Tagged: theology

The Faith We Do Not See

Preached at Third Horton (Canaan) Baptist Church, Sunday, July 16, 2023

He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt: “Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’ But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven but was beating his breast and saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other, for all who exalt themselves, will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted.”

Luke 18:9-14, NRSV

As I said before, I was pastor of First Baptist Church of Sudbury for five years before coming here to Nova Scotia.

One time, I remember doing a house call, and the person who attended my church had a friend there. This friend asked for my card and messaged me about going for coffee.

When we met for coffee, this person confessed to me her struggles with drug addiction, and while I said she needed to seek out addiction counselling, we decided we would go through a book called Addiction and Grace by Gerald May, which is a really powerful book.

So, this became a weekly thing, us meeting and discussing some bible verses, a chapter of this book, and praying, and this really became something I looked forward to. This is why I became a pastor: my love of encouraging folks to grow deeper in their faith in God, to instill some good teachings about the meaning of grace, and to see how that affects a person’s life. I had something she needed.

I remember one morning getting up, hustling to get my kids out the door to the bus, get my breakfast, and shower to make it to coffee with this person. I made it on time despite the coffee shop being on the other side of the city. I remember asking her in our conversations, “What does faith in God mean for your day-to-day life?” I was expecting the usual vague answers I got from folks. She responded by saying, “I don’t know if I really have faith. I don’t know whether or not I am a Christian. I can’t remember the last time I went to church. I have done so many terrible things. One pastor told me that if I really had faith, I wouldn’t do those things. All I know is that every day, I wake up feeling so lost. I pray God be merciful to me today, and all I know is that if I don’t do that, I just can’t get out of bed.”

It struck me that I had gotten up and rushed out the door that day without much thought about God at all. Ironically, I did this in my pursuit to come and help this woman to have more faith.

The thought struck me that maybe this woman, in her own way, knows something about faith that I could learn a thing or two from.

I was so eager to think I was the faithful one (pastor man) here to improve her faith (an addict that really did not, by most outward appearances, live her faith) that I failed to realize that perhaps God sees something different.

As I said last week, I teach theology. And so, if you ever took a theology class with me, you would investigate things like what the Bible says about certain topics, how Christians have thought about things through the ages, and what that means for our times today. Over the centuries, there are those classic statements Christians have been convinced are true that form the core of our faith, one of which we explored last week: We believe God is one being, three persons: Father, Son, and Spirit, all equally and fully God, which speaks deeply of how God’s essence is love itself. Others include the statements that show up in the creeds like the Apostles Creed or Nicene Creed. These sorts of statements Christians have, throughout the centuries, come to regard as orthodox, meaning “right belief.” If we did not have these, our Christian faith could be compromised.

And so, one of the jobs of theology is really to reflect as best we can on what is true and good, what they mean, so that we can believe truly and act well.

Now, in its own right, this is something all Christians, indeed really any human being, are tasked with doing. We ought to believe what is true over what is false. We ought to do what is right as best we can over what is wrong. When it comes to our faith, it is obviously better to have a good understanding of what the Bible says and what the faith teaches if we want to follow it effectively. Such things are virtuous.

But there is a kind of problem that pops up throughout the Bible that cautions us when we undertake this activity, a kind of Achilleas heel to the whole endeavour. We all must seek to do what is right, but does God love us only when we do what is right? Are outward actions always an indication of what is going on inside?

We all know the answer to this, but we often don’t practice it to its fullest extent. We, Protestants, tend not to believe that we are saved by works, but we are quick to use beliefs to do the same thing. Many of us use theological tests to prove we are good. One writer suggested that we often believe in salvation by mental works, theological righteousness. You see, we must believe what is true, but does that mean God only loves us because we have these ideas in our heads?

And so, we are left with this kind of conundrum. We strive to think what is true and do what is right, and in so doing, we use categories like good and bad, true and false, and we might even use terms like orthodox and heretical (“heresy” means “error” by the way), or just Christian versus non-Christian. But scripture warns that when we use these categories (and use them, we must) there is always a tendency for the human heart to distort them into ways of presuming this is why I know I have an authentic relationship with God and you do not; or that my faith counts and yours does not; or why I belong in the church and you do not.

There is a big difference between believing in the right things and believing in the right way. Both are important, but one is a lot harder to see.

This causes a lot of problems for folks like me as a professor because I can evaluate beliefs, whether in an exam or an essay, how well someone thinks about something, but I can’t see why people think it or, more importantly, how they hold these convictions in their heart. You can test words on a page quite easily. The heart is a bit more tricky.

Yet, it is there that faith really resides. This is something only God can see, and we so often miss. We often only get little glimmers of what is going on in a person’s heart when all the layers of performance and presumption are pulled back. And these moments are really when the reality of the kingdom of God shines through the clouds of human religion most powerfully.

It is this fact that Jesus tries to instill in this parable. You see, throughout the Gospel of Luke, Jesus has been teaching folks about what the kingdom of God means, what it looks like when God has his way in our world, and, more surprisingly, who belongs in God’s kingdom.

God’s kingdom is, says Luke’s opening chapters, for a poor, young Jewish girl whose fiancé discovers she was pregnant before they were married, but she is, in fact, the mother of the Messiah.

God’s kingdom is for some rough around the edges fishermen, folks from the wrong side of the tracks in Galilee, yet these are the people Jesus makes into apostles.

God’s kingdom is for the sick and the suffering, the poor and the hungry, and against the proud and the powerful: the people that seem to have their faith well put-together.

In this kingdom where the lowly are raised up, where the first are last, and the last are first, I am constantly bewildered at who Jesus sees as having faith.

Jesus sees the trust of a centurion, a military commander of the legions that are oppressing God’s people (the man literally had idolatrous images on his breastplate and shield) – Jesus sees this person as having profound faith.

Jesus sees a sinful woman who comes to him when he is surrounded by religious folk, a woman who pours wastefully-expansive perfume on him and weeps, and without her even saying anything, Jesus says she has saving faith.

Jesus uses the example of a Samaritan man, a person who was regarded as a heretic by the Jews, over a priest and a Levite, as an example of someone who really knows what eternal life is about.

Here, it says Jesus tells them this parable because “some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt.” Jesus tells the parable of a Pharisee, a religious expert, you might say, coming into the temple and praying, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’

While the Bible does say to do pious things like give of one’s money and fast and pray, and obviously condemns stealing and things like that, it is how he does it that is the problem. Notice that he thanks God for all the things he does, not what God does. And when it comes down to it, his faith rests on comparisons to others, how he is superior. As I said, there is a big difference between the right belief and believing in the right way.

Do we ever do that? Perhaps we have more subtle ways of saying it: “Thank God I was never exposed to those kinds of things. Thank God I wasn’t raised like that. Thank God my life did not turn out like that.”

Thank God I am not like those others. Who are “those others” for you?

Is it our coworkers, friends, or family members who just refuse to take God seriously and come to church? Unlike us! Is it those lukewarm Christians that don’t take their faith seriously? Unlike us! Is it those liberal Christians who have allowed the culture to infect their faith? Unlike us! Is it those fundamentalists who just refuse to open their minds and educate themselves? Unlike us!

Whoever it is, we know we are saved, we have an authentic relationship with God, and they do not because we believe these things and we do these things, unlike them.

Jesus sees it differently, and he tells us about a tax collector: tax collectors in those days were people that the Roman Empire recruited to intimidate and extort money from their own communities to help fund their own oppression. They were traitors and thugs who got rich off of extortion. To put it plainly, there is simply no way a member of God’s people could do those kinds of things.

