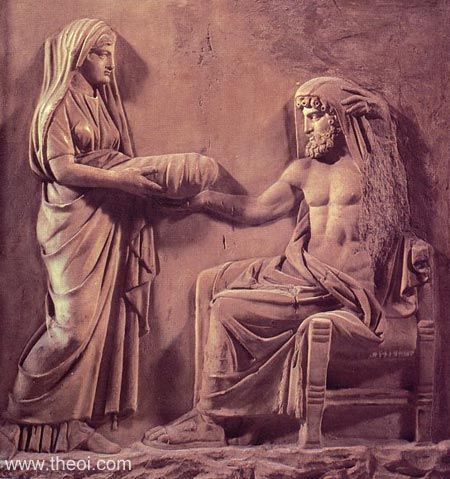

And this struggle to demonstrate one’s strength appears in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, there are two primordial Gods: the mother earth goddess, Gaia, and the father-sky God, Uranus.

They give birth to powerful monster gods called the Titans, the most powerful of which is Cronos, who resents his father’s rule and kills his father, becoming king-god. However, Cronos then becomes fearful that his children will usurp him, so he gobbles them up one by one after each one is born (Greek mythology is strange that way, I know).

However, one of his children, Zeus, is hidden from him and raised in secret, and it is Zeus who grows up to slay his malevolent father, assuming power to reign justly, at least for the most part. Zeus, however, in turn, fathers many illegitimate demi-god children, like Hercules and about 16 others in Greek lore, who grow up not knowing who their father is, often trying to do heroic quests to win Zeus’ approval.

Zeus slays his father, but he can never become a true father, it seems, in turn.

Deep in the religious consciousness of Greek religion is this conflict, this worry: If power is what makes a man, what makes a father, what makes a god, how can any son measure up? (But on the other hand, how can a father ever truly be a father either, if all he is obsessed about is power?) Or if the son is stronger, what is stopping them from replacing or usurping their weaker father, taking what their father has by force? And if that is the case, is Zeus all that different from Cronos? If power is what it means to be man, a father, or a god, then the more Father is like Son and Son like the Father, the more estranged they will be, the more they will fight, whether it is humanity to God or humans to one another. They cannot be at one.

I had this illustrated to me in one of the most profound movies on the effect of absent fathers I have ever seen. It is in the movie The Place Beyond the Pines. Ryan Gosling plays Luke, a motorbike stunt performer for a circus. He is a lone wolf, rough around the edges, a guy from the wrong side of the tracks. However, he learns that his ex-girlfriend had a baby, and it is his. He tells her that he loves her and wants to be for their child what his father never was: a provider that will come through for them. However, he admits that working for a circus does not pay well. He can’t afford the things he believes a father should be able to afford for his child. His girlfriend, however, just assures him that being there is enough. But Luke is afraid that he will be inadequate, just like his father was to him. So, his buddy tells him that if he wants to be a real man and provide for his family, he has to use whatever skills he’s got to do it. For him, it is his exceptional skills on a motorbike that could be used for something else: robbing banks and alluding to cops. Luke, in desperation, agrees. He robs the bank and speeds away from the cops on his bike almost effortlessly, and he is able to take that money and buy a crib and clothes and baby food and even take his family out on a dinner date. However, he realizes he will need more, so, he tries a double robbery, but it goes south, and in the mess of trying to allude to the cops, one cop, Avery, played by Bradley Cooper, shoots him and kills him, even though Luke is unarmed.

At this point, the movie shifts the main character from Luke to Avery. Avery, we learn, is a workaholic cop, being a cop is everything to him, despite him having a young family. For Avery, being a man means being a good cop. However, Avery is stricken with guilt over killing an unarmed man, something a good cop would never do. but Avery’s fellow cops cover up his fatal error, but this does not make him feel better as he learns just how corrupt some of his fellow cops are.

