Tagged: Resurrection

Resurrecting (the) Text: The Ending(s) of the Gospel of Mark and the Choices We Have to Make

16 When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James and Salome bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. 2 And very early on the first day of the week, when the sun had risen, they went to the tomb. 3 They had been saying to one another, “Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance to the tomb?” 4 When they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had already been rolled back. 5 As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed. 6 But he said to them, “Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. 7 But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you.” 8 So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

The Shorter Ending of Mark

[[And all that had been commanded them they told briefly to those around Peter. And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.]]

The Long Ending of Mark

[[9 Now after he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons. 10 She went out and told those who had been with him, while they were mourning and weeping. 11 But when they heard that he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it. 12 After this he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country. 13 And they went back and told the rest, but they did not believe them. 14 Later he appeared to the eleven themselves as they were sitting at the table, and he upbraided them for their lack of faith and stubbornness, because they had not believed those who saw him after he had risen. 15 And he said to them, “Go into all the world and proclaim the good news to the whole creation. 16 The one who believes and is baptized will be saved, but the one who does not believe will be condemned. 17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: by using my name they will cast out demons; they will speak in new tongues; 18 they will pick up snakes, and if they drink any deadly thing, it will not hurt them; they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.” 19 So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God. 20 And they went out and proclaimed the good news everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by the signs that accompanied it.]]

Gospel of Mark, Chapter 16:1-20 (NRSV)

Introduction: Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Novels?

The 1990s was a good decade to grow up in. The fashion, the TV sitcoms, the video games–it was a good time to be alive.

There is something about this golden age of humanity that also birthed the greatest literary innovation since ink was set to paper. The choose-your-own-adventure novel.

Sure, the high Middle Ages had the Divine Comedy. European modernity had Proust, and Russia its Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. But none can compare to the literary genius of a novel where the reader actually gets to choose how the story is going to unfold. For instance:

You are camping in Connecticut, and as you hike through the woods, you stumble upon a magic orb. Do you (a) turn to page 5 and pick up the orb (causing you to be sucked through a portal into a world with mythical creatures? Do you (b) turn to page 10, leave the orb alone, and continue walking, all to find that you are captured by a dark lord who is looking for the orb? Or, do you (c) turn to page 25 and smash the orb, which, if you choose that course of action, causes the alternative dimension you would have been sucked into in Option (a) to apocalyptically appear around you in your dimension.

As the story goes on, choice after choice, by the end of the novel, you might end up (a) defeating the dark lord, becoming the hero of the universe, (b) joining the dark lord as his apprentice and enslaving the universe, or (c) stumbling upon another magic orb that resets everything back to what it was before, and you find yourself back walking along in the woods as if nothing happened.

If that isn’t literary brilliance, I don’t know what is!

Well, when it comes to today’s passage, let’s just say I have had a few adventures with it, but not the chosen kind.

I remember sitting there reading the Bible during youth group bible study when I was in high school. We were doing a study of the Gospels, and it was coming to an end. We were looking at the passages about the resurrection. Doing this, I could not help but notice that in the Gospel of Mark, there was a strange set of subtitles, marking the “Short ending” and the “longer ending” as well as a further footnote that marked, “Some manuscripts also include this in verse 14.”

I remember turning to my youth leader at the time and asking, “What is going on with these endings? Are there parts of the Gospel that aren’t original to it?”

The youth leader looked at it, seemed puzzled (as if he had never noticed this before), and said, “Maybe Mark wrote two endings and couldn’t decide which one he liked best, so he put both in.”

“Really?” I asked, also puzzled. The leader wrote it off with a joke, “Ha! It is kinda like the end of the Gospel of Mark is a choose your own adventure novel!”

I admit that answer did not satisfy me. But like most awkward and somewhat traumatic instances of my childhood faith, they do end up, at the very least, serving as good sermon illustrations.

Likening the ending of the Gospel of Mark to a choose-your-own-adventure novel–despite my undying love for that under-appreciated genre–did not make sense of the multiple endings.

But there is a quintessential insight from the genre that is true about the life of faith and about our responsibility in reading the text: Faith is often about the choices you make. This text very pointedly compels you to make decisions.

Admittedly, some texts are fairly easy to interpret. We know and love these passages. Other passages are less so. There are biblical texts I have come across that, when we encounter them, we don’t know what to do with them. They do not fit our paradigm. In fact, we get a whiff intuitively that if they mean what we suspect they mean, that possibility is scary and potentially costly.

What do you do? Do you (a) feel overwhelmed and so you turn the page, don’t think about it, try to forget about it, and go on to something more familiar, (b) go online to your favourite website that has all the answers neatly packaged and quickly find the pat answer that solves the problem (or least makes it feel solved for you), or (c) say to yourself, there is something here and “I care enough about God’s Word and the pursuit of truth to think about it and do the hard, boring, and risky work. And who knows? Maybe I may feel called to go on and do my MA at Acadia; I don’t know.”

That last part was a shameless plug, but the question is will we do the difficult work of questioning our assumptions when we are confronted by difficult texts?

And if I am going to be honest here, I chose path (a) for the longest time. You get busy with things. You only have so much time, and so you find yourself gravitating to the things you can handle, thinking about the topics that are manageable. And yet, certain watershed moments are inescapable. Eventually, you will have to make a choice.

“How am I going to preach this?”

Several years ago, I was serving as the pastor of First Baptist Church of Sudbury, but I was also the chaplain and a professor at Thorneloe University. I was asked to supervise a course in the undergrad on the Gospel of Mark that was in the academic calendar. So, I set out to read up on the subject, and I got a stack of commentaries out from the library. Seeing that life was quite busy, I thought the best thing to do was to double up on my teaching with my preaching schedule. So, from New Year’s to Easter, the winter semester, I taught that course, and I also preached the Gospel of Mark.

I admit I would never have preached on the Gospel of Mark. Like many throughout church history, I preferred Matthew and Luke because they were longer and fuller. If I can name it: There is something about the simplicity of Mark that always bothered me. It just wasn’t enough.

In the preaching schedule, I had the crucifixion and resurrection passages for Good Friday and Easter, obviously, but I figured I would deal with these final verses the week after. I remember thinking about these verses, unsure how I would tackle them, but figuring I would work it out like all the other weeks as I go.

Well, teaching and pastoring, as you can imagine, was very busy. Good Friday and Easter came, and then, I remember coming into my office, still exhausted from the weekend, sitting down at my desk, looking at this text with a stack of commentaries next to me, and asking myself, “How am I going to preach this?”

Do I (a) skip it and just start the next preaching series one week early? That transition from Easter to a new series makes sense. Do you think anyone would notice?

Do I (b) preach on just the definite ending, ending at verse 8, not treat the rest, and maybe if one of the more astute and inquisitive congregants asks me about it after, then I can have a conversation with them?

