Tagged: Liberation

Making God’s Name Holy

Delivered at Billtown Baptist Church, Feb. 23, 2025.

So, we are going through the Lord’s Prayer. Pastor Angela has covered “Our Father in Heaven.” She’s been taking her time. She began with “Our,” then “Father,” then last week, we were away in Halifax for family day, but she tackled “in Heaven.” I got a whopping four words to cover this morning. At this rate, we may be done this series sometime next year. I am only teasing.

I tease but I feel like doing this reminded me to slow down. I am the kind of person who reads and reads and wants to get things done and move on to the next thing. That is how we live our lives. Our lives can so often be the rat race of getting things done on to the next thing to get done.

I remember one time at Laurentian University, where I used to teach; my day would also be so filled with things I needed to get done and events I had to plan that I would make a to-do list in my head and motor through them. One of those, often, was getting books from the library, which was several buildings away from my office, so I would quickly walk there and try to get back as fast as I could. One day, I remember I was just feeling a bit tired so I got a cup of coffee in the Starbucks in the lobby just before going into the library. I remember pausing for a second to sip the coffee, and then I looked up and realized there was a massive art piece on the wall coming into the library. It was of several blue orchids painted in that impressionist style that was simply stunning, and I had this moment of realizing that I had passed by this art piece many times and just never bothered to notice because I was too busy.

We can do the same thing about God, and we can do the same thing with the Scriptures, too, if we don’t slow down.

And this is particularly important with words that often are so familiar to us like these ones. We can say them and not stop to think about them. I remember talking to a pastor one time, and he talked about how growing up, his dad would always pray the same prayer at dinner time (I am totally guilty of this—by 5:30, I’m tired and but hangry, originality or anything profound is just not coming out of my mouth as my kids bicker—often my prayers just end up sounding like parental auto-suggestion: “God help us all to be nice and be grateful for our food. Amen!”). Nevertheless, this guy’s dad would pray the same puzzling words every day: “God bless this food and antenna juice.” And for years, he said to me, he was always puzzled about why his dad prayed for the “antenna juice.” Finally, he could not hold it in any longer and he asked his dad one day, “What is going on with the antenna juice?” And did you figure out what it is? His dad, puzzled, said, “I pray ‘God bless this food for its intended use.’” Ohhhh! (The other moral of the story is that a little annunciation goes a long way.)

“Hallowed be your name”…?

Words we recite day in and day out can end up becoming routine. We can say them without thinking about what they mean, and I particularly feel that with this line in the Lord’s Prayer, “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed by your name” (as I learned it in King James English). I remember thinking as a kid, “Why is God’s name hollow?” that does not make a lot of sense. Of course, eventually, I figured out that it is actually “hallowed” or “to be made holy,” but that didn’t really clear things up either: Why is God’s name need to be made holy? Isn’t God already holy? How do you “hallow” something, especially when that something is God’s name?

There is something really important and nourishing about slowing down and thinking about the Scriptures little by little, word by word. That is what I am going to do this morning. Let’s re-ask those questions: What is God’s name? Why is God’s name being brought up here rather than just God? What does it mean to be holy? And why does this line of the prayer petition God to make God’s name holy?

So, first, what is God’s name? Some folks think “Father” is the name of God in this prayer, and that is not actually accurate. Father is a title of God with its own particular history that Jesus used to talk about how he is the Son of God, the Messiah.

What is God’s name then? We see what it is back in the book of Exodus. Moses comes to the burning bush, and God says he has heard the cries of his people. He says he is going to send Moses to liberate the people from slavery, and after that, Moses asks, “That’s great, but, by the way, what do I call you if anyone asks?” And God gives this strange answer, “I am who I am.”

Ancient names meant something. At some point when Meagan and I were dating, we would chat about whether we were to have kids and how many (the answer at the time was three, by the way). But we also talked about hypothetical names for our kids, and we could never agree on one. I remember one time at the church we attended in Cambridge, Ontario, this couple introduced themselves to us, and then they turned and said, “This is our boy, Rowan.” I remember thinking to myself, “I really like that name.” Then I turned to Meagan, who had a look on her face like she was thinking the exact same thing. Then I realized in my heart what we had to do: We could not be friends with these people because we needed to steal this name and claim we creatively thought of it ourselves as good millennials.

Admittedly, we have really only chosen names that have a nice sound to them. That is really subjective. There really wasn’t any deeper meaning to why we chose our kids’ names. Rowan means “from the Ashberry tree.” I still, to this day,don’tt know what an Ashberry tree looks like.

Well, the ancient people took the meaning of names a bit more seriously than Meagan, and I have, and God gives his name to Moses, and not “Bill” or “Dave” or anything you can just casually write on a name sticker with a sharpie during an ice breaker event. It is this mysterious, perplexing name: “I Am who I Am.” What does that mean?

That is kind of a strange name. It almost feels comical, like something out of an Abbot and Costello routine: Who is on first base? Who is. The man’s name is Who. That’s who.

Moses asks, “Who are you?” and God says, “I Am. I Just Am.” That is the name God chooses. Why? Well, in ancient culture, if you knew the true name of a god, you could control and invoke the power of that god as a magical incantation, or so the priests of Egypt thought. For God to reply, “I Am who I Am,” is saying who God is goes beyond this whole exercise of naming and controlling.

I am beyond your concept of what God is;

I am not one god amongst others.

I am beyond all beings;

I am the source of all being itself;

All other gods are nothing compared to me; I am the one who simply is.

God gives Moses this name, which writers in church history have sometimes called the “Nameless Name” (cf. Ps. Dionysius) as a way of reminding people that God cannot be thought of or controlled like other gods. God is simply the one who is.

Salvation in God’s Name

And yet, God also says to Moses, “I am with you.” This God whose name suggests God is the absolute purity of existence, something infinite and incomparable, this God is not far off, aloof and unconcerned with the world; this God chooses to come alongside this small, insignificant, enslaved nation, to walk with people in the midst of everyday life and their struggles. This God chooses to make promises of liberation. And what God does with Israel is a sign of what God is about for all humanity.

This God is the one who is.

This God is the real God.

This God has real power.