What does this person do? “Standing far off,” it says, “he would not even lift up his eyes to heaven but was beating his chest and saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’”

Mercy for a tax collector? Some might call that cheap grace. I knew one pastor who would call grace without changing one’s ways “loosey-goosey, lovey-dovey grace” (a good theological phrase if there ever was one).

And yet, Jesus says, “I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other, for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted.” Jesus uses a really important term here: justified. Paul uses the same language to say that Gentiles can be members of God’s people by trusting what the Spirit has done, despite not being entirely obedient to all of the laws of the Old Testament.

Paul says we are justified by faith. Luke records a tax collector being justified by humility.

If you were to ask me whether that was enough, enough to be a church member or something like that, I would struggle to say that this is enough to go on. What the tax collector says is hardly a doctrinal statement. It falls short of the other statements about what is required for salvation in other passages. But this tax collector is one of those people like the centurion or the woman who anoints Jesus’ feet or the good Samaritan that really are outsiders to the community, on the margins of religion, people that we might be tempted to say they don’t make the cut of what faith looks like, and yet God sees something different.

Who is that for you? Who do we exclude that God might include?

One time, I was asked to speak at another church for a conference in Sudbury. The theme of the conference was “Living in Exile,” and it explored how we live in a secularized culture. Pastors from the evangelical ministerial came, but also a number of catholic priests. I remember one pastor seeing the priests show up in their collars, come up to me, and say, “Interesting that Catholics would come to this. Perhaps we can witness to them what the Bible says.”

I remember at the beginning of my talk, I had a number of Bible verses I wanted to talk about, and for fun, I said, “Hey, let’s do an old-fashioned Bible drill.” Have you all done one of these? You hold your Bible up, the leader calls out a passage, and you try to find it before anyone else. Well, guess who won those Bible drills? Father Jim beat all the Protestant pastors in the room. Badly. I remember on another occasion, one pastor admitted to me, sheepishly, “I don’t think Catholics are Christians, but I think Father Jim is born again.”

It is funny how we can have our paradigms turned upside down with little experiences like that. Again, who is it for you? How have we seen and made a judgment that might not be how God sees things?

There is an old parable that goes like this:

In heaven, one day, the angel Gabriel was given a gift to deliver to whomever he chose. The person who received this gift would know that fully that God was with them. Gabriel dutifully went out into all the land to find one deserving of such a precious gift. He looked at all the kings and tried to find the one that upheld justice like no other. He looked at all the priests and monks to find one whose piety was beyond the rest, and yet, each came up short. Frustrated, he returned to heaven and cried out to God’s Spirit, “Lead me to the one you choose as deserving!” and so the wind of God blew Gabriel far, far away into a distant land, and the wind of God led him to a house where he found a man weeping bitterly in prayer to an idol. Gabriel was indignant, “God, there must have been some mistake!” The parable ends with the voice of God answering, “O, Gabriel, do you not know that I see the human heart? And O, Gabriel, after all this time, have you still not seen what my heart is like?”

I remember coming across that parable and being deeply moved by it. I looked down the page to see who wrote it. I was surprised to find that it was not a Christian parable. It is actually a Muslim one. It is a well-known parable in Sufi Islam.

When I was a chaplain at Thorneloe University, I made a point of getting to know the other chaplains, one of whom was a Muslim chaplain. He drove a taxi as his day job, but he volunteered his time to encourage the students at the university. He was someone that always had a beaming smile.

I remember having coffee with him, and before I did that, I went over in my head various ways I might give a reason why Christianity is true and Islam is not. I remember being a bit braggy in our conversation, describing all the good things I did in my ministry (you know, to be a good witness). He nodded along. In the course of the conversation, I remember asking him, What does your religion mean to you? He replied, “Spencer, I wake up in the morning with joy in my heart because God is merciful to me, even though I don’t deserve it. I try to trust this every day, and so, I try my best to show that grace to everyone around me.” I remember stopping and pausing, a bit stunned. I was not expecting that answer.

One theologian once said that the kingdom of God is like an uncle who gives you a coin. Every time you think you have God in the palm of your hand, the Spirit reserves the right to pull off a magic trick and surprise you.

I think Jesus taught me a thing or two that day about what sharing the Gospel means or, better yet, what it doesn’t. My prayer was and very much still is that all will know Jesus as their lord and saviour, but I have also learned the hard way that how God is working around me is not always the way I assume it to be.

Sometimes, when I think I am the one God is using to show other people grace, I end up realizing God is using someone else to teach me a thing or two about grace.

While experiences like that can disrupt us, perhaps confuse us, but hopefully humble us, I find myself deeply comforted by the fact that daily, I am surprised by how much more gracious God is. But with that comes the realization that so often I have missed this because I have treated God’s grace as limited.

It reminds me that at the centre of our faith is the story of how when Jesus came preaching the kingdom of God, turning people’s expectations about God upside down, and God’s own people, the leaders of biblical religion, and even Jesus’ own disciples refused to see it, and while we might be quick to shake our heads at those disciples, we are so often no different.

Jesus was betrayed and crucified, treated as a blasphemer and a rebel, executed on a cross, dying as one, as Paul says, “under the curse of the law,” dying outside the bounds of religion.

We know mercy because Jesus bore our sins.

We are saved because Jesus counted himself forsaken.

We are included because Jesus was excluded.

Despite all the ways we can take our faith and still make it about us, about how we are better, about how we are safe, about how we are deserving, and others don’t measure up, God does not give up on us. God sees our hearts, all that we are, and all that we have done, and in this, God chooses to love us with his very body and blood. God says his kingdom is for you.

The question is whether we will daily choose to see it.

Listening to Listen: Abortion and Becoming “Pro-Voice”

Happy Belated Canada Day, everyone. When I originally signed up to speak with you a few weeks back, my obvious thought for a sermon was to speak on faith and our nation, seeing that it was right after Canada Day. I had that sermon ready to go.

But the events of this week south of the border have been on my heart and mind. It is an oddly Canadian thing to feel connected to the controversies in the United States. Some days Canadians follow politics in the States closer than our own, perhaps because our politics are just so much more respectful, we feel bored listening to it.

The United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and that has us Canadians talking about it, even though it does not directly affect us. It has been all over CBC Radio, which I listen to on the way to work. For many of us, we feel connected to these events. Many of us have American family members. Many of my friends are American Baptist pastors. Many of us wonder whether something like this could happen here. Others of us hear the toxic rhetoric from our own circles.

Over social media, I have seen a disturbing mix of gloating on the part of conservatives and rage on the part of liberals, finger-pointing memes that attempt cute but all too simplistic “gotcha moments” like it is all one big game.

For conservatives, the gloating justifies why they supported Donald Trump, finally coming to fruition. Supporting an immoral man so that republicans could control the Supreme Court was worth it. For others, this marks a terrible victory for bigotry that is taking over the public discourse, where people have climbed into places of power using lies and demagoguery, pushing the United States closer to something like Margaret Atwood’s dystopia, Gilead.

For us, north of the border, I am very thankful that we have a completely independent judiciary, can I just say. I also feel like we are watching our neighbours, our closest ally in the world, pull themselves apart. The rage is palpable as the protests by both sides edge closer and closer to violence. I wonder if the US is on a collision course for another civil war.

And so, I told the organizers of the service this week that I would speak on the topic of abortion today. But let’s be clear about something up front:

This is not a liberal versus conservative issue.

This is a scriptural discernment issue.