Do I (c) read the whole thing but ignore the tough issues of the text or say that we just don’t have time to get into all that this morning and instead just focus on some moral application to be drawn from the story?

I did not know what to choose. I immersed myself in the commentaries, hoping an answer would emerge. Writer’s block quickly set in as I kept wrestling through the different perspectives. I remember asking myself, “How do I preach a text I haven’t made up my mind on? How do I preach a text that I am not even sure should even be a text at all? How am I having this dilemma? I’m the pastor. I have a doctorate in theology from a prestigious university. I am supposed to know the answer. Isn’t that what my job is?

What if people get upset at this? We got some folks that started coming to our church from the fundamentalist church the next town over. Would they leave over this?

What about that person that seems really fragile in their faith, that person who comes to church needing encouragement and not more questions? Will this sermon burden them? Am I being unpastoral for preaching a sermon on this stuff? If I believe that, am I admitting that it is somehow a good thing to keep what is going on in the Bible from some people? Is that what good preaching is?

Well, as some of you may have found in your pastoral ministry, Saturday night has a way of sneaking up, and I tried desperately to piece together something to say. I resolved an option (d): perhaps the best approach was not to tell the congregation what I thought was the answer (because, in truth, I was not sure myself) and just lay out the options in bare honesty and let the congregation decide for themselves.

Well, as I did that Sunday morning, I announced that it looks like there are three sets of options: There is the question of how to interpret the original ending; the question of the longer and shorter ending; and the question of what to do with them, overall.

The Original Ending: Incomplete or Cliffhanger?

All agree that the earliest manuscripts have the announcement by the angel at the empty tomb that Jesus is risen, and the women leave afraid, ending in verse 8. Then what?

Option (a): some commentators believe perhaps Mark did not finish his Gospel or the manuscript was broken, torn, or lost and, either way, it was circulated in its incomplete form.

One reason given for this is that the last line, which in most translations reads, “and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid,” the last word of the last phrase there is “gar,” the Greek word for “for” or “because.” Some have suggested that it is very unlikely the Greek would end that way, implying a break in the language, literally reading something like, “They were afraid because….” and here the manuscript breaks off or Mark was not able to finish.

Well, that’s possible, but then there is Option (b): other commentators say that while it is unlikely to have the line end on gar, it is not impossible, and perhaps the Gospel of Mark intentionally ends here. After all, there is a consistent theme of people being amazed and fear-struck by Jesus’ miracles. There is also the theme of secrecy in Mark, where Jesus tells people not to tell anyone, and yet, lo and behold, in the last irony of the Gospel of Mark, the witnesses leave, commanded to tell the other disciples, and they are speechless.

In other words, Mark ends his Gospel with a kind of ironic cliffhanger ending, but the very fact that Mark is writing what he is writing to churches decades later attests to the obvious fact that the women did not remain silent, telling others the Gospel.

So, you are left with the options of either (a) the original was broken off or (b) it intentionally ends with a cliffhanger ending.

Either one leaves us with some discomfort: either the text we have is incomplete or damaged, or it is quite minimal: no actual post-resurrection appearance, only a promise to the women that when they go and tell others, they will meet the resurrected Jesus on the way.

The Added Endings: Shorter or Longer?

Well, whatever you think about how the original ending, there are more choices to make: What do we do with the added Short and Longer endings? Again, here are the options:

Option (a): Well, the shorter ending is actually the more recent ending, and the first time it pops up in the manuscripts is in the fourth century: “And all that had been commanded them they told briefly to those around Peter. And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.”

Actually, the “Amen” is not in the earliest version of this addition. Apparently, one copyist really loved his ending and couldn’t help by writing “Amen” at the end, which might have been an ancient way of hitting the like button.

Why was the shorter ending put in? Some speculate as to its theology: It mentions the importance of Peter and the Gospel reaching east to west. This sounds like a description of the emerging Christendom in Europe in the fourth century, with Rome consolidating its power around its claim to the office of Peter.

As one commentator notes, it seems like more than a coincidence that we see neater, more definitive, even triumphal, endings getting placed on the bare, bewildering, response-begging ending of the original and that this happened around the time Christians moved from a marginalized, powerless community to the community in power.

If the original does end at verse 8, is the Shorter ending an imperial rewrite trying to stabilize Christian readers with certainty where Mark wanted to destabilize in order to provoke a response? That is up to you to decide.

Let’s move on to Option (b): The longer ending is actually older. It dates to the late second century (and even then, there are different versions of that one). If you look at the more common version, it appears to be a set of summary statements gleaned from the end of the Gospel of Luke. And so, we can speculate, possibly one well-intended copyist tried to paste an abbreviated version of Luke onto the end of Mark to make sure anyone reading Mark would know there is more to the story. Perhaps they were trying to be pastoral, trying not to burden the readers with too much disruption.

Well, whatever the case, this version over the other ending becomes the dominant version used in Western Bible translations. And thus, it is assumed as the original ending in the King James Version and others during the time of the Reformation. It was not until the 1800s that manuscript comparisons made it obvious it was not original and that there were more than one ending.

Take Them Out or Leave Them In?

Well, here is the next set of choices. Knowing all that we now know, what should we do with these endings? Again, options put us between a rock and a hard place:

Do we, Option (a), take them out of the Bible?

Well, take it out, and we have the uncomfortable admission that the text we have had in hand, the text we have had and used for about 1800 years, that Christians have read, preached, and claimed to have heard God speak through, was corrupt, so much so that it is in need of fixing, on a passage of no lesser importance than the conclusion of the first Gospel. That’s kind of important.

Do we take it out? Is it our obligation to take it out? Evidently, most translations still leave it in. Many try to minimize the multiple versions and try to present the ending as smoothly as possible. Why? Probably because of marketing. Most Bible translations still cling closely to the KJV because that is the wording that so many have an attachment to.

Do we take it out? If we choose to take this out, should we do that with other passages or even books of the Bible? Should we take the story of the woman caught in adultery out? Should we take the possibly inserted line in 1 Cor. 14 about women being silent out? Should we take out the books some scholars think the Apostles did not actually write? Why stop there? Or maybe we should add back in some stuff, like the books of Enoch or the Gospel of Thomas or the Apocalypse of Peter or, or, or… Well, good luck with that.

Certainly, some of these examples are more extreme than others, but the question is, in the interest of trying to get back to just what the original authors wrote, where do you draw the line? Can you draw it in some circumstances?

And does trying to fix the text ironically send us down the same path that motivated some well-intended folk to put an extra ending on the Gospel of Mark in the first place?

Perhaps we have to confess that we are left with a text in hand that doesn’t really fit our perceived expectations of what the Bible ought to look like and perhaps was never meant to.

So, there is Option (b): leave the endings in.

If that is your choice, you are presented with some other challenges (not least of which is the question of which ending to leave in or possibly both).