This God is truly just.

This God is compassionate and gracious.

This God is on the side of the forgotten and unworthy of the earth.

This God can be trusted.

So, beginning with Exodus, God sets out to, we might say, make a name for himself, and Israel is called to testify of what God does to the surrounding nations. Their history is to be like a living resume to the rest of humanity, showing that God is trustworthy and up for the task of redemption. God sets out to act in such a way that when people hear about the God of Israel, this God who is the I Am, the one who is (or in Hebrew, Yahweh), this God is different.

That is what holiness means, by the way. The Hebrew word kadosh means to be set apart. Something that is holy is different. This God is a holy God. God is different from the rest.

Throughout the Old Testament, you have God’s people invoking God’s name to say, “Come and save us. We know that you are the God who will.” Psalm 53 does this.

1 Save me, O God, by your name,

and vindicate me by your might…3 For the insolent have risen against me,

the ruthless seek my life;

they do not set God before them.4 But surely, God is my helper;

the Lord is the upholder of my life.

5 He will repay my enemies for their evil.

So, the people call on the name of God in prayer and worship by name.

In college, I had a friend who was a part of AA, alcoholics anonymous. He joined AA to clean up his life, and at the same time he found faith in Jesus and eventually felt called to be a missionary, and that is what he was studying for. I remember one time he took me to one of those meetings where visitors were allowed, and it was a humbling time for me to hear his testimony and others.

One part of all the testimonies mentioned one of the steps in the program, namely, trusting in a higher power. I remember talking about that with him one time. He said, you know, in AA, we are told to trust in a higher power, and for most, this could be anything: it could be Allah, Buddha, or some other deity from the great religions; it could be an angel, or the oneness of the universe, or the force from Star Wars for that matter—it really could be anything as long as you believe in something more than yourself since one of the qualities of the steps is realizing one’s enslavement to addiction.

Well, he said, that is all fine and good, but he said, I don’t know how you can believe in those other things and have any assurance you are going to be okay through all this. Of course, he did not mean it like Christians are better or that if you are a Christian in AA, you are obviously never going to struggle or fail at your addiction or any of that. What he meant is that lots of people believe in God or believe in a higher power, and that often helps make people better people. But the question becomes, what is God like, and how do you know this? If there is a higher power, that’s great, but is this higher power merciful? That is where the God of the Bible made a difference for him.

For him, it simply meant his higher power, the one he looked to for strength to succeed in sobriety and forgiveness when he failed, had a name. His higher power, whom he trusted, has a track record of being there for sinners. In fact, his higher power loves sinners so much that he died for them as one of them and rose from the grave to give them hope.

The name of his higher power that he trusted was Jesus, whose name means “God saves.” Jesus is the ultimate display of this “I Am” God capable of being with us.

This does not mean that we pray in “Jesus’ name” like it is a magic formula to make God do things or the secret ingredient in a recipe. Surely, God hears the cries of anyone, anywhere, regardless of how they pray. But we pray, invoking the name of God, the identity of Jesus, God’s Son, to remind ourselves and others that it is this particular God who answers prayer, who has shown himself to be faithful.

God’s Name is Being Profaned

Well, that still does not answer why Jesus tells us to pray, “Make your name holy.” In fact, that really makes things more confusing: Isn’t it already holy, isn’t that why we are praying to it?

Well, to answer that, we need to remember that things did not always go rosy for Israel, and things are not the way they should be in the world. Israel disobeys; they are unfaithful to God; they commit idolatry; they neglect the poor and engage in dirty politics with the empires of the world, and so, they get conquered and carried off into exile.

The people disobey God and feel the consequences, but God does not stop being their God. God has made promises of faithfulness and restoration that God has said he will keep despite their unfaithfulness. And so you have these prayers then in the later parts of the Old Testament, longing for God to come.

Ezekiel 39 gives a vision that one day, God will come, and he will make his name holy. Let me read the ten verses:

And you, mortal, prophesy against Gog, and say: Thus says the Lord God: I am against you, O Gog, chief prince of Meshech and Tubal! 2 I will turn you round and drive you forwards, and bring you up from the remotest parts of the north, and lead you against the mountains of Israel. 3 I will strike your bow from your left hand, and will make your arrows drop out of your right hand. 4 You shall fall on the mountains of Israel, you and all your troops and the peoples that are with you; I will give you to birds of prey of every kind and to the wild animals to be devoured. 5 You shall fall in the open field; for I have spoken, says the Lord God. 6 I will send fire on Magog and on those who live securely in the coastlands; and they shall know that I am the Lord. 7 My holy name I will make known among my people Israel; and I will not let my holy name be profaned anymore; and the nations shall know that I am the Lord, the Holy One in Israel. 8 It has come! It has happened, says the Lord God. This is the day of which I have spoken. 9 Then those who live in the towns of Israel will go out and make fires of the weapons and burn them—bucklers and shields, bows and arrows, hand-pikes and spears—and they will make fires of them for seven years. 10 They will not need to take wood out of the field or cut down any trees in the forests, for they will make their fires of the weapons; they will despoil those who despoiled them, and plunder those who plundered them, says the Lord God.

Gog and Magog are nicknames of the areas where the brutal Babylonians and Assyrians came from. Meschech and Tubal are in the northern mountain region of modern-day Iraq and Turkey. The Bible geeks in the room might know the phrase “Gog and Magog” from the book of Revelation, which re-uses the phrase as an archetype for any brutal military power, which, for the writer of Revelation, was the empire of Rome.

Ezekiel’s vision, which if you found it bizarre and jarring that is exactly what apocalyptic visions do to get us to think differently, is that these arrogant and violent nations oppressing people will come to an end, as all empires will, whether that is Assyria, Babylon, or Rome, or whether that is Russia, China, or the British empire, or the America empire. Their armies will be destroyed, but not only that, their weapons will be gathered up and burned for firewood, so much so that the people of God will be warmed by its heat for years to come, and they will live in safety, no longer needing weapons of war anymore.

Most importantly, (did you hear the line?), it says, “My holy name I will make known among my people; and I will not let my holy name be profaned anymore.”