This is a truth and compassion issue.

This is an issue that involves people.

When the world wants to shout, I think that is a good indication for us, Christians, that we need to stop and listen, but not to the shouting. We need to listen to the whispers of God’s voice in Scripture; we need to listen to the advice of our Baptist forebearers, but also, we need to listen to each other, especially to the cries of the lives affected, the voices of women.

So, I have entitled this sermon “Learning to Listen: Abortion and Becoming ‘Pro-Voice.’” The term Pro-Voice is based on an excellent book by Aspen Baker that I will reference later.

1. Listening to Scripture

So, first, can we listen to what God might have to tell us in Scripture? I say that knowing that this is a debate where people love citing the Bible as if it is obvious and clear on the matter. However, let me survey some of the Scriptures people cite in these debates, and let me suggest that perhaps the voice of God might not be saying what people try to make it say.

This is a topic that cannot be discussed by just one Scripture. As I thought about it, there is really no other way to handle this than by going through a couple¾there are about half a dozen of them–that people bring up (there are others, but these are the most pertinent ones). So, that is what we are going to do.

Now, there are several scriptures that don’t say much at all about this issue that constantly get quoted. So, let’s start with those:

A. Psalm 139

For instance, Psalm 139:13 says, “For it was you who formed my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb.” There are similar ones in the books of Job and Jeremiah. I saw this on a billboard driving through the South one time, but it really has nothing to say about the legal status of a fetus. Technically, God knits all life together. So, already, one of the most commonly cited passages in this debate says actually very little.

B. Luke 1

There are other Scriptures that are not as convincing but have some weight to them. One of these is how in the Gospel of Luke, chapter 1, Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist, sees Mary, who is pregnant with Jesus, and it says that the “child leapt in her womb and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit.” You see this one often around Christmas time. Some have taken this to imply that, obviously then, all fetuses are children. Well, I don’t think that is really Luke’s point in this passage, but be that as it may, we also don’t know how far along Elizabeth was. To feel a baby leaping is something that would happen well into the second trimester, so if this text does speak to this issue, it does not seem to say anything about the condition of the unborn in the first trimester. In Canada, 90% of abortions happen in the first trimester before movements can be felt. So, this text doesn’t say enough.

C. Genesis 1

A much more important text in this debate is Genesis chapter one, verse 27: “So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.”

This term “image” is used later in the book of Genesis to speak about how Adam’s son, Seth, is like him in his image. It is a parental term. If you were to look at my sons, you might say they are chips off the old block. They look like me. They are in my image. Genesis 1 is saying that all humans are God’s children; God sees himself in them and them in him. Genesis 1 teaches that human life has inherent dignity and worth in God’s eyes, no matter the gender, the health, the mental ability, which should say something when we are placed in a position to decide what kind of human life is worth living.

However, as important as this passage is, this passage does not tell us when a human person, in the legal sense, begins. It tells us the worth of human life, but not its origin. So, it is important, but it is only one piece of the puzzle.

D. Exodus 21

The only passage in the Bible that deals with the destruction of a fetus is Exodus, chapter 21. It reads as follows:

22 “When people who are fighting injure a pregnant woman so that there is a miscarriage and yet no further harm follows, the one responsible shall be fined what the woman’s husband demands, paying as much as the judges determine. 23 If any harm follows, then you shall give life for life, 24 eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25 burn for burn, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.

The laws of the Old Testament are made up of different types. You have some, like the ten commandments, that are direct: Do not commit adultery, do not lie, etc. Others, like this one, is a case law that work as applications: if this happens, you should do that.

This situation is a fight where a pregnant woman is struck, and a miscarriage happens, and if the woman is harmed permanently, the offender is harmed in retribution. It is not the case when a woman seeks an abortion. For in the Hebrew mindset, birth control of any kind was just not on their radar because the ideal was to have as many children as you could.

This is the only case where the destruction of a fetus occurs, and according to this passage, a fine is paid. It is paid to the husband because he, in that culture, was considered the patriarch and lord over his wife, who has his property. So, one quickly feels that this is a text written for its own time and place.

Nevertheless, the most important detail of this text is that a fine is paid. According to Old Testament laws, if you murdered a person, you got the death penalty, life for a life. The implication here is that if a miscarriage happens, and we are not told anything about how far along the pregnant woman is, the offender pays a fine. Thus, it implies a legal person has not been killed.

Some more conservative commentators have tried to argue that this is merely referring to a premature birth, that the word for miscarriage could mean something else, but that is not how it was understood in its own time or in later Rabbinical and Christian commentaries.

However, some later Jewish commentators argue that this case only refers to when it happens to a woman in the first half of her pregnancy, before the fetus is formed sufficiently. In the second half, it could be considered murder.

And so, some have argued that just as Scripture pushes God’s people toward equality between men and women as the biblical narrative progresses, so also does Christian tradition become more sensitive with regard to the unborn.

But the question remains, when does a fetus become a person? When does it become a legal person? When should the government protect what it can discern to be human life?

Some have argued, based on this passage, that a person is a person when they take their first breath after birth. When the first human in the Bible, Adam, was made a living soul, this occurs in Genesis 2 when God breathed into him the breath of life. With the first breath after birth, the human person is identifiable. This was the view of Palestinian Jews in ancient times, and in modern times, this argument was made by the Baptist ethicist Paul Simmons.

However, is breath the real mark of life with dignity? After all, there are lots of creatures out there that are alive but don’t have lungs and acquire oxygen in other ways, and we believe in animal rights. A fetus gets oxygen through the blood in the umbilical cord. Does that count?

If the first breath is the mark of personhood, can a pregnant woman have an abortion right up until labour starts? Late-term abortions are very rare, and in Canada, they are really only done when the life of the mother is at stake. In Canada, abortions after the 21st week of pregnancy account for 0.59% of all abortions.

On the other side of the spectrum is the view that a human person begins at conception. This is probably the one we are most familiar with, often called “life at conception,” but that is a misnomer in the debate. No one is debating whether life begins at conception. In fact, the sperm and ovum are also alive before conception. The question is rather does a fertilized zygote, a set of multiplying cells, which does not have thought, a nervous system, or a heart, so small it could fit on the end of a pin, growing to about the size of a lentil as an embryo–should this be considered a legal person? Baptist ethicists like David Gushee and the late Glenn Stassen hold that the sanctity of human life compels them to refuse abortion even at this early stage.

Early Christian writers like Clement and others support a similar view. They held this view because they assumed the philosophy of Plato. What does that mean? Plato believed that humans have souls in the sense that what made the person truly a person was not based on their bodies or brains but was based on an eternal substance of the mind that could be divorced from the body and brain. That is a bit different from the earlier Jewish belief in the soul that would say that while we have a spiritual dimension to ourselves, it is always in connection to our bodies. One writer put it that we don’t so much have a soul. We are a soul, a holistic unity of spirit and flesh. We are enspirited bodies.

So, several early Christian writers adopted this more Platonic notion that separates mind and body, soul and flesh, and by this, a zygote from the beginning of conception has a full soul, the same as a fully developed human. And this position became Catholic dogma and, by extension, the default setting of most of Christianity, including the modern pro-life movement.

Now, as I said, the early church and Judaism had two wings in the spectrum of their views: one was personhood beginning at first breath, the other, beginning at conception. However, there was a diversity in the early church and Judaism.