How do you see inspiration working between the text and its author (or, in this case, authors)? Is only what Mark wrote inspired? Are we compelled to believe that the writers of those other endings, whoever they are, were inspired as well?

Can we say that we trust that God has indeed spoken through these words and continues to speak through them? Have believers legitimately heard the voice of the Spirit speaking through these other endings for 1800 years?

Does that commit us to the theology of these passages? Some have invoked the other ending for their practice of snake handling under the promise of divine apostolic protection (Look that up on Youtube¾as if there isn’t enough emotionally scaring material on the internet already). And if ever tempted to think this conversation does not matter or is too heady to think about, say while watching a pastor shouting these verses while twirling a cobra around, all to have that cobra bite him in the face. Let’s just say it puts things in perspective.

But that means we are left with uncomfortable options: Did human error and human fallibility adulterate the ending of Mark, or did God, for some reason, allow this to happen, superintending it? But why would God do that?

“The Medium is the Message”

Well, whatever you decide on that, you are faced with questions about the text in hand: Can a text speak beyond what has been said, how it was said, what has been done to it? Can God speak through a text that we have doubts about? Can God speak through a text that we might not even think should be the biblical text at all? What does that say about the nature of God’s word? What does that say about faith?

In high school, we had to do a unit on media. One Canadian philosopher named Marshall McLuhan said something that got repeated over and over. Let’s see if you remember his famous line: The medium is the ______ (message). Flashback to grade 12 English class.

If the medium is the message, this text, its many endings, and its evidence of additions say something about what faith is and what we have faith in.

We sang a song in Sunday School: “The B-I-B-L-E, yes that is the book for me, I stand alone on the Word of God, the B-I-B-L-E.” I love that song. Well, to be a Christian is to trust what the Bible says. But what if the Bible, whether by incident or perhaps even by design, does not, in some cases like this case, give us an easy place to stand?

If you feel like these options do not give you an obvious decision, maybe that is where God’s Word wants you to be. What if the faith that the Bible demands is much riskier? What if the Bible intends us to do something more like take a leap rather than stand still?

Because if it was perfectly black and white, seamlessly clear, unquestionable and certain, would it be faith? It certainly wouldn’t be a relationship where honesty and vulnerability are integral.

There is something about the Bible that beckon us to be responsible interpreters, free and active participants in conversation with God rather than fearful and passive recipients. Good Baptists might call this soul competency or soul liberty. And if this is the case, the options of this text remind faith–by that, your faith, my faith, yours and no one else’s, mine and no one else’s, not how we were raised, not the beliefs of our community, not what you were taught in seminary–that faith in order for it to be yours has to responsible. It must contend with open ended-ness, ambiguity, even brokenness, to choose to walk with God in and through these rather than using faith to somehow insulate us from the obvious fact that we are human, finite and frail, and there is no thought we have, whether read off the page of sacred texts, given by an ecstatic vision, decided by magisterial proclamation, or deduced with all the prowess of academic evidence and reason that escapes this permanent fallibility. And if that causes discomfort or decentres you, perhaps that is the kind of effect Mark’s ending is trying to produce (whether by the intention of the human author or divine author). Its purpose is not to harm faith but to deepen it.

Does a text like this cause us to doubt the Bible, or does it remind us in its own way where the Bible truly gets its authority from? Does it provoke worry or wonder?

The Bible is not ultimately a choose-your-own-adventure novel, at least not the kitschy ones of my own childhood. But it is a story that finds its highest truth in the choices of its true main character, God, to whom we are invited to respond to. It is the story of God’s Yes to sinful humanity in Jesus Christ. The resurrection is the story in which all other stories find themselves, including our stories of brokenness, if we choose to trust it.

It is the truth that our God is the God who transforms tragedy into opportunity; the God who turns betrayal into forgiveness; the God who turns execution into liberation; and the God who turns death into eternal life.

How do we know this reality? In one way, these endings reiterate our need to trust the resurrection all the more. The juxtaposition is perhaps providential.

As if to say there can be no knowledge of the resurrection without a risky choice. You just don’t know it just by hearing about it, reading it, or arguing about it. It can’t be just an idea in your head. You must choose to follow it, follow it to the point of giving up all you know, follow it to the point of becoming last in this world, follow it despite feelings of fear and uncertainty, follow it to the point of taking up your own cross. The text presents us with this choice:

The choice to live life in the midst of death.

The choice to live in hope in the midst of despair.

The choice to live out love and forgiveness in the midst of hate and violence.

The choice to live in honesty and mercy in a world that is content with lies and arrogance.

The choice to live in trust and humility in the midst of a world that desires power and control.

The choice to keep your life set on the light that shines in the darkness trusting the darkness will not overcome it. As the women found as they left the empty tomb, it is here on this way–if we choose to walk it–walking in Jesus’ way, we encounter what this text is truly about: the resurrection, because he is risen.

You see, if the medium is the message, we must ask: Can God continue to speak through these words? Put another way: Can God resurrect the text? I choose–I am led to believe that the same Spirit that brought breath back to the corpse of Christ breaths through these pages and is breathing on us today: Does God use imperfect believers to be members of the body of Christ? Can God resurrect a broken church? These questions are one and the same, finding their answer in the God scripture witnesses to and we witness to, with the very letters of our lives.

Now it is your turn: as you go from here, what will your choice be?

Let’s pray:

God of the resurrection and the life, we trust you. In all of life’s uncertainty, in all the doubts and questions we have, we trust you. Lead us in the life of resurrection, but remind us that this path is always through taking up our crosses. Remind us that the journey will include dark valleys. Jesus, we know that you never leave us or forsake us. Walk with us today and always. You are our hope, you and no other. Renew us, Holy Spirit, speak to us afresh and breathe life into us when we become exhausted. For your Good News, may we never be silent. For your faithfulness, may we never stop praising you. Amen.

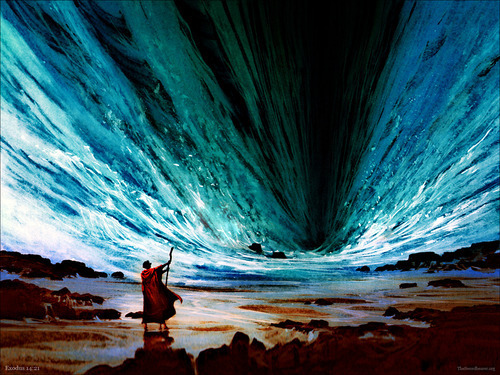

Systems of Slavery and Our True Exodus

Preached at Billtown Baptist Church, January 15, 2023.