God’s name was in a state of being profaned: insulted, tarnished, desecrated. Why? Because oppression is rampant on the earth and the innocent suffer.

God looks at the state of the world, the state of his people, the cries of the poor, the innocent, and the oppressed. God sees the rampant war. God sees hard-heartedness in God’s people, and God sees his name profaned.

Boy, I am sure glad we solved all those problems in the Old Testament, and that stuff never happens today!

Notice God’s response: God doesn’t just turn to us and say, “Well, I gave you a choice, and you really messed that up, so too bad, not my problem.” Although we certainly have made choices that have messed things up.

God doesn’t just turn to us and say, “See, you might think all this evil is bad, but I am actually all-powerful; I am in control; I can do whatever I want, even if that means causing or allowing terrible things to happen. So be it. So, how dare you question me?!” He doesn’t do that either, even though that is what many of us were taught growing up.

I remember talking to an atheist one time, and I asked him why he believed what he believed (there are, of course, many reasons for why someone is an atheist). The person said how he looks at the world and the evil in it, and he sees this as a contradiction to the existence of a good God.

I had to say, “I agree. But that is why I believe in God. Evil does not belong here.” Thankfully, I think God agrees too: God sees the evil of the earth, and God sees this as a contradiction to who he is. God takes the evil and tragedy of this world personally.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, in his book, The Prophets, writes about this:

“Why does religion, the essence of which is worship of God, put such stress on justice for humanity?… Perhaps the answer lies here: righteousness is not just a value; it is God’s part of human life, God’s stake in human history. Perhaps it is because the suffering of man is a blot upon God’s conscience; because it is in relations between man and man that God is at stake. Or is it simply because the infamy of a wicked act is infinitely greater than we are able to imagine? People act as they please, doing what is vile, abusing the weak, not realizing that they are fighting God, affronting the divine, or that the oppression of man is a humiliation of God.”

God looks at this world, broken and corrupted, this world he created, this world that belongs to him, this world he loves, and his people in his image, all humanity as God’s children, whether we have acknowledged him or not, us who are hurt and hurting others, and he makes promises to us: I am going to do something about his. It is an affront to who I am.

Do We Dare Pray this Prayer?

And so, Jesus, the one who is God Immanuel, gives a prayer to his disciples.

Pray this way: Our Father in heaven—Father of all creation, all humanity, a father to the oppressed and forgotten, the unworthy and unforgiven—our Father.

May your name be holy—God may you do something about how the state of this world is an insult to your justice and goodness, your reputation of the true and perfect God.

Look what it says after this: May your kingdom come and you will be done, on earth as it is in heaven—May your perfect goodness come to reside, be made manifest, break-in, shine through, restore and reorder every square inch of reality back to the way things ought to be, the way you desire them to be. So much so that when we look at heaven and we look at the earth, we won’t be able to tell the difference.

This is what this prayer is telling us to pray. There will be a day when what God desires for things and the way things are will be one and the same. One day, God’s name will be fully, unreservedly holy without exception or remainder.

This leads us to admit a kind of sad irony to how we pray the Lord’s Prayer. We recite the Lord’s Prayer, and it is so commonplace for many of us—so much for me, that I have caught myself yawning. Have you (no judgment)?

And I will be honest: Part of me would have been much more content if I just carried on reciting this prayer in the same thoughtless, boring, safe way. Why? Because thoughtless faith easily becomes selfish faith. And thoughtless faith does not bother to notice. Deep down, it does not want to.

I can recite this prayer, as I so often have, and my big takeaway from the prayer, if I think about it at all, is that God is in heaven. This world is awful and hopeless, so God wants me to go to heaven. So, God forgives me of my sins and promises to provide for all my needs, which is really convenient because, you know, have you seen the price of gas and groceries lately?! And that’s it. Amen.

And so, for many of us Christians, we can sing worship, delighted with how we get to escape earth and go to heaven, missing our calling that we are invited to bring heaven to earth, to live in such a way on earth as it is in heaven. We are called to make God’s name holy.

If this is what this prayer is saying, I’ll be honest with you: far from yawning at this prayer, we should ask ourselves: do we dare say this prayer?

One of the Ten Commandments is “You shall not take God’s name in vain,” and that is not referring to the words that come out of our mouths when we hit our thumbs with a hammer. It is whether we who know of God, who confess God, take seriously what that means with the way we live our lives. Have we taken God’s name in vain by reciting this prayer and refusing to live it?

The fact is sometimes we pray for God to answer our prayers, and the answer he gives is us. Be the answer to this prayer. Brothers and Sisters, will we make God’s name holy?

Do we dare to live this prayer?

Let’s pray.

Systems of Slavery and Our True Exodus

Preached at Billtown Baptist Church, January 15, 2023.

The Israelites, a people descending from a man named Abraham, came to live in a land called Egypt due to God working mysteriously and powerfully in the life of Abraham’s great-grandson, Joseph. Joseph was sold into slavery by his jealous brothers, but what they meant for harm, God meant for good, it says, and through these tragic circumstances, God uses Joseph, raising him up to second in command in the nation, and saves Egypt from seven years of famine. In doing so, he is able to provide for his family, who come to live there. Hundreds of years go by, and a Pharaoh arises who knows nothing of what the Israelite hero, Joseph, did, and he decides to enslave the people of Israel, making them work, making mud bricks. He is so threatened by how numerous they are he orders the destruction of newly born boys. One boy, however, is hidden by his mother and sister in a basket, a basket in the water that Pharaoh’s own daughter finds and raises Moses as her own. When Moses grows up and learns of his true heritage, he murders, in his rage, an Egyptian taskmaster and flees in Exile to Midian.

There it seems, he consigns himself to a modest life. He makes peace with the injustices he cannot change. He gets married. He tends sheep. But one day, he sees a spectacle: a burning bush, the divine presence appearing to him. And this divine presence speaks and reveals the name of God, “The I am who I am.” This God, who made promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob long ago, has heard the cries of the oppressed. This living God commissions Moses¾against his choice at first¾to go and tell Pharaoh to let God’s people be God.

Moses goes and talks to Pharaoh. He tells him God is ordering him to release the Hebrew people. Pharaoh’s response? “Who is this God that I should listen to him?”