The most common view was a middle-ground view. Thinkers like the Alexandrian Jewish writers but also important Christian writers like Tertullian, Origen and Augustine (if you don’t recognize these names, let’s just say they are heavy hitters in theology). They believed that a fetus was a person somewhere in the second trimester, corresponding to the degree of the formation of the fetus.

Now, we know today that a fetus’s heart is discernable at six weeks. But does a heartbeat define a human person?

We know that somewhere around the 12th week, the fetus has a formed nervous system and thus, probably can feel pain. Does the ability to feel pain indicate to us that this is a life we need to protect? 80% of abortions in Canada occur before the 12th week.

We know that the fetus becomes viable around the 24th week, which means if it was born then, it’s probable that it would live. Is this the point where the government has the prerogative to say an abortion should not take place unless the life of the mother is at risk? As I said before, late-term abortions are very rare in Canada.

2. Listening to Our Baptist Principles

As you can see, this topic is one that leads to more and more questions. What do we do with that? I have learned that the principles of our Baptist tradition were devised in many ways to aid the believer in walking these difficult paths, where the road ahead comes to a blind crest. So, what might our Baptist principles tell us?

While I don’t think Baptists are automatically the “best” Christians, much less the “only” Christians, I do think our Baptist principles can be virtuous practices that can help us navigate this complex post-Christian, post-modern world we live in.

A. Humans have Rights and Freedoms

One principle that all Christians share is that we believe that because we are all made in God’s image, all human life has dignity and has been bestowed rights and freedoms. Baptists have particularly emphasized rights and freedoms.

Now, someone might pipe up and say then what about the rights of the unborn? Here is a tension between the rights of the pregnant woman and potentially the rights of the unborn.

B. Separation of Church and State

In this case, I believe it is important to keep in mind the second Baptist principle: separation of church and state.

That is to say that if we believe that life begins at conception, and by that a full person because a full soul is imparted at conception if this is a premise based on the beliefs of Christianity, a particular belief about the soul, my Baptist faith cautions me from imposing this view on others who might not share it.

Again, someone might say that imposing this view is necessary when human life is in danger. Many would insist that a fertilized zygote is a potential human being, and by the sanctity of human life in any form, it ought to be protected.

But this conversation must admit that what it means to be a person and when a person begins legally is not clear, both in public discourse and in Jewish and Christian theology. As we have been asking: Is it at conception? An established heartbeat? The development of a nervous system? Fetal viability? Or at first breath after birth? Arguments can and have been made for all of these with no clear winner.

If we cannot prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that one option is the obvious standout, we ought not to be insisting that the government enforce one view, particularly not the earlier ones that impose so much on a woman against her will.

C. Liberty of Conscience

In this case, another Baptist principle is important to keep in mind: we believe in the liberty of all people to decide matters based on their conscience.

Now, this is not an absolute liberty. This does not mean we ought to be free to do anything we want. I did not have the right, as we have seen in the pandemic, to jeopardize the health of my neighbours or co-workers or people I interact with in public spaces but refuse to wear a mask or show vaccination information. Governments and organizations do have the right to regulate spaces based on health and safety.

And if the nature of the unborn was obvious, as some think it is, I can see a better case to say why it ought not to be left up to choice.

While it is not a person’s decision that makes a fetus into a person, it is up to people to recognize another person, and the question is, who has this power? Who has the right to pronounce when a zygote, an embryo, or a fetus becomes a person when the matters are not clear?

If these matters are not obvious, it is appropriate then that the power of this decision lay neither in the hands of the state nor the church nor the biological father, who simply does not have the same bodily risk in the matter, but rather the power of this decision should reside in the hands of the person who will be most affected by that decision, namely the pregnant woman herself.

This does not mean that we have to view a decision always as the right decision. There are lots of bad reasons to have an abortion, but at the end of the day, the responsibility falls on the woman herself to make this difficult choice.

3. Listening to Each Other, especially Women

If we can understand these things, this issue takes on a different character. It is quite possible for Christians to occupy a muddy middle ground that sees abortions as a tragedy but is not interested in imposing our convictions on another person using the laws of our nation.

We can ¾in fact, we must¾resist the either-or of our polarized culture and its toxic, corrosive effects on honesty, decency, and thoughtfulness. We can be profoundly and fervently committed to the dignity of all human life but admit that there is a right way and a wrong way to go about that.

A. Accepting the Diversity of Voices

In the midst of a world that is divided and diverse and even a church that is as well, I know people who take their views and live them out graciously. I know people who are pro-life that have chosen to adopt the babies of unwanted pregnancies. On the other end of the spectrum, I know Christian social workers who are pro-choose that have worked at deep personal expense to help women out of abuse and poverty through education and empowerment. I think the church would be impoverished if we refused to see the good character of either of these people.

I think of the conviction of former US president and evangelical Baptist Jimmy Carter. He writes in his important book, Our Endangered Values, that during his presidency, he believed that the Bible taught the sanctity of all life, so he was and still is, personally, against abortion. However, he also believed in the separation of church and state. He believed it was the right of a nation to choose its values democratically. So, instead, he funded programs to help young women and mothers–things like sex education, birth control, free contraception, testing, funded daycares programs, work programs, etc.–so that if a woman truly wanted to keep her baby, she could feel supported. The result was that abortions were lower doing his presidency than during the two Republican pro-life/anti-abortion presidents that came before him and him after.

The right way to go about this issue involves giving people the space to work out for themselves what quite possibly could be the most difficult, life-altering, haunting decision a woman could make in her life.

The right way is to listen to and support people medically, financially, and emotionally–people who are vulnerable and scared and only then do people feel empowered to make an informed decision because they know they are not alone.

B. Listening and Walking with Women

Aspen Baker formed an organization that is devoted to doing just that. Her philosophy, the title of this sermon, is called “pro-voice.” Look up her Ted Talk on this subject. Her organization is a helpline devoted to listening to the needs of women who have had abortions. She believes that one of the most important things we can do in this debate is to listen to the experiences and needs of women without judgment.

And this does not mean all women will think the same way. What she found was that there were many on the pro-choice side that valorized abortion as liberating. Feminists that when they got pregnant, just could not bring themselves to have an abortion or when they did have one, they found themselves experiencing regret, guilt, and anguish.

On the other side, she handled calls by women, fathers, husbands, and pastors who were adamantly pro-life before, but because of certain complicated circumstances, they ended up considering that abortion might be the necessary path, and they felt deeply unprepared to consider these things.

Aspen Baker, in her book, speaks about navigating life in the areas that are gray, where the questions do not lead to clear and definite answers. The question we have been asking (although there are many other questions in this debate) is when does the fetus become a human person, a person in the legally definable sense? How do we live this out? And when we have surveyed the most pertinent Scriptures, we come up short of complete answers.

Now, I am sure you all want me to solve this issue for you. I could tell you where I feel most comfortable drawing that line. But I am a man that has never experienced anything a pregnant woman might face. It is not my decision, nor is it an obvious decision. Let me just tell you that some issues are not easily solved. In fact, they shouldn’t.

Can I tell you I have so badly wanted these questions to have an easy answer? When I was in my first year of Bible college, I had a friend that knew me as a Christian and as a Christian that always had an answer for things. She came to me quite troubled. She was pregnant. She was pregnant with twins. However, one twin died and became what is called a molar pregnancy, essentially becoming something like a tumour that kept growing. Doctors said it should be removed as it could cause serious health risks (infertility, even cancer, later on), but to do this, the other baby–that is the term she used¾had to be aborted and removed.