Moreover, he learns that Luke had a son about his son’s age and that the reason why Luke turned to crime was to provide for him so that his own son would be proud of him, the same reason Avery joined the police force, to make his dad proud of him. Because of the guilt, Avery can no longer stand to be around his own son, unable to be a father to his own son, knowing how he took some other boy’s father, punishing himself by denying himself a relationship with his own son.

The movie concludes years later. Avery is running for office, a workaholic relentlessly working for government reform, but doing this deep down to make hopeless amends for killing Luke. However, along the way, his son and Luke’s son, both teenagers now, both wayward and troubled from not having a father figure, meet and realize that while initially hate each other, Luke’s son sees the possibility of enacting revenge—they realize that they are the same: one had their father taken by the other, but the other never had his father to begin with, despite them living in the same house. And yet, ironically, sadly, the two of them show signs of becoming just like their fathers, one a reckless wonderer, the other a perfectionist.

The more Luke resented his father, the more he became like him, and this conflict, this estrangement continued from his father to him, but now from him to his son, who, just as ironically, ends up just like him. If our value as men, sons, and fathers is equated with our performance, we will not be at one with each other.

Think about that yourself. For many of us, we had good relationships with our fathers, but perhaps you did not. How has that affected you? Will we choose to see how our fathers are in us, whether this is good or bad?

Well, again, we like to think that we are better than all this ancient barbarism and mythology, but we are not all that different. The same human nature is within us, and there is the same realization: with so many of our relationships, especially ones as important as the ones between parent and child, we are not at one.

And there is an irony to all this with religion: We as a secular society believe that now that we are smarter, more educated, more technologically advanced, more politically organized…more powerful, we don’t need God. Isn’t secular society just one more attempt to kill Cronos all to end up just like him.

“God is dead, and we have killed him,” said the philosopher Nietzsche, declaring that to live in the modern world was to live with a rejection of God as an idea that was useful and meaningful to life. To live in a secular world is to live in a world that has pushed out God, religion, and even objective morality, all in the name of our own will to power. But even Nietzsche worried whether humans were indeed able to live without God.

We live, as George Steiner once said, with a “nostalgia for the absolute.” We live with an awareness that something is missing, something is absent, and for many of us, we live our lives trying to fill that void with something else, whether it is work, achievements, money, sex, or just mindless consumption and entertainment, whether it the socially expectable kind like Netflix or video games or ones less so like drugs.