And so, Moses warns that ten plagues will come upon Egypt, each showing God’s sovereignty over the gods of Egypt, each stripping Pharaoh of his credibility and, with it, the Egyptian resolve.

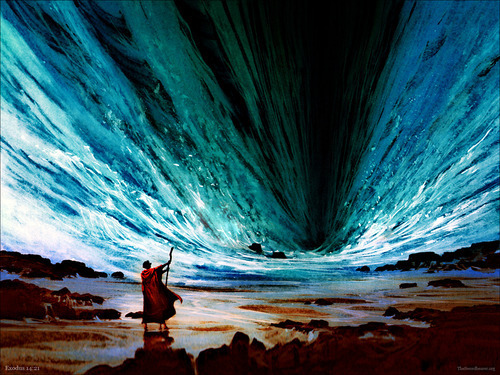

Finally, after the most formidable of plagues, the death of the firstborn, Pharaoh, relents. The people assemble to leave, and they march out into the wilderness. And this is where our scripture reading for today picks up. I am going to read the whole chapter, Chapter 14, and the first part of 15:

14 Then the Lord said to Moses, 2 “Tell the Israelites to turn back and camp in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-zephon; you shall camp opposite it, by the sea. 3 Pharaoh will say of the Israelites, ‘They are wandering aimlessly in the land; the wilderness has closed in on them.’ 4 I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and he will pursue them, so that I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, and the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord.” And they did so.

5 When the king of Egypt was told that the people had fled, the minds of Pharaoh and his officials were changed toward the people, and they said, “What have we done, letting Israel leave our service?” 6 So he had his chariot made ready and took his army with him; 7 he took six hundred elite chariots and all the other chariots of Egypt with officers over all of them. 8 The Lord hardened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and he pursued the Israelites, who were going out boldly. 9 The Egyptians pursued them, all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, his chariot drivers and his army; they overtook them camped by the sea, by Pi-hahiroth, in front of Baal-zephon.

10 As Pharaoh drew near, the Israelites looked back, and there were the Egyptians advancing on them. In great fear the Israelites cried out to the Lord. 11 They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us, bringing us out of Egypt? 12 Is this not the very thing we told you in Egypt, ‘Let us alone so that we can serve the Egyptians’? For it would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the wilderness.” 13 But Moses said to the people, “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today, for the Egyptians whom you see today you shall never see again. 14 The Lord will fight for you, and you have only to keep still.”

15 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Why do you cry out to me? Tell the Israelites to go forward. 16 But you lift up your staff and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it, that the Israelites may go into the sea on dry ground. 17 Then I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians so that they will go in after them, and so I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, his chariots, and his chariot drivers. 18 Then the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I have gained glory for myself over Pharaoh, his chariots, and his chariot drivers.”

19 The angel of God who was going before the Israelite army moved and went behind them, and the pillar of cloud moved from in front of them and took its place behind them. 20 It came between the army of Egypt and the army of Israel. And so the cloud was there with the darkness, and it lit up the night; one did not come near the other all night.

21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. The Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and turned the sea into dry land, and the waters were divided. 22 The Israelites went into the sea on dry ground, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left. 23 The Egyptians pursued and went into the sea after them, all of Pharaoh’s horses, chariots, and chariot drivers. 24 At the morning watch the Lord, in the pillar of fire and cloud, looked down on the Egyptian army and threw the Egyptian army into a panic. 25 He clogged their chariot wheels so that they turned with difficulty. The Egyptians said, “Let us flee from the Israelites, for the Lord is fighting for them against Egypt.”

26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, so that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots and chariot drivers.” 27 So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at dawn the sea returned to its normal depth. As the Egyptians fled before it, the Lord tossed the Egyptians into the sea. 28 The waters returned and covered the chariots and the chariot drivers, the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea; not one of them remained. 29 But the Israelites walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left.

30 Thus the Lord saved Israel that day from the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. 31 Israel saw the great work that the Lord did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the Lord and believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses.

15 Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song to the Lord

“I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously;

Exodus 14:1-15:3 NRSV

horse and rider he has thrown into the sea.

2 The Lord is my strength and my might,[a]

and he has become my salvation;

this is my God, and I will praise him;

my father’s God, and I will exalt him.

3 The Lord is a warrior;

the Lord is his name.

We can see in history moments of liberation, moments that seem exodus-like: where those things that we see as truly oppressive to people get dismantled or a higher moment of dignity for people is achieved.

In 1945, the allied forces finally overpowered the German forces. Germany surrendered with the tyrant Hitler dead and Berlin surrounded, ending perhaps the most brutal conflict in modern history. War was finally over. People did not need to be afraid anymore. The troops could come home. The nations Germany had taken over were free. News of the victory caused people to dance in the streets.

In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr crossed the bridge at Selma, peacefully confronting a small army of police who had brutalized the protesters days earlier. Walking prayerfully in a line, the protestors were resolute, and in a moment that came to be described as divine providence, the police relented. The protestors continued their march to Montgomery to advocate for voting rights for African Americans. The people on the march sang and praised God. What began as a few protestors swelled to tens of thousands, joining in the work of justice. Within several months they achieved what they were seeking.

In 1989, the Berlin wall was torn down: A wall set up by the Soviet Union to control their chuck of Germany after World War 2, separating families overnight for years. Finally, the wall came down. Many in North America watched their television screens as one segment smashed through, and the people on the other side stuck their hands through. Family members could see each other, touch each other, and, as the segments came down, were reunited in moments of pure joy.

There are many other events that we might describe as exodus-like: like the abolition of slavery, the day women got the right to vote, a country gaining independence, or, most recently for us, the day a vaccine was discovered. If you remember that day, the day you got tangible hope finally that the pandemic would end. These are moments of hope.

Just a few weeks ago, I read in the news that the hole in the O-Zone Layer is shrinking due to the global reduction of the chemicals that caused the hole. It will still take several more decades for the hole to be repaired fully, but with all the bad news on global warming, it was just so encouraging to hear about this little victory.