What would you do if that were you? What would you say to her if you were me? If you can believe it, in Bible College, I was a member of the pro-life club, and my answer as the plucky and ultra-pious, know-it-all Bible college student was: “Don’t do it. Abortion is wrong. Pray and have faith.”

This woman–fortunately–did not listen to me. She went ahead with the procedure, and because of it, she is healthy today and has gone on to have a family.

That experience impressed me that life and faith might be more complicated than I want them to be. Anyone who says the solution is obviously this or that is usually someone who has not really come to grips with the complexities of life and the intricacies of the Bible. Life and morality are not always an obvious thing.

It can be frighting thinking about just how messy and grey the world can be.

It can feel scary not knowing what to think, especially if you believe that your salvation depends on believing and doing the right things.

This can cause many of us to retreat into easy answers, black and white thinking that permits neither questions nor alternatives.

But it is here in reality, in this messy thing called life, that our humanity is found.

And it is here that God’s grace finds us: not despite our humanity but in it.

C. The Character of Grace

If we can realize this, we must know that to become a mature follower of Christ in this complicated world involves moving from partisan politics and obsessing over having the right position or policy (although these have their place) to simply dwelling with people, hearing their stories, and being a gracious presence there in their midst.

I have learned the difficult lesson as a theologian, who has devoted my life to reading Scripture and the great works of theology, all to strive to synthesize the best answers on doctrinal topics in our pursuit of truth (which I believe is a pursuit we all must do). I have learned that some issues don’t have clear answers–that’s the truth–and sometimes in life, the point of things is not having the answer, but meeting these difficult situations with a certain character, that difficult balance of honesty and empathy, conviction and compassion, and that this is the only way to live with a clear conscience in this corrupted world.

If this is the case, we might listen and hear the voice of God from Scripture say something else beyond the Scriptures we just surveyed. In all the ambiguity of life, the Word of God might simply be saying something like this:

“Let everyone,” says the Apostle James, “be quick to listen, slow to speak, slow to become angry” (James 1:19).

Or it might be what Paul simply advises, that in all the fragmentation and division in this world, he simply says, “Be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ has forgiven you.” (Eph. 4:32)

Or it might be what the Prophet Micah said, “What does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8). When life gets complex, sometimes the only thing we can do is be fair and forgiving and admit that in all of life’s moments, whether moments of success or failure, joy or tragedy, we need God. We need the grace revealed in Jesus Christ. We need the one who has said, “I will never leave you or forsake you” (Deut. 31:6).

No matter what our views on anything, all we can do, all we must do, from beginning to end, is to trust that.

The Shack (Part Three): The Scandal of Evangelical Orthodoxy

So, if you have been tracking with this review, I began by summarizing the story of The Shack and remarking how I simply do not see a lot that people should be upset about. It is robustly trinitarian, Christ-oriented, a free-will theology with forgiveness at the centre. It is a narrative written by a man who obviously does love Jesus, and has an amazing testimony of working to understand that through pain and suffering and brokenness.

In my second part, I noted that The Shack has gotten a lot of bad criticism. I think a lot of this comes from a mentality similar to the fundamentalist one I had, so I offered bits of autobiographical information where I noted the irony that much of what I thought was “conservative” in my more narrow tradition of upbringing, ironically, when I started reading broader in the tradition, was found to be unorthodox. Here we will explore some of the objections to The Shack to point that out.

Here we go… Allow me to put on my theologian hat, since technical objections warrant technical responses.

God as a mother: God appears as a woman named Papa. Some people lost their minds about this. However, the Bible does use motherly imagery, which I argue at length here. And it is important to note that if a mother’s love and femininity are good, they can and should be used to communicate God’s love and goodness. The same God is a shepherd, a warrior, a rock, and a fire. To refuse to use these metaphors undermines the goodness of women and replaces God’s love with patriarchy. Notably, there have been accepted teachers of the church, like St. Julian of Norwich, a gifted mystic, who records theological vision of God as mother in her Revelations of Divine Love. In The Shack, God appears as a woman, but that is because God appears to Mack, who had an abusive father, with the love that he already understood. By the end of the book, after Mack forgives his father, Papa appears as a father as well.

Non-hierarchical nature of the trinity: Some got upset at the idea that the trinity in The Shack is submissive to each other, Father to Son, Son to Spirit, etc. While Scripture does have the Father directing the Son, who in turn responds obediently, that is just one contour. Jesus is the Word of the Father, such that when you look at Jesus, you see the Father. Their identities converge. The Son has no authority but the Father’s, but the Father has no Word but the Son. John 17, one of the most clear passages of trinitarian relations in the New Testament, has Jesus saying that the Father is in him and he is in the Father. They glorify each other. It is reciprocal and reflexive, not one-sided. It is language of mutual possession similar to Song of Songs, “I am my beloved and he is mine,” or the mutual ownership of 1 Cor. 7:4. St. John of Damascus noted that the persons of the trinity are not individuals, but are persons through each other, thus an inherent mutually and equality is implied. Augustine and Athanasius both insisted what the one member of the trinity has and does, they all do together. This is enshrined in the Athanasian Creed. To depict mutual submission in the trinity, I think, is getting at the unity and mutuality of the trinity that the greatest trinitarian thinkers have affirmed.

Constructing a hierarchy between Father and Son is quite dangerous. It is often used to legitimate hierarchy between men and women, which is easily abused. Often, those that support this hierarchy also deny that there are women leaders in the Bible. It is very problematic when it comes to the cross as we will see, but it falls into a kind of sub-ordinationism. If God is God because he is sovereign and has authority, if you define God that way, then the Father has sovereignty and authority over the Son, effectively making him more “God” than the Son, which is why St. Athanasius resisted that so heavily. Does not the submission of Christ in his love, the tenderness of Christ on the cross show God as well? There is nothing the Father has that the Son does not. This also makes the death of Jesus, his weakness of the cross, a scandal to God. That is obviously a problem…

Not penal substitutionary atonement?: As I said, the unity of God in the trinity is very important. It is especially so for the view of the cross. Young wisely depicted the Father as having the marks of the nails. He is reminding us, perhaps unwittingly, of Augustine’s dictum: what one member does, they do together. Obviously not all of God died, or else there would be no resurrection, but the cross was a trinitarian act. The cross shows the entire character of God. If Jesus is the visible image of the invisible God, there is no God that can be known apart from the cross. Father, Spirit, and Son are cruciform love.

Young seems critical of what is called penal substitutionary atonement (PSA). Now, all Christians hold that the death of Jesus saves us from our sins, but there are many particular theories about how this happens. PSA is complex parsing of the atonement that emerged in the theology of the reformers like John Calvin. At its most basic, it holds that God had to kill a substitute, namely Jesus, in order to atone for sin. It is largely absent in the early church because they used other readings, notably a kind of ransom view. So, historically, there is more than one way to read the work of the cross.

Personally, I resist using language of PSA, not because there aren’t any passages that suggest aspects of it (like Gal. 3:13), but because the cross is understood by several metaphors and strands of logic, each valid: obedience, military , sacrifice, priestly, legal, ransom, economic, kinsman redeemer, etc. They are distinct but overlap, and offering one grand theory often sloppily forces the proverbial circle into the square hole. There is substitution imagery and sacrifice imagery that has nothing to do with punishment. In the OT, it is not commonly understood that the animal sacrifice (or grain for that matter!) is being punished in the person’s stead. If Genesis 22 has anything to say, it speaks more about God already in his mercy providing than God in his wrath needing something to punish. The sacrifice was not for God, but for human conscience (Heb. 9), cleansing guilt. Shedding of blood has everything to do with sealing an new covenant and cleansing, not necessarily punishing something. In Mark 2, Jesus is able to forgive sin by mere pronouncement, no sacrifice necessary, so the logic of crucifixion rests elsewhere.