The Israelites, a people descending from a man named Abraham, came to live in a land called Egypt due to God working mysteriously and powerfully in the life of Abraham’s great-grandson, Joseph. Joseph was sold into slavery by his jealous brothers, but what they meant for harm, God meant for good, it says, and through these tragic circumstances, God uses Joseph, raising him up to second in command in the nation, and saves Egypt from seven years of famine. In doing so, he is able to provide for his family, who come to live there. Hundreds of years go by, and a Pharaoh arises who knows nothing of what the Israelite hero, Joseph, did, and he decides to enslave the people of Israel, making them work, making mud bricks. He is so threatened by how numerous they are he orders the destruction of newly born boys. One boy, however, is hidden by his mother and sister in a basket, a basket in the water that Pharaoh’s own daughter finds and raises Moses as her own. When Moses grows up and learns of his true heritage, he murders, in his rage, an Egyptian taskmaster and flees in Exile to Midian.

There it seems, he consigns himself to a modest life. He makes peace with the injustices he cannot change. He gets married. He tends sheep. But one day, he sees a spectacle: a burning bush, the divine presence appearing to him. And this divine presence speaks and reveals the name of God, “The I am who I am.” This God, who made promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob long ago, has heard the cries of the oppressed. This living God commissions Moses¾against his choice at first¾to go and tell Pharaoh to let God’s people be God.

Moses goes and talks to Pharaoh. He tells him God is ordering him to release the Hebrew people. Pharaoh’s response? “Who is this God that I should listen to him?”

And so, Moses warns that ten plagues will come upon Egypt, each showing God’s sovereignty over the gods of Egypt, each stripping Pharaoh of his credibility and, with it, the Egyptian resolve.

Finally, after the most formidable of plagues, the death of the firstborn, Pharaoh, relents. The people assemble to leave, and they march out into the wilderness. And this is where our scripture reading for today picks up. I am going to read the whole chapter, Chapter 14, and the first part of 15:

14 Then the Lord said to Moses, 2 “Tell the Israelites to turn back and camp in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-zephon; you shall camp opposite it, by the sea. 3 Pharaoh will say of the Israelites, ‘They are wandering aimlessly in the land; the wilderness has closed in on them.’ 4 I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and he will pursue them, so that I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, and the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord.” And they did so.

5 When the king of Egypt was told that the people had fled, the minds of Pharaoh and his officials were changed toward the people, and they said, “What have we done, letting Israel leave our service?” 6 So he had his chariot made ready and took his army with him; 7 he took six hundred elite chariots and all the other chariots of Egypt with officers over all of them. 8 The Lord hardened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and he pursued the Israelites, who were going out boldly. 9 The Egyptians pursued them, all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, his chariot drivers and his army; they overtook them camped by the sea, by Pi-hahiroth, in front of Baal-zephon.

10 As Pharaoh drew near, the Israelites looked back, and there were the Egyptians advancing on them. In great fear the Israelites cried out to the Lord. 11 They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us, bringing us out of Egypt? 12 Is this not the very thing we told you in Egypt, ‘Let us alone so that we can serve the Egyptians’? For it would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the wilderness.” 13 But Moses said to the people, “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today, for the Egyptians whom you see today you shall never see again. 14 The Lord will fight for you, and you have only to keep still.”

15 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Why do you cry out to me? Tell the Israelites to go forward. 16 But you lift up your staff and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it, that the Israelites may go into the sea on dry ground. 17 Then I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians so that they will go in after them, and so I will gain glory for myself over Pharaoh and all his army, his chariots, and his chariot drivers. 18 Then the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I have gained glory for myself over Pharaoh, his chariots, and his chariot drivers.”

19 The angel of God who was going before the Israelite army moved and went behind them, and the pillar of cloud moved from in front of them and took its place behind them. 20 It came between the army of Egypt and the army of Israel. And so the cloud was there with the darkness, and it lit up the night; one did not come near the other all night.

21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. The Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and turned the sea into dry land, and the waters were divided. 22 The Israelites went into the sea on dry ground, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left. 23 The Egyptians pursued and went into the sea after them, all of Pharaoh’s horses, chariots, and chariot drivers. 24 At the morning watch the Lord, in the pillar of fire and cloud, looked down on the Egyptian army and threw the Egyptian army into a panic. 25 He clogged their chariot wheels so that they turned with difficulty. The Egyptians said, “Let us flee from the Israelites, for the Lord is fighting for them against Egypt.”

26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, so that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots and chariot drivers.” 27 So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at dawn the sea returned to its normal depth. As the Egyptians fled before it, the Lord tossed the Egyptians into the sea. 28 The waters returned and covered the chariots and the chariot drivers, the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea; not one of them remained. 29 But the Israelites walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left.

30 Thus the Lord saved Israel that day from the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. 31 Israel saw the great work that the Lord did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the Lord and believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses.

15 Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song to the Lord

“I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously;

Exodus 14:1-15:3 NRSV

horse and rider he has thrown into the sea.

2 The Lord is my strength and my might,[a]

and he has become my salvation;

this is my God, and I will praise him;

my father’s God, and I will exalt him.

3 The Lord is a warrior;

the Lord is his name.

We can see in history moments of liberation, moments that seem exodus-like: where those things that we see as truly oppressive to people get dismantled or a higher moment of dignity for people is achieved.

In 1945, the allied forces finally overpowered the German forces. Germany surrendered with the tyrant Hitler dead and Berlin surrounded, ending perhaps the most brutal conflict in modern history. War was finally over. People did not need to be afraid anymore. The troops could come home. The nations Germany had taken over were free. News of the victory caused people to dance in the streets.

In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr crossed the bridge at Selma, peacefully confronting a small army of police who had brutalized the protesters days earlier. Walking prayerfully in a line, the protestors were resolute, and in a moment that came to be described as divine providence, the police relented. The protestors continued their march to Montgomery to advocate for voting rights for African Americans. The people on the march sang and praised God. What began as a few protestors swelled to tens of thousands, joining in the work of justice. Within several months they achieved what they were seeking.

In 1989, the Berlin wall was torn down: A wall set up by the Soviet Union to control their chuck of Germany after World War 2, separating families overnight for years. Finally, the wall came down. Many in North America watched their television screens as one segment smashed through, and the people on the other side stuck their hands through. Family members could see each other, touch each other, and, as the segments came down, were reunited in moments of pure joy.

There are many other events that we might describe as exodus-like: like the abolition of slavery, the day women got the right to vote, a country gaining independence, or, most recently for us, the day a vaccine was discovered. If you remember that day, the day you got tangible hope finally that the pandemic would end. These are moments of hope.

Just a few weeks ago, I read in the news that the hole in the O-Zone Layer is shrinking due to the global reduction of the chemicals that caused the hole. It will still take several more decades for the hole to be repaired fully, but with all the bad news on global warming, it was just so encouraging to hear about this little victory.

Each of these moments, no matter how small or even how secular, are pin-pricks of light showing through the shroud that enfolds us, glimmers of what God desires in human history: God wants to establish his kingdom on earth. God wants his will, as the Lord’s prayer says, to be done on earth as it is in heaven. God wants his goodness to heal every facet of this world, setting all that has gone wrong right again without remainder.