Each of these moments, no matter how small or even how secular, are pin-pricks of light showing through the shroud that enfolds us, glimmers of what God desires in human history: God wants to establish his kingdom on earth. God wants his will, as the Lord’s prayer says, to be done on earth as it is in heaven. God wants his goodness to heal every facet of this world, setting all that has gone wrong right again without remainder.

That is what this story in Exodus is pointing to. Martin Luther King correctly describes this story when he said this:

“The meaning of this story is not found in the drowning of Egyptian soldiers, for no one should rejoice at the death or defeat of a human being. Rather, this story symbolizes the death of evil and of inhuman oppression and of unjust exploitation” (King, Strength to Love, 78).

Martin Luther King went on to say, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

It is so easy to forget this when we look out at the world we live in. It is so easy to be disenchanted with the notion that God wills the hope of liberation for our world when we are inundated with messages of the world growing darker.

History does not feel like it is bending toward God’s justice. It feels more like one step forward and two steps back (or, in some cases, three or four or even a leap back).

I felt it in 2020 when we were scared in our homes from a pandemic that would come to claim more than 3.3 million people. The globalized world we live in all of a sudden felt so precarious.

At the same time, we in Nova Scotia witnessed a stand-off between indigenous fishermen and settler fishermen in St. Mary’s bay, a stand-off sparked by decades of neglect by the federal government to properly regulate, a clash fuelled by underlying resentment that explored into a racial conflict. And we say the pictures of violent mobs and fires. And I remember saying to myself: “We haven’t come as far as we think we have.” The injustices of the past linger in the present. As soon as people feel their livelihood threatened, good folk turn back to old hate.

We inhabit a world warped by a colonialist past and a present that still has so much exploitation and inequity in it. So many of our luxuries as Canadians, sold in our stores to us, which we thoughtlessly buy, are products made from exploited work or exploited resources from other countries.

When we think about it, we feel caught in this system of the world that simply is not the way things ought to be, and we don’t know what to do about that.

While these systems of greed and exploitation have afforded us westerners comforts that most of the rest of the world can only dream of having, we feel a strange sense that we are powerless in our own way. We feel enslaved to these economic and cultural forces (the “powers and principalities,” as Paul called them) that say to us: “You can’t do anything about this; this is just the way the world works. Get used to it. There is no changing it.”

When we know God’s will is goodness, truth, beauty, life and hope, then we look at the world and see that it has radical, systemic, and cosmic evil: that the world is not as it should be. We feel powerless against this. We feel trapped.

Why can’t we humans get our act together?

When we say there is something wrong with the world out there, scriptures push us to turn our attention from the evil out there to the evil in here, in our hearts. The inexcusable evil we do.

Otherwise, we do something sometimes even more terrible: we convince ourselves we are the righteous few, better than everyone else, the pure ones, God’s favourites among the damnable masses. When we delude ourselves into that kind of self-righteousness, we see history scared with those that felt they could take God’s wrath into their own hands rather than let God fight for us.

It is an old saying that when we point fingers, we have three fingers pointing right back at us.

Society has made advances and progress in many wonderful ways. Yet, it still has not changed the human heart: the same evil capacities remain in human beings that in light of all our education and knowledge, all our collective wisdom and arts and religion, and all our power and technology, we will still choose the path of annihilation, knowing full-well what it is.

When we know the vast waste and depravity of violence, we still go to war.

When we know that more is accomplished in unity, we still choose division, petty feuds and tribalism.

When we know the benefits of facing hard realities, we still choose to cling to our delusions and our comforts.

In this story of Israel and Egypt, if we are really honest, we must realize that we are more often Egypt than Israel. We are God’s people, and yet we live all too happy as people of Pharaoh.

We, as Christians, know that while our faith pushes us to love more and pursue truth more and justice more, we also are aware that our hearts can also contort our religion into instruments of apathy and self-righteousness.

We do this when we offer prayers that we don’t intend to act on.

We do this when we know the beauty of the Gospel and don’t share it.

We do this when we talk about salvation as a way of escaping all our problems rather than confronting them, a strictly spiritual reality that never offends, confronts, or transforms.

We do this every time we settle for an anemic, easy gospel that refuses to look at all the ways sin has its grip on us and, more tragically, all the ways we ignore the offer of eternal life, the fullness of life, the invitation into God’s kingdom because we are content with so much less.

We look out at the world, and we condemn its evil; we look at our country, and we realize we are living in a modern-day Egypt. And then we look at ourselves, and we have to realize we are no better.

We choose our chains.

C. S. Lewis once said it is our perennial tendency to be content playing in filth when God has shown us the path to the most beautiful beach right around the corner.

One ongoing detail of the Book of Exodus is just how much the people gripe and complain. Moses comes and says that God has sent him to rescue them from oppression, and the people don’t believe it. God literally shows them the answer to their prayers, and they shrink back and say they don’t want it. God ransoms them out of Egypt, and they immediately turn, wanting to go back rather than step out in faith, trusting where God is leading them.

It is here in the story that they find themselves pinned against the sea, with nowhere to go, and so they finally resort to calling on God because they have nothing left to do.

They always had nothing from God, but it is finally here that we realize it.

Corrie Ten Boom once said that so often, we treat God as our spare tire rather than our steering wheel.

Despite all the progress of history, there is a problem in the human heart: We resist God’s new way and so often only call on him when we have exhausted all our own strength.

And yet, God, in his mercy, delivers them. Because, says Paul, even if we are faithless, he is faithful, for he cannot deny himself.

God delivered them not because they were worthy but because God has made promises based on his character of love and mercy that he will see done, despite empires and armies, despite sin and death, and despite our stubbornness too.

And so, the exodus story points to something greater than itself: a final and definitive exodus, a moment when sin, death, disobedience, despair, and the devil are shown to be finally defeated.

In the New Testament, Jesus comes, God’s own son, God Immanuel, the True Moses. Jesus comes and heals and helps people. He preaches the coming kingdom of God imminent to us. He enters Jerusalem, and it seems people are ready for him to be king. And on the night of the Passover, celebrating the Exodus, Jesus says that through him is a new covenant. Through his body and blood, we will have a new relationship with God, a definitive display of salvation from our sins: a new and true exodus.