I find there are a number of scriptural themes that PSA does not incorporate well. No one ever talks about how Jesus lifted up is a means of healing like the bronze serpent (John 3:14). It becomes extraneous. The fact that the cross discloses Jesus as the King of the Jews (God’s messianic identity), the Son of Man and Son of God, the true Prophet and Priest, all in event of the New Exodus, New Passover, the day of the in-breaking kingdom (Daniel 7), all that is shoved off as the husk to be peeled back to get to PSA. If it is skin and not backbone, why are these themes the very substance of the narrative in the four Gospels? The New Testament does not think in “theories.” It thinks in rich figures.

The Gospel of Mark fundamentally understands the cross as something Jesus’ disciples must do as well, which I find PSA often undermines (the cross is something only Jesus as sinless does). In Mark, Jesus is not propitiating God; he is giving a ransom to the dark powers, redeeming people from demonic slavery (Mark 10:45). And if the punishment of sin is merely death, there is no reason why Jesus had to die on a cross or be tortured. He could have died at home in his bed. Jesus is living out his teaching of becoming last for his disciples to follow, forgiving when sinned against in the most ultimate way, against the demonic forces of betrayal (the people/disciples), religious hypocrisy (the temple), and empire (Rome). It showed that God’s character and our character is not one where we inflict eye-for-eye, but turns the other cheek and blesses our enemies (this is central to Peter’s atonement theology in 1 Peter 2:20-25). This kind of love is the in breaking of the kingdom of heaven itself. Many conservatives miss that for the New Testament and the early church, unanimously, the cross was teaching Christians non-violence as the primary response to evil (see Ron Sider’s book).

Perhaps that is too complex for some. Let’s just stick with one reading. Young, I think, helps those that hold to a PSA word the doctrine more carefully (for an excellent modern statement of PSA, people should read Pannenberg’s in his Systematic Theology). Pop PSA too often makes God the problem, and no one should be happy about that. The cross came to heal us, not fix God’s wrath. The cross is not Jesus in his love saving us from the wrath of God the Father. Jesus is providing a way that we are not punished ultimately, yes, but it is not Jesus saving us from the Father. This severs God’s being. All of God is loving, including the Father, and all of God can be wrathful, including Jesus.

The Father did not abandon Jesus on the cross. This misunderstands Psalm 22, which is not about a sinner but about the persecuted righteous, the messiah, crying out to God for vindication (which the resurrection answers). This was important to the martyrs of the early church. The cross is the call to martyrdom (this is why Stephen’s stoning in Acts mirrors Jesus’ crucifixion in Acts), and the martyrs will enter eternal life. The Cross is Jesus’ way, God’s way, and also our way. It is the way to heaven.

God was fully present in Jesus at the cross. God was at one with sinners as the Son is showing the cross-shaped love of the Father for sinners. God in his love, one with Jesus, bore the penalty of the law, which was not functioning according to God’s will for it (so says Galatians – it was hijacked to only create condemnation, not grace). This tangibly shows that our sins were forgiven, that God loves sinners, and Jesus rose from the grace on the third day to show that the curse of death had been beaten. This is why the gospel has everything to do with the resurrection in Acts 13. So, here Young I think invites us all to word our doctrines of atonement better.

Religious inclusivism: The Jesus character in The Shack references how he is using all systems of religion and thought to being people to the Father. Some accused Young of pluralism. I think this is simple missional contextualization. God meets us where we are at, using the concepts we are used to. Think Don Richardson’s Peace Child.

If it is not that, I would insist, that some kind of religious inclusivism (that God’s mercy does extend beyond the bounds of the church) is completely acceptable. I would point out that religious inclusivism is implied in Acts 17, where Paul insists the Athenians are actually worshiping God already as the “unknown god” on one of their altars. Paul then invites them to put away idols and see God more clearly in Christ. He even quotes a pagan poet as evidence of this truth, that all people are God’s children. The Bible has an intuitive awareness that there are those that are outside the covenantal relationship with God that do in fact get it and do in some way participate in the kingdom of God, whether Melchizedek in the OT or the centurion in the NT. This does not undermine the missionary call of the church to make Christ fully known. While Christ is the only way, St. Justin Martyr, a second century apologist, held that if the Logos is eternal, ever-present, he is using all things everywhere to bring people into knowledge of himself. If they do not hear of Jesus explicitly, it makes sense that God, in his mercy, would judge them according to the amount of his truth they were told and accepted. There are, of course, difficulties with this view, but no more than the assertion that those who have never heard the Gospel will perish without any chance of believing. Call it liberalism if you want, but at the end of the day, inclusivism is the oldest view of the church, espoused by a man, one of the first public defenders of the faith, who also gave his life for the faith.

God as universal father: Central to Young’s theodicy is that God is a loving father to all people, trying to bring even Missy’s murderer to repentance. There are some that deny this truth despite it being explicit in Acts 17. Clearly they have never read Athanasius, On the Incarnation, who sees God universal fatherly love as part and parcel with the incarnation. I would argue this truth is the bedrock of Old Testament ethics and central to the Gospel as Paul sees it in Acts 17. I have argued for it at length here.

Universalism: The final objection I saw is that The Shack is universalist. This is true, not going to deny that. Young is a universalist, but I would point out that there are forms of universalism that are considered historically orthodox. Only one form was condemned at the Council of Constantinople. It was highly speculative and relativistic: “God will save everyone, so who cares!” There are noteworthy universalists that were upheld as orthodox like Gregory of Nyssa or Julian of Norwich. Norwich held to a hope that “All will be well.” It was a universalism of mere prayerful hope, which i think most of us do have, particularly at funerals where someone died under tragic circumstances. At the end of the day, we are all in God’s merciful hands, and we pray that the mercy we were shown as sinners will be the same shown to everyone else.

Nyssa is a more important case. Many western believers do not know him, but he was the most important bishop and defender of orthodoxy of his day; the “Flower of Orthodoxy” was his title. He confidently thought that universal salvation was the only logical possibility of God’s total victory over sin. He was not corrected because he was robustly biblical in his views and his doctrine lead him deeper into prayer, mission, and obedience to Christ. If we know a tree by its fruit, this sounds like what good doctrine should do! You might insist that there are passages in the Bible that speak about eternal punishment (he would insist that too), but what cannot be argued against is that Nyssa’s arguments were read and accepted by the community of the faithful. Their decision might be fallbile, of course, but the fact of their decision makes the interpretation plausible, the acceptable range of Christian faith. So entrusted was his judgment that he was a final editor the Nicene Creed (which notably says Christ will “judge the quick and the dead,” it does not say how!). Historical facts are historical facts. If orthodoxy is the historic bounds of what the creeds mean for acceptable reading of Scripture, there are versions of universalism that are and have been accepted.

Now, perhaps you do not agree with these readings, that is fine, Augustine would have probably hated Nyssa, but at the end of the day, both were accepted. That is the bounds of orthodoxy. Those that hold at the possibility that all may be saved and those that hold to the possibility of eternal punishment are both in those bounds. I would argue that both need each other to counter their extremes. We can never take God for granted, and we can never give up hope on sinners.

This is the scandal of evangelical orthodoxy: it has forgotten so much of this history and reflection on Scripture. It has forgotten the breath and beauty of what the saints have to teach us.