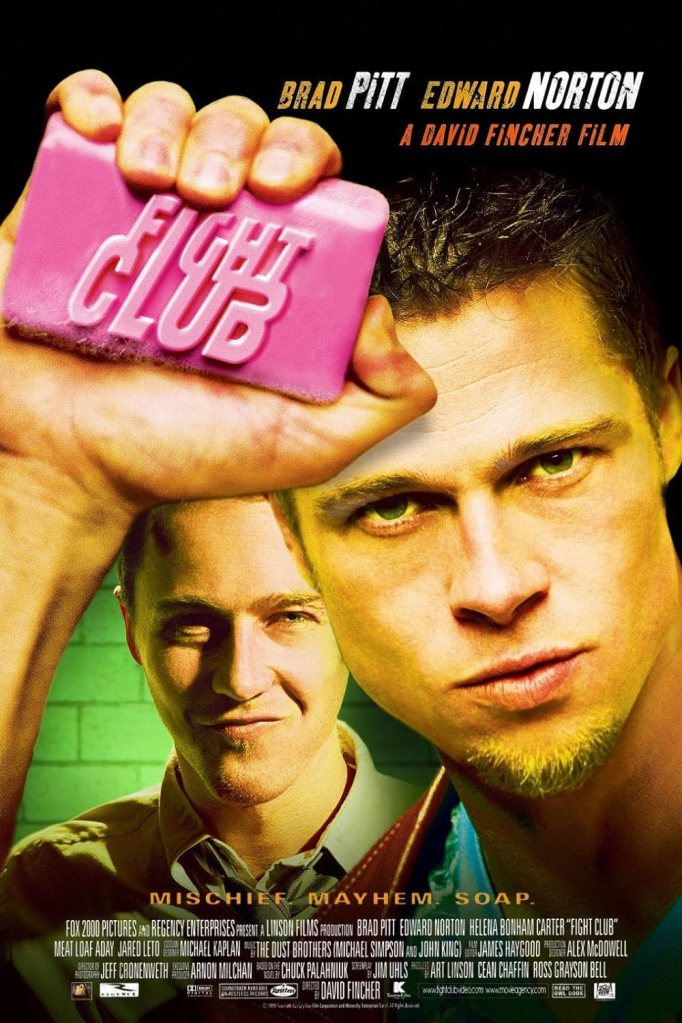

I had this connection between God the Father and our fathers in a secular world illustrated to me in one of my favorite novels of my young adult: Fight Club.

Fight Club, for those who don’t know this cult classic, is a story about a man who works a meaningless job for a greedy company. His life has no purpose, so he finds himself unable to sleep, passing the time by ordering useless products from shopping channels. However, he meets a man named Tyler Durden, who convinces him to punch him one night after a few beers in order to make him feel better. The man does, and the two start sparing, punching each other. It feels therapeutic for them, so they start up a fight club in the basement of that bar.

Tyler Durden and the main character talk about their past and about God, and both realize that they had fathers walk out on them, and they feel like this is a reflection of what God is like, too. Other men join this fight club, fighting others as a way of expressing their rage over their meaningless lives. Tyler names their struggle in one monologue he makes:

“Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering…an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables—slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy [stuff…he says something else here] we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man: No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war; our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day, we’d all be millionaires, movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Other chapters of these fight clubs start opening across the nation, and Tyler Durden starts manipulating them into cult-like cell groups, sending the men out on missions to vandalize corporations, with the grand scheme of blowing up the main buildings of VISA and other credit cards and banks, effectively resetting civilization. Tyler believes that he is some kind of messiah figure for himself. The narrator explains Tyler’s motives this way:

“How Tyler saw it was that getting God’s attention for being bad was better than getting no attention at all. Maybe God’s hate is better than His indifference. If you could be either God’s worst enemy or nothing, which would you choose? We are God’s middle children, according to Tyler Durden, with no special place in history and no special attention. Unless we get God’s attention, we have no hope of damnation or redemption. Which is worse, hell or nothing? Maybe if we’re caught and punished, we can be saved.”

Do you know people that say they don’t care about God but are living like they are desperately trying to get God’s attention?

And in a secular world, where we live either ignoring God or feeling God’s absence, as well as living in a world where masculinity, our worth as fathers, is so often defined by power as well as the money we make and the stuff we own or achieve, relationships like the ones between child and parent will be marked with conditions and expectations, caught in this vortex of conflict, competition, and estrangement.

If God is not love, no matter whether we run for God, ignore him, disbelieve him, or hate him—if God is not love, we will end up just like him: unloving ourselves.

I say all this to say that there is a longing deep in the heart of humanity, a longing for meaning and purpose, for acceptance and love, and this longing is symbolized in God the Father so often because of the role our fathers play, whether for good or ill, and it is a longing for oneness.

We have to ask a question fundamental to our future as humans: who is this God that we so often look to as a father? Does God care more about ruling unquestioned than loving his children for who they are? Is God the kind of God that will reject us if we don’t measure up? Will God ignore us if we ignore him? Is love conditional? Is oneness possible? Oneness between God and humanity and humanity with each other?

Well, the story of Scripture tells a different story of God as Father. To confess Christ is to attest to how we have found ourselves in a story where the Creator of all that is chooses to create people in God’s image and likeness. Image and likeness was a way of talking about one’s children. A child is in the parent’s image and likeness and so, God makes all people to be his children, making them with dignity, designing them to reflect his character of love as the way they can most authentically be themselves.

This God reveals himself in history, calling Abraham out of his father’s household, out of idolatry, and into redemption, promising to bless and protect him.