That is what this story in Exodus is pointing to. Martin Luther King correctly describes this story when he said this:

“The meaning of this story is not found in the drowning of Egyptian soldiers, for no one should rejoice at the death or defeat of a human being. Rather, this story symbolizes the death of evil and of inhuman oppression and of unjust exploitation” (King, Strength to Love, 78).

Martin Luther King went on to say, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

It is so easy to forget this when we look out at the world we live in. It is so easy to be disenchanted with the notion that God wills the hope of liberation for our world when we are inundated with messages of the world growing darker.

History does not feel like it is bending toward God’s justice. It feels more like one step forward and two steps back (or, in some cases, three or four or even a leap back).

I felt it in 2020 when we were scared in our homes from a pandemic that would come to claim more than 3.3 million people. The globalized world we live in all of a sudden felt so precarious.

At the same time, we in Nova Scotia witnessed a stand-off between indigenous fishermen and settler fishermen in St. Mary’s bay, a stand-off sparked by decades of neglect by the federal government to properly regulate, a clash fuelled by underlying resentment that explored into a racial conflict. And we say the pictures of violent mobs and fires. And I remember saying to myself: “We haven’t come as far as we think we have.” The injustices of the past linger in the present. As soon as people feel their livelihood threatened, good folk turn back to old hate.

We inhabit a world warped by a colonialist past and a present that still has so much exploitation and inequity in it. So many of our luxuries as Canadians, sold in our stores to us, which we thoughtlessly buy, are products made from exploited work or exploited resources from other countries.

When we think about it, we feel caught in this system of the world that simply is not the way things ought to be, and we don’t know what to do about that.

While these systems of greed and exploitation have afforded us westerners comforts that most of the rest of the world can only dream of having, we feel a strange sense that we are powerless in our own way. We feel enslaved to these economic and cultural forces (the “powers and principalities,” as Paul called them) that say to us: “You can’t do anything about this; this is just the way the world works. Get used to it. There is no changing it.”

When we know God’s will is goodness, truth, beauty, life and hope, then we look at the world and see that it has radical, systemic, and cosmic evil: that the world is not as it should be. We feel powerless against this. We feel trapped.

Why can’t we humans get our act together?

When we say there is something wrong with the world out there, scriptures push us to turn our attention from the evil out there to the evil in here, in our hearts. The inexcusable evil we do.

Otherwise, we do something sometimes even more terrible: we convince ourselves we are the righteous few, better than everyone else, the pure ones, God’s favourites among the damnable masses. When we delude ourselves into that kind of self-righteousness, we see history scared with those that felt they could take God’s wrath into their own hands rather than let God fight for us.

It is an old saying that when we point fingers, we have three fingers pointing right back at us.

Society has made advances and progress in many wonderful ways. Yet, it still has not changed the human heart: the same evil capacities remain in human beings that in light of all our education and knowledge, all our collective wisdom and arts and religion, and all our power and technology, we will still choose the path of annihilation, knowing full-well what it is.

When we know the vast waste and depravity of violence, we still go to war.

When we know that more is accomplished in unity, we still choose division, petty feuds and tribalism.

When we know the benefits of facing hard realities, we still choose to cling to our delusions and our comforts.

In this story of Israel and Egypt, if we are really honest, we must realize that we are more often Egypt than Israel. We are God’s people, and yet we live all too happy as people of Pharaoh.

We, as Christians, know that while our faith pushes us to love more and pursue truth more and justice more, we also are aware that our hearts can also contort our religion into instruments of apathy and self-righteousness.

We do this when we offer prayers that we don’t intend to act on.

We do this when we know the beauty of the Gospel and don’t share it.

We do this when we talk about salvation as a way of escaping all our problems rather than confronting them, a strictly spiritual reality that never offends, confronts, or transforms.

We do this every time we settle for an anemic, easy gospel that refuses to look at all the ways sin has its grip on us and, more tragically, all the ways we ignore the offer of eternal life, the fullness of life, the invitation into God’s kingdom because we are content with so much less.

We look out at the world, and we condemn its evil; we look at our country, and we realize we are living in a modern-day Egypt. And then we look at ourselves, and we have to realize we are no better.

We choose our chains.

C. S. Lewis once said it is our perennial tendency to be content playing in filth when God has shown us the path to the most beautiful beach right around the corner.

One ongoing detail of the Book of Exodus is just how much the people gripe and complain. Moses comes and says that God has sent him to rescue them from oppression, and the people don’t believe it. God literally shows them the answer to their prayers, and they shrink back and say they don’t want it. God ransoms them out of Egypt, and they immediately turn, wanting to go back rather than step out in faith, trusting where God is leading them.

It is here in the story that they find themselves pinned against the sea, with nowhere to go, and so they finally resort to calling on God because they have nothing left to do.

They always had nothing from God, but it is finally here that we realize it.

Corrie Ten Boom once said that so often, we treat God as our spare tire rather than our steering wheel.

Despite all the progress of history, there is a problem in the human heart: We resist God’s new way and so often only call on him when we have exhausted all our own strength.

And yet, God, in his mercy, delivers them. Because, says Paul, even if we are faithless, he is faithful, for he cannot deny himself.

God delivered them not because they were worthy but because God has made promises based on his character of love and mercy that he will see done, despite empires and armies, despite sin and death, and despite our stubbornness too.

And so, the exodus story points to something greater than itself: a final and definitive exodus, a moment when sin, death, disobedience, despair, and the devil are shown to be finally defeated.

In the New Testament, Jesus comes, God’s own son, God Immanuel, the True Moses. Jesus comes and heals and helps people. He preaches the coming kingdom of God imminent to us. He enters Jerusalem, and it seems people are ready for him to be king. And on the night of the Passover, celebrating the Exodus, Jesus says that through him is a new covenant. Through his body and blood, we will have a new relationship with God, a definitive display of salvation from our sins: a new and true exodus.

As the Gospels show, Jesus’ promises are met with some of the worst displays of human faithlessness. This is important because for the exodus story to apply to us, we need to place ourselves in the seats of the disciples. And what did the disciples do? They failed just as we failed. The Gospels show the full extent of our enslavement to sin.

Judas betrayed. Peter denied. The others fled in fear, afraid of soldiers such that they deserted the one that could raise the dead. The law of God was manipulated to execute their own deliverer. The people of God were complicit in the murder of their messiah. Jesus was handed over to the Roman legions to be executed on a Roman execution cross.

And in these dark moments of the very worse of human unfaithfulness, Jesus shows us the true Exodus.

Jesus prays in the midst of all this for us: “Father, forgive them. They know not what they do.” His body, which we broke, was broken for us. The blood the people of God shed, he counted as a sacrifice for their sins. By his wounds, we are healed.