Sometimes the people pointing the fingers have three fingers pointing right back at them.

For sake of argument, take a hardline Calvinist like John Piper. Now I think this guy has character in spades, and I do think he is a legitimate Christian, a great preacher and teacher, but if we are going to play the heresy hunting game with historic orthodoxy, I often get confused at the free passes Calvinists give themselves.

Piper, like most Calvinists, is an overt double-predestinationist, the idea that God elects some to be saved and others not, without any choice in the matter.. While a type of universalism was condemned (and many may accuse me of splitting hairs when I say only one form was condemned), so also was a form of double-predestinationism. Double predestination was seen as undermining freewill and God’s love, something that all the fathers saw as the supreme characteristic of God. Augustine’s radical follower, Gottschalk, was condemned at a local council for holding this, whose decision was treated as universally acceptable. Calvin was highly influenced by this form of radical Augustinianism. Yet, Calvinists really don’t want to talk about this.

Piper has gone on to insist that since God is fundamentally sovereignty (not love as the church has universally held), God causes evil for his own glory. To me this is a perilous opinion. How is God holy if he causes evil? If God is in Christ and Christ is sinless, I have a hard time thinking God would commit a tragedy humans are bound by the Word of God never to do in order to be holy. Also, I have heard him say that he cannot recite the entire Apostle’s Creed because he does not think Jesus descended into hell. He has reasons for this (a peculiar reading of 1 Peter 3), but the matter rests: he cannot affirm even the most basic statement of Christian orthodoxy, yet all his pals are okay with this.

Why is it okay? Well, the Bible is able to correct what we think is traditionally orthodox, which is what I think he would insist. I would affirm that too, but that means the term “orthodox” can become molded by the wax nose of biblical proof-texts. In principle anyone who argues something with bible verses against a creedal norm cannot in principle be condemned. Arian had biblical reasons for his theology, so again, the definition of orthodox as a historical descriptor must be maintained, even if modestly. Perhaps Piper is biblical, but not orthodox. Is he comfortable with this? Or perhaps orthodoxy is being applied with an uneven standard.

Perhaps orthodoxy is more than words.

I bring this up to remind the reader that I do think both Young and Piper are legitimate Christians, both of which with their respective imperfections. I am merely using them as foils in the naive hope that one day we might all actually have grace on each other. Perhaps a foretaste of the kingdom of heaven would be to have people of each other’s ilk coming together and just saying, “I get where you are coming from. I do see Christ working in you.”

Perhaps propositional orthodoxy is just one tool to gauge and nourish our relationship with God among others. After all, “If you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:9). The second part is perhaps most important and it is in the heart.

Yes, doctrine is important, but remember that Peter confessed Jesus to be the messiah, yet he was then rebuked because the deeper meaning of that for Peter was a notion where it was a scandal that Jesus had to go to the cross. His correct confession did not save him from denying Jesus. Only Jesus’ grace saved him in the end. Words can only go so far. Good doctrine nourishes relationship with Christ and living out Christ, but it cannot replace it. There is no verbal test for having a heart that follows Christ. Only discernment can see if a person has a heart of humility, love, and forgiveness.

I met Paul Young once at a conference. He is a remarkably down to earth and a genuinely, humble guy. He told us that a speaking engagement of his was protested by other Christians. In the heat of the day, some of them were fainting from the heat. So, he brought out some water to them personally. They did not even know who he was, so he struck up a conversation. He revealed his identity to them, and asked, “Is there a single person here that has read my book?” Not a soul. He kindly asked if they would at least do that. He did not have a problem if they disagreed, but he would hope that they at least listened. They shrugged. As he went inside, he heard them go right back to their angry chanting.

I know some people that have great “theology,” but frankly do not have a relationship with Christ. They honor God with their lips, but their hearts are far from him. I know some people that have the heart of Christ, following him daily, that frankly believe some pretty erroneous stuff. Personally, if pressed, I would take the later over the former. I’d take a Christ-like heart over a person with Christian ideas.

So, here is the scandal of evangelical orthodoxy, (it by no means applies to all evangelicals): a tradition that has often become so narrow and detached from the rest of historic Christianity, members of it anathematize positions that Christianity has long held. The obsession with being correct, its isolating and alienating mode, ironically, can deafen the ear and corrupt the heart, the true source of relationship with Christ and with others.

Don’t like the movie, The Shack? That is fine. It does have its cheesy moments. The book is not fine literature. Young is no Dostoevsky. Condemn it; refuse to read it; refuse to be open to what a fellow believer is trying to show you about Jesus, and frankly, you are missing an opportunity for a movie with a clear depiction of the Gospel to impact people. Your loss and others. But it is worse than that…

When it comes to The Shack, Paul Young might not have all his doctrinal ducks in a row (I wonder who next to God perfectly does), but it should be apparent that he does follow Christ and deserves the decency that implies. So many times Christians shun each other creating fractions in Christ’s body. We bicker while his body bleeds.

If to love a person in part is to listen to them, I know that the close-minded are often the close-hearted. If the summary of the law is love God with your entire being and love your neighbour as yourself, we have a lot of half-Christians.

As Paul tells us, “The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself in love” (Gal. 5:6).

Perhaps the scandal of evangelical orthodoxy is also the scandal of evangelical charity, a scandal we are all implicated in.

The Shack (Part Two): The Ironic Move from Calvinism to Orthodoxy

I have heard some really vitriolic criticisms of the movie, The Shack.

I am reminded of the parable of the emperor’s new clothes. A foolish emperor commissions new clothes to be made. They were invisible, a deception on the part of the tailors, but they tell the emperor that anyone who thinks they are invisible are foolish. So the emperor pretends he can see the clothes and scorns anyone that does not. On parade, an innocent child points out that he is naked, and the jig is up. The emperor realizes he is in fact naked.

Paul Young is that child, I think. The emperor is evangelicalism; his clothes the pretension to orthodoxy. Our children know our flaws better than anyone, and Paul Young, as a child of evangelical thinking, a pastor’s/missionary kid, is speaking from the inside. He is not an outsider.

Some of Paul Young’s testimony resonated with me. I was raised with a very conservative theological paradigm. I went to seminary, where we liked to joke, “Of course, we are fundamentalists, we just aren’t as angry as those other people.” But the truth was we were angry too. Anyone that held beliefs different from us, if they were significant, were wrong and worse than that, dangerous.

I have learned there is a big difference between “right belief” and “believing in the right way.”

Some of the biggest critics of The Shack have been Reformed Christians. Now, these Christians are our brothers and sisters. They often don’t recognize that, but that is on them not us. I’d prefer to take the high road. We have the same Gospel, just different particulars, but I would point out there are some particulars that I think are deeply problematic.

I do not speak as an outsider on this. In college, I loved listening to John Piper. I read Calvin’s Institutes and I thought Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology was the greatest contemporary work to put theological pen to paper.

Now, I think the only reason I thought that was because I had not read much else. Since then, I have read at least one systematic theology every year. For me I moved beyond some of my more ultra-conservative convictions because they fundamentally could not stand up to either the Bible, historical Christian thinking, or the phenomena of life itself. I’ll explain…

For Calvinism, since God elects some to salvation and others not, and there are those Christians that claim to be “Christians” (like those Catholics and liberals and people that watch HBO) but are not (grace was not enough for them), I had to be hyper-vigilant theologically. I found myself always angry and annoyed at someone’s theology, even disgusted. I did not want them to contaminate me. If there were people that were not Christians but thought they were, the only way I knew I was saved myself was to always keep articulating every question I had theologically, ever more precisely, and to stay away from those that differed (you can read more about my journey in learning to accept other Christians here). Questions over infra-lapsarianism or super-lapsarianism became faith crises as to whether or not I actually believed God was sovereign and therefore whether or not I was saved. Discussions like this all became slippery-slope arguments. Arminians denied God’s sovereignty; open theists God’s impassibility; egalitarians, God’s authority. I was very good a pointing out the proverbial speck in another, ignoring the proverbial log in my own.