As the Gospels show, Jesus’ promises are met with some of the worst displays of human faithlessness. This is important because for the exodus story to apply to us, we need to place ourselves in the seats of the disciples. And what did the disciples do? They failed just as we failed. The Gospels show the full extent of our enslavement to sin.

Judas betrayed. Peter denied. The others fled in fear, afraid of soldiers such that they deserted the one that could raise the dead. The law of God was manipulated to execute their own deliverer. The people of God were complicit in the murder of their messiah. Jesus was handed over to the Roman legions to be executed on a Roman execution cross.

And in these dark moments of the very worse of human unfaithfulness, Jesus shows us the true Exodus.

Jesus prays in the midst of all this for us: “Father, forgive them. They know not what they do.” His body, which we broke, was broken for us. The blood the people of God shed, he counted as a sacrifice for their sins. By his wounds, we are healed.

No vast sea was split the day Jesus was nailed on the cross, but the veil was torn, and a greater cosmic event occurred: The gulf between God and the sinner was bridged. God embraced death so that we could have life. God chose to suffer as one cursed so that all who cry out forsaken would know God is on their side.

And as the Gospels say, here the Scripture was fulfilled. To read Exodus through the cross is to know that Jesus died for Pharaoh just as much as Moses. Just as Jesus died for Peter, who denied him, he died for you and me, that failed to follow him.

To read this narrative of Pharaoh being thrown into the sea with his soldiers through Christ is to realize that Jesus fulfilled this by accepting that punishment for evil on himself, not visiting it back on those that deserve it, ending the spiral vortex of hate and violence we so often get trapped in.

To read Exodus through the cross is to know that God’s way of dealing with evil is not by bringing disaster on the perpetrators but by bringing healing, with waters not of the Red Sea’s destruction but of baptism’s cleansing. God’s way is not repaying evil with evil but overcoming evil with good.

To read the Exodus Passover through Jesus shows us a God that does not want to kill his enemies, but rather a God who loves his enemies and overcomes them not with force but with forgiveness.

At the cross, the great evils of this world that nailed Jesus to a Roman execution pike did not prevent our Savior from being fully obedient to the Father and fully willing to forgive us. That is how evil was defeated.

And three days later, the Father raised Jesus from the dead, overturning history’s judgment and injustice.

The resurrection was the overturning of death itself. Death, all the drives towards death that sin causes, whether hate, greed, idolatry, deception, or cowardliness – death in all its forms was overcome that day. Humanity’s deepest slavery, the slavery within our very hearts, in the very being of things, was defeated.

“Both horse and driver / he has hurled into the sea,” the text says.

Or, as the early church prayed, “Hell reigns, but not forever.”

Oppression still exists, but its days are numbered.

Death reigns, but it realizes now it is the one that is mortal.

Sin still inflects us, you might say, but there is a vaccine.

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

So, as Moses says, “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today.”

The question for us today is what will it take for us to fully trust God’s Exodus in our lives?

What will it take for us to open all the windows of our souls to let God’s resurrection light in?

What will it take for us to finally say, “I’m done living in Egypt. I am done living Pharaoh’s way here in Canada. I am done with the status quo, this system of slavery that does not work. I am ready to walk with God to his promised land”?

Let’s pray…

God of Exodus hope and liberation.

We look out at our world, and we see that it does not reflect your kingdom. We see such inequality. We see wars and famines and poverty and cruelty. God, it is so overwhelming to think about. So often, we just go along with it out of a sense of defeat and hopelessness.

God, forgiveness our own complicity in the injustices of this world. Wake us up to all the ways we are privileged at the expense of others. Convict us of all the ways to choose the slavery we are in. God forgive us and deliver us.

God, heal our hearts of sin. Renew us with your Spirit so that we will have the freedom to break free from the cycles of sin we are caught in. Empower your church to be a glimpse of your coming kingdom, where hate is overcome with understanding, where anger is overcome with peace and forgiveness, and where pride and privilege are overcome with service and humility. God, show us the liberation of your love.

We long for what your word promises: the restoration of all things. We long for your kingdom to come; your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. We long for a place where righteousness is at home. God gives us the courage to embrace these realities today, to step into the Exodus of new creation now.

These things we pray, amen.

“God’s Victory over (Our) Evil” A Sermon for the Ecumenical Unity Service 2018

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice” – Martin Luther King

From the second book of the Bible, we are given a powerful story.

That God’s people came to the land of Egypt under the protection of Joseph, the long lost son of Jacob, who secured the prosperity of the land against terrible famine, all because he interpreted Pharaoh’s dreams. But after many years, the Israelites multiplied and the Egyptian Pharaohs grew forgetful of who Joseph was and what he did for the Egyptian people years ago.

So, a tyrant Pharaoh arose, who turned and enslaved the Israelites. He forced them to build its temples and pyramids from bricks, hearkening back to the tower of babel. In Scripture the figure of Babylon, the idolatry of empire itself, has many names: Assyria, Greece, Rome, Egypt.

Empires always put power before people. Empires always but money before humanity. Empires always justify terrible oppression as maintain order.

Pharaoh worried that the Israel were getting too numerous for their Egyptian overloads to contain, and in order to keep Egypt pure and powerful, he ordered the genocide of all the baby boys of Israel.

The narrative tells of one boy, Moses, who survived the genocide by being floated in a reed basket down the river, to be picked up providentially by Pharaohs daughter and raised as her own.

This boy, Moses, grew to be a man, and when he learned of the truth about who he was and what the pharaoh had done, murdered a slave master, and fled into exile.

Moses’ outrage tried to solve oppression with violence, and it did not work. Violence never ends violence.

In exile one day he happened upon a mysterious burning bush. It was ablaze but was not consumed. The mysterious sight spoke to him, identifying himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, that he had heard the cries of the people in slavery, and was now going to act.

What shall I call you, Moses asks? “I am that I am” the presence answered. The un-nameable, uncontrollable, freedom of being and root of all existence itself, the Great I Am, this being is on the side of the poor and the oppressed.

Moses is commissioned reluctantly to go and tell the new Pharaoh, his half-brother, that God wants him to let his people go. God wants liberty for his people. God want liberation for all people.