No vast sea was split the day Jesus was nailed on the cross, but the veil was torn, and a greater cosmic event occurred: The gulf between God and the sinner was bridged. God embraced death so that we could have life. God chose to suffer as one cursed so that all who cry out forsaken would know God is on their side.

And as the Gospels say, here the Scripture was fulfilled. To read Exodus through the cross is to know that Jesus died for Pharaoh just as much as Moses. Just as Jesus died for Peter, who denied him, he died for you and me, that failed to follow him.

To read this narrative of Pharaoh being thrown into the sea with his soldiers through Christ is to realize that Jesus fulfilled this by accepting that punishment for evil on himself, not visiting it back on those that deserve it, ending the spiral vortex of hate and violence we so often get trapped in.

To read Exodus through the cross is to know that God’s way of dealing with evil is not by bringing disaster on the perpetrators but by bringing healing, with waters not of the Red Sea’s destruction but of baptism’s cleansing. God’s way is not repaying evil with evil but overcoming evil with good.

To read the Exodus Passover through Jesus shows us a God that does not want to kill his enemies, but rather a God who loves his enemies and overcomes them not with force but with forgiveness.

At the cross, the great evils of this world that nailed Jesus to a Roman execution pike did not prevent our Savior from being fully obedient to the Father and fully willing to forgive us. That is how evil was defeated.

And three days later, the Father raised Jesus from the dead, overturning history’s judgment and injustice.

The resurrection was the overturning of death itself. Death, all the drives towards death that sin causes, whether hate, greed, idolatry, deception, or cowardliness – death in all its forms was overcome that day. Humanity’s deepest slavery, the slavery within our very hearts, in the very being of things, was defeated.

“Both horse and driver / he has hurled into the sea,” the text says.

Or, as the early church prayed, “Hell reigns, but not forever.”

Oppression still exists, but its days are numbered.

Death reigns, but it realizes now it is the one that is mortal.

Sin still inflects us, you might say, but there is a vaccine.

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

So, as Moses says, “Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today.”

The question for us today is what will it take for us to fully trust God’s Exodus in our lives?

What will it take for us to open all the windows of our souls to let God’s resurrection light in?

What will it take for us to finally say, “I’m done living in Egypt. I am done living Pharaoh’s way here in Canada. I am done with the status quo, this system of slavery that does not work. I am ready to walk with God to his promised land”?

Let’s pray…

God of Exodus hope and liberation.

We look out at our world, and we see that it does not reflect your kingdom. We see such inequality. We see wars and famines and poverty and cruelty. God, it is so overwhelming to think about. So often, we just go along with it out of a sense of defeat and hopelessness.

God, forgiveness our own complicity in the injustices of this world. Wake us up to all the ways we are privileged at the expense of others. Convict us of all the ways to choose the slavery we are in. God forgive us and deliver us.

God, heal our hearts of sin. Renew us with your Spirit so that we will have the freedom to break free from the cycles of sin we are caught in. Empower your church to be a glimpse of your coming kingdom, where hate is overcome with understanding, where anger is overcome with peace and forgiveness, and where pride and privilege are overcome with service and humility. God, show us the liberation of your love.

We long for what your word promises: the restoration of all things. We long for your kingdom to come; your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. We long for a place where righteousness is at home. God gives us the courage to embrace these realities today, to step into the Exodus of new creation now.

These things we pray, amen.

Can These Bones Live?: The Resurrection of the Body and the Mission of the Church

Preached November 21, 2021, at Brookfield Baptist Church for their 159th anniversary service.

Let me read to you a text of hope for our troubled times. It is a vision of Ezekiel’s from Ezekiel chapter 37:1-14:

37 The hand of the Lord was on me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the Lord and set me in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. 2 He led me back and forth among them, and I saw a great many bones on the floor of the valley, bones that were very dry. 3 He asked me, “Son of man, can these bones live?” I said, “Sovereign Lord, you alone know.” 4 Then he said to me, “Prophesy to these bones and say to them, ‘Dry bones, hear the word of the Lord! 5 This is what the Sovereign Lord says to these bones: I will make breath enter you, and you will come to life. 6 I will attach tendons to you and make flesh come upon you and cover you with skin; I will put breath in you, and you will come to life. Then you will know that I am the Lord.’” 7 So I prophesied as I was commanded. And as I was prophesying, there was a noise, a rattling sound, and the bones came together, bone to bone. 8 I looked, and tendons and flesh appeared on them and skin covered them, but there was no breath in them. 9 Then he said to me, “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, son of man, and say to it, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: Come, breath, from the four winds and breathe into these slain, that they may live.’” 10 So I prophesied as he commanded me, and breath entered them; they came to life and stood up on their feet—a vast army. 11 Then he said to me: “Son of man, these bones are the people of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off.’ 12 Therefore prophesy and say to them: ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: My people, I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them; I will bring you back to the land of Israel. 13 Then you, my people, will know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves and bring you up from them. 14 I will put my Spirit in you and you will live, and I will settle you in your own land. Then you will know that I the Lord have spoken, and I have done it, declares the Lord.’” (NIV)

God bless the reading of his word.

I remember my first day as a lead pastor. This was after several months of applying around, resume after resume, each church turning me down – they did not want to take on a doctoral student, they also wanted someone with more experience.

Life then was so uncertain back then. I was just beginning my dissertation for my doctorate at the University of Toronto. My contract as a coordinator of a drop-in center for those who faced homelessness and poverty in downtown Toronto had ended due to the funding cuts to social programs in Toronto. My wife and I just had our second child, Emerson, a few months prior. We had just bought a home and now were realizing we might have to sell it. My contract as an intern for church planting in another Baptist denomination had come to an unfortunate end: the denominational leaders found out that I was in favor of women in ministry, and for this Baptist denomination, such a belief was beyond the pale. I had a meeting with a denominational leader, a card-carrying fundamentalist, who gave me an ultimatum: he put on no uncertain terms that the belief that men lead (and are the only ones that can be pastors) and women submit – this conviction was for him and the denomination essential to the Gospel, and that meant for me that I had to either shut up or have my funding as a church planter cut. I decided I could not in good conscience continue. It was hard leaving the denomination that my grandfather was a founding pastor of. When you have to leave the church family you were raised in, it feels like you are leaving Christianity itself, since it is the only Christianity you know. When you are literally threatened and attacked by your church family, the one that raised you, attacked over the beliefs you feel are biblical, if you have ever had a similar interaction with some of your Christian friends, it can make you wonder, does the church have a future? If it does, is it a future with me in it?

So, in all the uncertainty, a Canadian Baptist church, the 120 year old First Baptist of Sudbury hired me. They wanted a young pastor. First Baptist Church of Sudbury was a little church four hours north of Toronto, a place I had only visited once when I was in high school in the winter, a place that gets down to minus 40 in the winter, and I wondered how any human being could live here. It was this church that voted to hire me.