I could not reckon with the fact that there were sincere, biblically-minded Christ-followers that did not think the same things as me. See, when I looked at a biblical passage, and had an interpretation I thought was by the Holy Spirit, I could not doubt that. Everything hangs on certainty. I have often said that a fundamentalist cannot ask whether or not they are truly wrong on a core issue of doctrine, because to do is to doubt God and to invite doubt about one’s salvation assurance. Self-fallibility is too risky, even if it is true.

In this scheme, I did not believe in justification by works, but that just meant I was saved by doctrinal works. I was certain of my salvation because of the correct ideas in my head.

This proves potentially fatal if you ever encounter an important yet ambiguous text, which was often in seminary, or change your mind, or just don’t know what to think. The Bible became a scandal to my own theology, whether it was the unsustainable idea of its inerrancy, the refusal to admit the existence of woman leaders, or passages that did not fit an impassible God. As I began to see some of my theological convictions being contradictory, I felt like I was losing my salvation.

In one summer, while that was happening, my “shack” occurred. My father died of cancer; my mother was also suffering from cancer. Several friends of mine went through severe moral and faith crises, which for their sake I will not go into (you can read more about the whole experience here). I was left penniless, working at a Tim Horton’s on night shift, wondering if all this Christianity stuff was even true.

I ended up having a remarkable shift where God encountered me in the abyss of my confusion. I realized that if God is love and God is in Christ, then my ideas of faith can fail, but God will still have me. It was a profoundly mystical experience.

That lead me on a journey to rethink my faith, since I suspected there was more to it than just one tradition that no longer nourished me. This is a hard thing to say to some of my Calvinist friends, who I do consider my brothers and sisters, but I find that this theology is so intellectually and biblically problematic that it induced a faith crises for me, yet still nourishes them.

Nevertheless, that summer I began to I read deeply. I went to the University of Toronto soon after where I got to study under so many different voices. In high school I was a fundamentalist, in college I moved to being a conservative evangelical, in seminary I felt like I was becoming increasingly liberal, in post-grad studies I read deeply in postmodernism and mysticism, by doctoral studies I found myself gravitating to the school sometimes call “post-liberalism,” which lead me to do my dissertation on James McClendon, a Baptist narrative theologian.

Along the way, I started reading church fathers, mothers, and doctors. These are the most esteemed thinkers and saints the church has looked to. I gravitated to the mystics: Dionysius, Nyssa, the Cloud of Unknowing, St. John of the Cross, Julian of Norwich, and Meister Eckhart, but also Irenaeus, Aquinas, Athanasius, Anselm, and Augustine, etc.

One thing that I started noticing was that what I thought was “unorthodox” was widely held by those who were actively bound by creeds. When I told them about my upbringing, they looked at me recoiling, noting how unorthodox it was.

I found that, ironically, the narrow view of what I considered orthodox was actually not viewed that way by those who had read deeply in the tradition of historic Christianity and had strong conservative commitments to historic orthodoxy. What is “orthodox” here is the bounds of acceptable biblical reflection that the church over 2000 years has developed, using church fathers and doctors, councils and creeds. The sad thing was that the over-protective, arrogant, isolated, and suspicious mode of my past beliefs ironically made me closed to something the greater sweep of Christianity held to be appropriate.

Bonhoeffer once said that those that cannot listen to a brother or sister will soon find themselves unable to hear the word of God also. I think this statement is applicable.

Here lies the irony of those that criticize the “heresy” of The Shack. The notion that Young has moved beyond conservative evangelicalism is not abandoning orthodoxy; it is coming back to it!

I’ll explore this further in my next post.

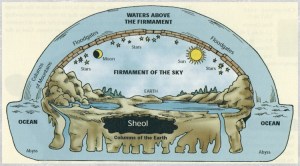

Why Genesis One Does Not Teach Creationism

“One does not read in the Gospel that the Lord said: I will send you the Holy Spirit who will teach you about the course of the sun and moon. For He willed to make them Christians, not astronomers.”

– Saint Augustine, regarding Genesis chapter one

Many of my fellow believers are creationists, who hold that Genesis chapter one should be read as teaching a doctrine of how the world was scientifically made. While I respect the sincere faith of these believers, some are even in my church, I also see many Christians, myself included, encountering significant faith crises, because of the assumptions of that perspective. Many creationists see it as the opposite: that evolution will erode and destroy one’s faith. For me and many other Christ-followers, it simply hasn’t. For me, it is mostly because I found that Genesis one should not be made to comment on the scientific composition of the universe. Here is a reflection on why I think Genesis one is best understood as offering a theological narrative: timeless truths about God and creation delivered in a culturally bound way.

There are some very good reasons not to take Genesis one as offering a scientific description of the creation of the world. Not doing so, I think, is the most consistent way to interpret it. This is because there are pre-modern notions about the cosmos that these text assumes. In fact, I will go so far as to say that if we do take it as a historical description of the material origins of us and the cosmos, if we make that the truth of this text, we force the text to contradict itself, reducing a literalistic strategy to absurdity.

So, the following eight exegetical points attempt to point out the problems of a creationist approach. Because the text assumes a geo-centric cosmology, it cannot be used to support creationism which does not hold to these details. I am doing this without offering a full positive doctrine of creation (which is another argument that I will give later). However, trust me, I do think Genesis one is God’s Word and that the universe is God’s creation. But it is God’s Word in proper literary context, understanding the cultural climate it was written in. I believe in creation. I believe that Genesis one teaches us about creation. I just don’t believe in “creationism” as an idea that tries to extract science into this narrative or things all of the aspects of these narrative are applicable today.

As I said, my argument is an reducio ad absurdum. Creationism, by its own uneven exegesis (or more accurately is consistent neglect of what the text literally says), is an interpretation that collapses into self-contradiction necessitating a different interpretation, a reconsideration of interpretive principles. So here are the eight interconnected arguments or features:

Creation from Water?

The opening verses describe the heavens and earth as “formless and void” yet the spirit of God hovers over the waters of the deep. Before everything else is created, there is water. Before there is time, planets, stars, there is water. That seems odd. Why is that? Is water the eternal, primal sub-atomic substance in which all things were constructed? Does this passage, as some suggest, contradict creation ex nihilo, the notion that God created the world out of nothing? No.

Water was a symbol of nothingness. The Mediterranean Sea was thought to be an “abyss.” Why? If a sailor sank into the depths of the sea, they would disappear into what would seem like bottomless black nothingness, a void. Beginning with water is a metaphorical way of saying the world was “formless” and “void,” and so, God created the world out of nothing.

Notice right off the bat then that choosing to see metaphor rather than concrete descriptions makes the images in the text make way more sense. It makes them much more meaningful. It has a better interpretive fit.

Earth then Universe?

Next we see that the creation of the earth precedes the creation of the very universe it is supposed to be situated in. This should tip us off that this is not a scientific description. In fact, we commit violence to the text by reading out modern assumptions into it. By all accounts the Sun is older than the earth, and the earth (as well as the moon) all formed because they were in orbit around the Sun.