Pharaoh, who believes he is god, refuses, and so Ten Plagues rain down to break the tyrant’s resolve. First the sacred Nile turned to blood, then frogs and lice spread, then disease and boils, hail and locusts, then finally darkness covered the land, and then it says that Pharaohs’ resolve was finally broken in the Passover as the angel of death himself descended and visited the death of the firstborn boys back against Egypt.

Pharaoh finally relented and allowed the Israel to go. But as they left, however, he recanted.

He assembled his army to re-enslave the people and slaughter them if need be. The people fled and then found themselves pressed up against the sea, nowhere to run. No weapons to fight, no soldiers or chariots. All hope was lost.

But then as the story goes, God opened up the sea, walls on either side, dry land in the middle, so that the Israelites could escape.

The Egyptian army rallied to pursue, but as they made their way into the divide, God let go the walls of water, washing the army away.

The Israelite slaves were now free, free without every picking up a sword on their part, free to live, more importantly, free to worship and follow their God.

So, Exodus 15 recites the praise of the people for God rescuing them.

I will sing to the Lord,

for he is highly exalted.

Both horse and driver

he has hurled into the sea…

The Lord is my strength and my defense;

he has become my salvation.

He is my God, and I will praise him…

The Lord is a warrior;

the Lord is his name…

Who is like you—

majestic in holiness,

awesome in glory,

working wonders?

Our readings for this unity service looks at the God we worship (Ex. 15, Psalm 118, and Mark 5). God who is strong, majestic, holy, awesome in glory. It is this very God that is on the side of the weak and the oppressed. It is this very God that opposes the proud and will brings down the powerful. It is this very God who has promised to end the presence of evil in this world.

This is important to say that this story is more about who God is than about the spectacle of walls of water crashing down on unsuspecting Egyptian soldiers. Hollywood loves to fixate on the imagery of chariots and walls of water, whether Moses is played by Carleton Heston or Christian Bale, but Hollywood often forgets the theology.

Martin Luther King said it best:

The meaning of this story is not found in the drowning of Egyptian soldiers, for no one should rejoice at the death or defeat of a human being. Rather, this story symbolizes the death of evil and of inhuman oppression and of unjust exploitation. (King, Strength to Love, 78)

This is a narrative that we see through Christ as we look at evil in the world, which reminds us of God’s ultimate victory over evil and how we are invited to live that out in part today and awaiting a final day of God’s liberation.

1. There is real, radical, systemic, and cosmic evil in our world today.

One might think this is an obvious point. Just turn on the news and you are bombarded with messages about corrupt politicians, poverty, wars and disasters.

But why do we think anything is or can be evil at all – and not just merely unfortunate?

Again, this seems obvious but just as God has become a suspect belief today, so with him, also the belief that there is actually good and evil.

One atheist Neuroscientist wrote that empirically there is no good or evil technically, just nature that we prefer and nature that we don’t. The world, disasters and death is neither moral or immoral. It just is. As far as human nature, there isn’t evil or good, so much as proper functioning brains and malfunctioning brains.

Coincidentally, he is not to big on the idea that humans have free will either.

Our culture has placed its trust in the power of the empirical, and as a result, with belief in a transcendent God out of the picture, so also, slowly with that good and evil.

The world as it is is all there is. It is not evil or good, it just is.

Why is there meaning as opposed to meaninglessness?

Why is sacrifice more virtuous than comfort and apathy

Why is compassion preferable to domination?

Why is good preferable to evil?

Why is life preferable to death?

We are learning that these cherished hopes we have as humans and more specifically as Christians, they are not natural givens. They are not sitting there obvious to the disinterested observer. They are seen by faith. They are produced within a particular community that looks to God for what is most true and meaningful, most ultimate and good.

It is faith in a God, who made the world good, that we know that there is a primal innocence and beauty residing in all reality, and that as humans have made the decision to rebel and reject God’s life and goodness, evil and sin has deformed our world.

Some might say God obviously does not exist because of all the evil in this world. I think it is the opposite. We can only see that there is something called evil in this world by believing there is something good beyond the world.

If God exists and God is good, we know is not the way it ought to be.

2. When we consider evil in our world, we have to contend with the evil within us.

When we know God’s will is goodness, truth, beauty, life and hope, then we look at the world and see that it has radical, systemic, and cosmic evil.

But when we say there is something wrong with the world out there, the scriptures us push to turn our attention from the evil out there to the evil in here, in our hearts. The in excusable evil we do.

This evil is found in the capacity of human beings that in light of all our education and knowledge, all our collective wisdom and arts and religion, and all our power and technology we will still choose the path of annihilation, knowing full-well its harm.

When we know the vast waste and depravity of violence, we still go to war.

When we know that more is accomplished in unity, we choose division.

When we know the benefits of facing hard realities, we still choose to cling to our delusions.

In this story of Israel and Egypt, if we are really honest, we must realize that we are more often Egypt than Israel.

So often we read the Exodus story saying we are the Israelites in a spiritual bondage. The reality is we are more accurately the Egyptians. We are more often oppressor than oppressed. We are members of one of the wealthiest nations on the planet.

We sometimes smugly accuse our neighbors to the south of injustice, but we Canadians have to realize our own nations sins.

Our corporations have stripped the resources away from people in South America and Africa.

Our banks have suffocated the economies of many Caribbean Islands.

We have used our military to even overthrow democratically elected leaders and even Christians leaders in other countries, all to secure our wealth.

I am no internet conspiracy theorist. These are all facts in plain sight. The question is do we have eyes to see these realities?

Underneath our facade of a nation of peacekeepers and human rights is a disappointing track record of exploitation that we Canadians turn a blind eye to because we don’t want to know where our products come from or what is ensures our economic comforts.

We are more like the Egyptians then the Israelites. Many good Egyptians of conscience probably sat ideally by as Israelites died building temples and pyramids. They probably did the same thing we are going. Throwing up our arms and saying, “Oh, well,” and turn a blind eye because they did not want to sacrifice their comforts..

To be human from the standpoint of faith is to know we have a primal goodness, but also the terrible capacity to forsake that goodness.