All of that is to say, I remember walking into my office to see that the interim pastor had left a report on my desk. It was a church growth flow church, charting the birth of a church, the peak years of a church, and then qualities and stages that indicate decline, and finally twilight and death. There was a big red circle around the word death.

This was a church, as I found, that had experienced over a decade of turmoil to no fault of its own. Two pastors one after the other had really done a lot of damage to the church. One ran off with the wife of one of the deacons. The other was hired and did not tell the church he was going through a bitter divorce with his wife and then divided the church. I remember that summer the church attendance was less than a dozen people.

It was not a very encouraging first day as I reflected how we just moved my family 400 kilometers away to a small church, all of which were twice and sometimes three times my age. Does this church have a future? Does the church have a future?

This is a question I think many are asking especially in this time of the aftermath of the Pandemic. Financially the pandemic has rocked Canada: the Toronto Star has estimated that pandemic has costed Canadians 1.5 billion dollars of every day of the pandemic. For the United States, the total cost to date is estimated to be over 16 trillion dollars. People are worried whether there will be enough to go around.

Yet, it is the human cost that is most important. According to the most recent numbers on John Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Resource Center, there has been 256 million reported cases globally and there has been 5.1 million deaths attributed to the virus. Canada has seen 29 000 deaths. We call that being fortunate, but it is really so, so tragic. Many of these individuals have been seniors in nursing homes and long-term care facilities. But make no mistake: this virus is unpredictably deadly. I heard that a classmate of mine a few months ago, a woman my age with a child, got the virus, went to bed, and did not wake up.

For many, it has been the emotional toll that people have felt the most: feelings of isolation, burn out, anxiety. Churches have felt this as their pastors have been over worked to put services online and adapt to new health standards. All our churches have felt distant from members of the community but also feeling obstructed from doing ministry in the wider community.

As we look out at a post-pandemic world, as it moves to endemic stage, while we are still facing waves and new variants, it feels like we are surveying the wreckage. It feels like we are the survivors of a battle.

In my reading of Scripture, recently I went through the book of the prophet Ezekiel. Ezekiel was a prophet and a priest that proclaimed messages and visions from God about 600 years before Christ. Ezekiel watched a foreign empire, Babylon, come and destroy his home. The Jewish armies were decimated by a cruel and brutal military superpower. The people then were brought into exile. Ezekiel went with them where he served as a priest and teacher to a small expatriate community, living in exile.

Such hopelessness and insecurity can make our own situation seem so insignificant, but then again, we too are feeling a sense of dislocation, insecurity, and uncertainty, and when we come to Scripture, the Spirit of God animates these ancient words to say something to us today, something we need to hear.

It is in this context that Ezekiel has a vision of the aftermath of a battlefield, filled with corpses, dry bones, and it is a vision that is symbolic as it explains, but it names the spiritual reality that God’s people were in: a state of feeling defeated.

Yet, the spirit of God is not. God says to Ezekiel: Can these bones live? And Ezekiel replies in the most human way he can: “I don’t know. I don’t know the future. But you God do know.”

And he is given this vision: he sees the dry bones being raised up, the breath of God, the Spirit of life that animated all humanity and all living things in creation, this breath now is causing death to be reversed, a new creation.

God says of these bones that they are the house of Israel. They are God’s people who have said, “Our strength is gone, our hope feels lost. We feel cut off and separated.”

And God says to them, “I will restore you. I will bring you home. I will put my spirit in you and renew you.” God is saying this to us today, I believe.

It can feel like the church in Canada has lost a battle or just barely is scrapping by. So many of us have sent the past year stressed and anxious, our bones feel dried up, our hope feels lost.

And yet, the Spirit of God has not been defeated. God is still God, the Lord Almighty, the God of all possibilities, the God whose plans are always good, the God whose promises will not be thwarted.

Our God’s will and plan and promise is to bring salvation, forgiveness, healing, life, love, and liberation to all people – these have not been stopped for they cannot be stopped: God’s kingdom is still coming so that earth will one day be as it is in heaven.

And we know this definitely because this vision here is a prefigure of what happens to Jesus, God’s son, the messiah. For when the forces of darkness, of death and despair came against Jesus, Jesus gave himself up as a ransom to liberate us from these things, dying on a cross, a god-forsaken death. God became a cursed corpse. By this we know God is with us in our darkness moments. And in that time of hopelessness, in the time that it seems like the plan of God was truly foiled, that Jesus’ claims to being the messiah were disproven, on the third day the tomb was found empty; Jesus is risen from the grave by the Spirit.

As we celebrate where we have come today as a church, we must remember that we stand on the hope of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. We are his body as the church, and the body of Christ, while it was bruised, beaten, and crucified, the Spirit raised this body to new life.

This is our hope for a time that has seen such death. This is our hope in a time that has seen such sadness. We have the hope of Jesus.

The church is founded on this truth, and we cannot forget this. We live because Jesus is Lord.

The same Spirit that raised Jesus is the same Spirit that came on the first disciples to begin the church at Pentecost. It is the same Spirit that moved the first Baptists in Nova Scotia, prophets is like Henry Alline, to speak God’s word boldly, to live God’s gospel courageously, even in the face of all that has gone wrong in this world. It is the same Spirit that moved that is alive with us today.

As we remember God’s faithfulness to our churches in the past, and ask the question what does the future have in store? Our question sounds very similar to what God said to Ezekiel, and our answer must be the same:

O Lord God, you know. We trust you and your way. You know because you are sovereign. You know because you are good. You know because you have made promises you keep, plans that will come true.

These are words I know I needed to hear when I first started pastoring. Because the fact is many of us have convinced ourselves that we can control the future, that we can predict it and change it by our power and skill. I thought that pastoring. Looking at that depressing church growth document all those years ago in my office, I thought to myself: I can change that. I thought I could save the church.

I became obsessed over the next few years of starting programs and fundraisers and advertisements. Many of these did not have much effect (at best people from other larger churches came to these programs, used them like a free service and continued attending their own churches), and after two years of it, I just found myself burnt out and wanting to quit.

It was in that moment that I realized I don’t know what the future of this church will be. Only God knows. But what I do know is that I must be faithful to live what God is calling the church to be.

The church was located in the town of Garson. The church relocated out there in the 70’s hoping that this new suburb would be the next up and coming neighborhood. The reality was the city zoned it to be where the poor of the city were sent: supplemented income housing was built on all sides of the church. Many of the stores had graffiti on it. You would very often see police cruisers making stops.

One day a guy called and wanted a ride to church. He lived in a one room apartment around the corner from me, and as I got to know him, he faced a lot of mental health challenges. He had attended other churches that frankly saw him as a burden and ignored him. Other churches wanted to grow the church by attracting easier, and I should say, richer sheep.