This God led the Israelites out of Egypt, a people oppressed and enslaved under idolatrous tyranny, and God told them that out of all the human family, Israel is to be his firstborn, a nation that has a unique purpose in reflecting God to the nations around it.

This God says God is One, the I am who I am, the living God, and this One God longs to be one with us.

This God says that he is like a father. However, even more than that, God is the perfect father, and God, as this perfect father, beckons us home when we have rebelled against him.

And so when we look at the narrative of the Bible, we see this One God revealing who God is in this pursuit of being at one with us in a way that mysteriously takes on—for lack of a better word—different dimensions to God’s self: the God who is beyond all things, infinite, transcendent, and almighty, but is also the root of all existence, the breath of life, the presence of beauty, one in whom we live and move and have our being, the movements of love, known as Spirit.

As the narrative shows, these dimensions relate to one another. God sends his messiah, the king, but a king that is more than another human king; he is God’s only begotten Son, one with the Father. There is no conflict between Jesus and God because they are fully one with each other to the point that when you look at Jesus, you see the visible image of the invisible God. God is not a distant God. He is with us.

The Father sends the Son, Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly enfleshes the presence of the God Israel worshiped but also fulfills the longing for righteousness, this reconciling oneness with all things Israel was called to, and Jesus does so through sending the Spirit.

This story clashes with human sin, however, and it comes to a particular intensity when people reject Jesus’ invitation to step into the oneness of God. John says at the beginning of his Gospel: “The world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him.” We know how this story goes.

Jesus died on the cross, executed by an instrument of imperial oppression orchestrated by the corrupt religious institution seeking to preserve its own power, but also betrayed by the ones Jesus was closest with, his own disciples and his friends. The cross discloses the tragic depth of our tendencies to refuse to be at one with God and others, even when literally God is staring at us face to face.

But it is in these dark moments that God showed us who God is.

For Jesus to die one with sinners, yet one with the Father, reveals God’s loving solidarity with the human form—our plight, no matter how lost or sinful. God chooses to see God’s self in us and with us, never without us. God chooses to bind himself to our fate to say, “I am not letting you go.”

To be a part of the family of God is to trust in Jesus Christ; it is to remember that in these moments of condemnation, we have been encountered by the presence of the Spirit, a love that invites us to see that we are loved with the same perfect love the Father has for his own only begotten Son. The same love that God has for God in the Trinity, God has for sinners, for you, and for me. God is not going to give up on us.

Paul says it this way, “If we are faithless, God remains faithful.” Why? “Because he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim. 2:13).

That is the truth of the Trinity. Trust this. God has made a way for him and us to be one as he is one.

And if God is like this, this suggests ways our relationships can be healed and improved.

Can this propel us to love our fathers more, not merely for all that they have done for us (or have not done for us), but to love them for who they are, to love them as God loves them, to see ourselves in them and reckon with that, with thankfulness, with forgiveness, with gratitude and grace?

Can this change how we think about our own children? If God sees himself in us, can we empathize more with them, seeing ourselves in them, rather than just making sure they shape up to what we expect? To be there for them, love them for who they are, and the journey God has them on.

And God says, “May they be one as we are one.”

Let’s pray…

Thank you Spencer for sharing this with me. I have previously never really thought about the Trinity along those lines. Thank you for opening up my eyes. Keep up the good work.

Love you guys.

Marrilynn ________________________________

LikeLike

Oops, I attached my note to the wrong email. It should be to ‘One with the Father. Just getting old I guess.

LikeLike

Oops, I did it again. It should be attached to ‘Longing to be One’. I haven’t yet read One with the Father’.

Lock me up, and throw away the key!!

Marrilynn Boersma marrilynnb@hotmail.com Sent: June 17, 2024 8:48 PM To: Spencer Boersma comment+l_e1ete8-mv-zijivu6cyk-@comment.wordpress.com Subject: Re: One with the Father

Thank you Spencer for sharing this with me. I have previously never really thought about the Trinity along those lines. Thank you for opening up my eyes. Keep up the good work.

Love you guys.

Marrilynn ________________________________

LikeLike