We as Christians know that while our faith pushes us to love more and pursuit truth more and justice more, but we also are aware that our hearts can also contort our religion into instruments of apathy and self-righteousness.

We do this when we offer prayers that we don’t intend to act on.

We do this when refuse to reach out to the broken in our communities.

When we cling to our own comforts rather than living sacrificially.

When we shut out the world so that we don’t have to have compassion on it.

We look out at the world and we condemn its evil, we look at our country and we realize we are living in a modern day Egypt. And they we look at our churches and we have to realize we are no better.

3. God’s answer to evil, our evil, is the cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ

What happens when we see evil in this world and we realize that we also have that same evil within our hearts? What do we do when we realize we are more like Egypt than Israel?

The book of exodus is a narrative that gets retold, recited, and re-enacted throughout the Bible, particularly the New Testament. If we don’t read the Exodus through the New Testament we are left realizing we belong drowned in that sea rather than safe on that shore. We deserve sorrow not these songs.

But Jesus fulfilled the Scriptures. Jesus is our exodus. Jesus shows us true exodus.

This story of Passover is re-enacted and fulfilled in the last supper and the cross.

This is important because for the exodus story to apply for us, we need to place ourselves in the seats of the disciples. And what did the disciples do? They failed just as we failed. They turned from Jesus. And so often we do to. The disciples that ate with Jesus, knew what was good more than anyone else, they sinned. That is the beginning of the church.

Judas betrayed. Peter denied. The others fled in fear. The people of God were complicit in the murder of their messiah. The law of God was manipulated to execute to their own deliverer. To see radical evil in our world and in our hearts, we need not look any further than what happened to Jesus at the cross by those whom he came to save.

The world denied Jesus, but the more troubling part is that we denied Jesus.

And so, the words are ever more powerful that on the night of the Passover, the night the disciples remembered this exodus event, this was the night Jesus was betrayed, Jesus became our the Passover lamb, to liberate us from our own sins.

His body that we broke, was broken for us.

The blood the people of God shed, he embraced as a path to forgive them of the very sins they were sinning against him. A new covenant.

No vast sea was split the day Jesus was nailed on the cross but the veil was torn, a greater cosmic event occurred: God forgave his enemies, us, God atoned for sins, our sins, even as we murdered him. God embraced death so that we could have life. God chose to suffer as one cursed so that all who cry out forsaken would know they are not.

And as the Gospels say, here the Scripture were fulfilled.

To read exodus through the cross is to know that Jesus died for Pharaoh just as much as Moses. Just as Jesus died for Peter who denied him, he died for you and me that fail to follow him.

To read this narrative of Pharaoh being thrown into the sea with his soldiers through Christ is to realize that Jesus fulfilled this by accepting that punishment for evil on himself not visiting it back on those that deserve it.

To read exodus through the cross is to know that God’s way of dealing with evil is not with bringing disaster on the perpetrators but by bringing healing.

To read the exodus Passover through Jesus shows us a God that does not want to kill his enemies, but rather a God who loves his enemies, overcomes them not with force but with forgiveness, such that even the Roman guards by the cross cried out, “Surely this man was the son of God.”

At the cross the great evils of this world that nailed Jesus to a Roman execution pike did not prevent our Savior from being fully obedient to the Father and fully willing to forgive us. That is how evil was defeated.

And three days later, the Father raised Jesus from the died, overturning histories judgment.

The resurrection was the overturning of death itself. The weapon of evil and fear, empire and tyranny was disarmed that day.

Both horse and driver

he has hurled into the sea.

Jesus overturned our sins that day too. He appeared to those that betrayed him, the disciples, and announced peace to you.

Death, sin, and despair have lost. They destiny is oblivion, and our destiny is liberation.

When we lose hope in ourselves, when we are overwhelmed at the sin in our hearts, we know that we worship a God that would gladly accept the death penalty in order to bring us to him.

When we look at our world, its systems of oppression and corruption, the cogs of death that keep turning, we know we worship the God of life, who raised Jesus from the dead.

Hell reigns, but not forever.

Oppression reigns but its days are numbered.

Death reigns but it realizes now it is the one that is mortal.

Sin is here but it has been defeated.

Christ has had his definitive victory that Easter morning for the tomb was found empty. The grave could not contain him.

Both horse and driver

he has hurled into the sea.

The question then is how to we live this victory?

4. How do we live out the victory of the resurrection?

We are called to sacrifice. When we know that God has given us salvation and the enduring presence of his love, we take our liberation and use our freedom to take up our cross. No one is liberated until everyone is liberated. And the highest freedom is not material mobility but spiritual strength. That is only possible by follow Christ no matter what.

Martin Luther King knew this. Oscar Romero knew this. Maximilian Kolbe knew this. Jim Elliot knew this. All the martyrs that have given their lives for Christ, the Gospel and his kingdom of truth and justice will tell you this.

There can be no path to resurrection without the cross just as there cannot be any path to freedom without sacrifice. And this sacrifice is freedom.

We must be sorry. This freedom begins in repentance. There is no solution to the terrible evil in this world until we take responsibility for our own roles in further it. We are called to acknowledge that we sin and we need forgiveness. We repent because we need restoring.

The Gospel gives us that counter-intuitive truth that humility is liberation. Liberation from ourselves.

We are called to serve. The only way our world will become a better place is by good people acting differently. For use to move out of our culture’s default setting of selfishness and apathy and ignorance.

As Desmond Tutu said, God has no body but ours. God has no hands and feet but ours. God uses our eyes to look upon the oppressed. He uses our ears to listen to those suffering.

Are we, brothers and sisters from different traditions of Christianity, ready to be Christ’s body again?

Lastly, tonight, we are called to sing. That is what we are doing today at this unity service. When we worship a God of perfect goodness and power and love, we see the world differently. If we don’t continue to meet together, to pray together, to recite Scripture together, we will grow weary along the difficult path disciples must way.We need each other.

When we worship together in the unity of Christ, we show a divided world that there is hope beyond the fragments.

And so, please stand with me and let us renew are hearts by praising our God with this inspiring song, “The Right Hand of God.”