This was the person God had given us, our family of faith, so we did our best, and I soon found he had a lot of friends. I put out a sign in his building that if anyone needed a ride to the foodbank on a Tuesday afternoon, I would drive them to the other end of town and have coffee with them after.

Many would ask me, “Are you just being nice to me to get me to come to your church?” And I would say emphatically: “While I strongly believe that a community of faith and weekly worship is important to our spirituality, I will always be there to help you, even if you never set foot in our church.”

I realized in those experiences that if the church is to have a future, it will be by taking up our crosses in a new way. The church must die to self: it must lay to rest its obsession with money that causes it to see the poor as worthless; it must lay to rest its expectations of what a successful Christian life is, which causes so many to feel they are not worthy to be in the family of God: the mentally ill, those who face addictions, those whose love lives are messy and complicated, those who are in the sexual minority. The church must take up its cross in a new way, embracing the discomfort the Spirit is calling us into.

It was in those moments that I know I saw the church, what it can truly me, a place where th outcasts was welcomed, a family of misfits. Let’s face it: we all are seeing very pointed reminders of the failures of the church today: racism and residential schools, stories of bigotry and abuse, or just the stories of apathy and irrelevance where churches just don’t actually care about doing what is right or sharing God’s love.

One elderly lady in my church said to me, “Pastor, I don’t know what to do with some of these people.” And I said to her, “I get it, I don’t know how to handle some of these issues either, but at the end of the day, a lot of these individuals are people without parents. I know you know how to be that.” So, the ladies of our church started cooking meals and putting them in Tupperware containers to give out. We organized community meals for people in the common area of the apartment building. It was the old folks of the congregation that said, “We know we need to be open minded, because we know what happened when we weren’t.”

It was pastoring this little church that renewed my confidence in the church: the church that is not a building, but a community of disciples, imperfect but willing to bare one another’s burdens, living like a family, being family to those that have no family.

It is amazing what can happen when the church is ready to take up its cross.

And it must be said, if we want to see the reality of resurrection, the Spirit moving and breaking in and causing new life, it will only happen, when a church is ready take up the cross, to sacrifice all that it is and even can be.

I emphasize here “can be” because so often we go out on mission for the purpose of the “future of the church,” but that really means we just want to keep what is ours. And when we do that, we will ignore those who don’t matter to our budget, our building maintenance, our membership lists. We will be vulnerable to politicians that promise power to the church. We will make the church and its mission about us.

While the future offers no guarantees – I know I constantly worried: “Will we have enough money to pay the bills? Will we have to amalgamate with another church?” – the promise of God in this passage is that God will do wonderful things, surprising things, in the valleys of dry bones.

I had a bunch of stories I wanted to tell, but here is just one: In ministering in Sudbury, I came across a young man, who also lived in the low-income housing development.

Early twenties, a poor kid, as I got to know him, he had endured the worst in this world: terrible abuse, such that just to talk with him, he was deeply erratic. It did not take long in his presence to know his soul was in deep chaos: that lethal mix of hatred and hurt.

I would come by his apartment from time to time to check on him. He was on welfare, but there was a strong possibility that it would run out, so he was looking for a job. He was about the same height as me, so I gave him some of my dress clothes. We practiced interviews. He applied around all over the place. Each time, employers would just hear how he talked, how it was hard to hold down a conversation with him and go with someone else. Didn’t matter he was willing and able. As he applied here and there, the more downcast he got.

One day, I did rounds around the apartments asking if anyone needed a ride to the food bank. I would take them as per my Tuesday noontime routine. I knocked on his door, and he answered, a bit dishevelled. I figured he was just getting up. He decided to come along to the food bank that day, even though he did not need anything.

I turned to him in the car and gave him a Jesus Calling devotional. I had gotten a bulk order of these things, figuring this was an easy way for some of the people, who were not strong readers that I ministered to, could nevertheless hear an uplifting Scripture spoken over them on a daily basis.

While the one guy went in, this young man turned to me and said, Spencer, I was sitting in my room thinking I got nothing to live for. I have no peace in my life. I was ready to end it when you knocked at the door.

I prayed with him, and I suggested, let’s see what words of encouragement the devotional he had in his hand had to offer. Turns out that day, the topic was scriptures relating to finding peace in life.

He did a stint in the hospital. After he got out I met up with him again. He seemed to be in a bad state of mind. I learned that previous to me meeting him, he had committed a crime, which he was going to be sentenced for. The possibility was weighing heavily on him. I asked him about what he believed in, whether he trusted God’s love and forgiveness in all this.

He turned to me and said that he admitted his mind is so erratic, so faulty, he resolved at some point to just stop believing anything. He figured his brain is just so unreliable, there isn’t any point to believing in anything. He told me he felt ashamed about all the ideas that would get him worked up. So, one day he just decided he would stop believing in anything.

I tried to offer some words of encouragement, but I was taken back. How do you get someone to believe in Jesus, when they don’t even think they are capable of believing anything?

I went home that day particularly distraught. I remember praying, “God how can a person like that be reached? How could a person like that be discipled? God you’ve got to reach this person, but if the Gospel means anything, it has to mean something to a person like that. The Gospel is good news to everyone, especially a desperate, troubled young man, who needs hope in his life.”

My prayers for the next little while took on a tone of frustration and disappointment.

A little while later, I came by his apartment. I found him in the apartment’s communal kitchen. He turned to me. “Spencer, I was sitting in my apartment. I was ready to end it all. I just felt so worthless. But then he showed up.”

“Who showed up?” I asked. He just pointed upward. In that dark moment, he heard a distinct voice say to him, “Your life is worth something to me.”

“Spencer, I don’t know what I am, but I know I ain’t an atheist anymore.”

God surprised me that day. God surprises us most often when we are ready to be the Gospel for the broken and when we are willing to be broken for the Gospel.

It is a beautiful irony that church growth did not happen when I obsessed about growing the church. The church started growing when we resolved to be there for those in need in our communities even if it could cost us “the church” as we know it.

The church will only find itself when it is ready to die to self. It will only rise when it is willing to dwell in the valleys of dry bones.

As we celebrate today, Brookfield Baptist Church, where we have come from, where we are now, where we hope to go. Remember we are the body of Christ: We live in this world crucified and only in and through this, we can see moments of resurrection.

Let’s pray:

God of hope and new life, we praise you that you are faithful. You have been faithful through the years in this church, and so we trust you with our present and future.

Lord, we do not know what the future holds. And we have seen so much discouragement these days.

Lord, teach us in new ways to trust your Spirit. Inspire us in new ways to take up your cross.

Empty us into this world, so that we can be with those who need to hear about you.

Permit us to see moments of resurrection, moments of your kingdom come.

We pray longing for the salvation of all people, the restoration of all things.

These things we pray in your name. Amen.