Tagged: cross

Seven Final Words: Into Your Hands

“Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” Luke 23:46

Jesus at the cross began by praying; here he also ends by praying.

These are often words spoken on people’s deathbeds and at funerals. They are profoundly comforting words. They comfort because they remind us of the sobering but reassuring truth. One day, whether unexpectedly or at the end of a long life, we will die. Our physical lives will end. All that we are, had, and hold on to will cease.

This is sobering because we realize the truth that we cannot save ourselves. We cannot preserve ourselves. We cannot control the very foundation of our lives. Millionaires have died in car accidents and cancer just like the rest of us.

We cannot take this world with us. Celebrities pass away and their fame eventually with them. You can be buried with your money, if that is your will, but that is not you anymore in that casket anymore than that money is useful. What we are and have, ultimately and finally, is not up to us. It is up to whatever or more importantly whoever lies thereafter.

This is why it is reassuring, even liberating. It reminds us that at the end of the day, whoever we are, it is all in God’s hands.

Here, God in Jesus Christ is modeling for us the very essence of faithfulness: trusting God in the last moment of life, at uncertain threshold of eternity.

One way or another our lives are in God’s hands, the question is what will God do with us?

As Jesus said these words, we was dying on a Roman execution cross for the crime of blasphemy, while sinless, he made himself a sacrifice for sin. He gave himself up for us. I would emphasize that he did so, completely. We do not have to fear death because Jesus faced that fear for us.

He had the promise that God is in him and the Father will resurrect him, however Jesus was fully divine and fully human: prone to doubt, prone to uncertainty, prone to anxiety and fear. You can imagine the question is his human, all too human, head: Will my Father be faithful? Will he come through? We have already meditating on his cry feeling forsaken.

So, the comfort of these words must also be kept side by side with the pain of the cross, the willingness of the cross. It is a willingness that seems to admit that Jesus was willing to not only die trusting the Father but also embrace the possibility of the ice-cold silence and darkness of death and hell.

Understanding this fear perhaps explains why he pleaded that this cup may pass, sweating out drops of blood. “But not my will but yours be done,” he prayed. And so again, into your hands, I commend my spirit, as into your hands, all our spirits. It is always in God’s hands, not ours.

Just as he says this, Jesus breathes his last. Jesus dies. The Son of God died. God was found in death. God bound himself to the fate of death. God of infinite joy and life came into the finite space of wretched mortality.

When we think we are sinful and unclean, when we suspect that in our final breath we will disappear in judgment before an exacting God of judgment, we must remember that God died our death penalty. God entered our mortality. God became a rotten corpse, the very object of the consequences of sin, the very object of uncleanliness according to the law. The incarnation was complete, completed in the act of perfect atonement.

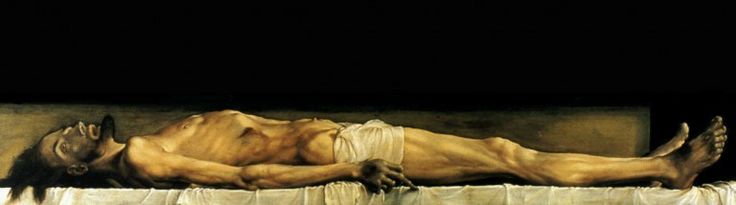

No piece of artwork shows this better than Holbein’s the Body of Dead Christ in the Tomb from 1520. Holbein depicts the remnants of the crucifixion on Jesus’ boy: the mangled, pieced, blacked hands, the stretched tortured body, the limp and lifeless face.

At the cross that mission was accomplished. Sin, death, corruption was defeated, but it was through Christ’ willingness to die.

Luke’s gospel reads, “Having said that, he breathed his last. When the centurion saw what had taken place, he praised God and said, ‘Certainly this man was innocent.’ And when all the crowds who had gathered there or this spectacle had saw what had happened, the returned home and lamented.”

Matthew records that at that very moment, the curtain of the temple, the divide between God and man, was torn asunder.

If God is in Jesus Christ, he will not leave Christ to rot in the grave. And the Father didn’t. He rose to new life on the third day. God is love and hope and healing. As we are in Christ, we have the hope that, as everything is in God’s hands, one way or another, we can rest assured they are in good hands, the hands that are mighty to save us.

Final prayer:

Father, we pray recognizing the cost of the cross. We pray trying to understand its pain and shame. We will never understand its full weight, but give us enough understanding to receive it into our hearts. We pray that we would not just hear about the work Christ did, but receive it. We pray would not just look upon the cross, but take it up ourselves. That is taking up the life the cross demands of us, the love it embodies, the truth is sacrificed for. Do not let us leave this place without our heart changed with a new commitment to living out the way of our Lord Christ. Thank-you for your justice, mercy, and love. Thank-you that your cross comes with the promise of the resurrection. Amen.

Seven Last Words: Thirst

“I thirst” (John 19:28)

In the beginning as Genesis two tells us, there was a stream that bubbled up and watered the earth. From the clay of this stream the first man was molded, from its water Eden was irrigated, and from there, the text says, out of the garden the stream became four great rivers. Here is the archetypal river of life, fountain of salvation.

The human body is about 50-80% water, and doctors recommend that a person drink about 2 litres of water a day to be healthy. It is no stretch of the imagination that we can say that water is life.

Not surprisingly, there is a persistent image of water in Scripture as a source of cleansing, purifying, and revitalizing.

John, a master story-teller, makes use of the theme of water and thirst throughout his Gospel. Disciples are baptized in water. Those entering the kingdom of heaven are born of “water and spirit” (Jn. 3:5). Jesus poured out water to wash the disciples feet, the quintessential act of servanthood.

One instance is particularly applicable. Near the beginning, a woman comes to the well in Samaria, who has been married five times and is living with a man not her husband. Jesus meets her there, and asks her for a drink. She protests, saying the well is deep. Jesus uses this to tell her that there is water that will make her thirsty again, and than there is living water form which she will never be thirsty again. While naïve and uninitiated, she tells Jesus that whatever this is, she wants this water.

She does not understand what this water is, but she is thirsty for it. She is thirsty for water that is more than water. She is thirsty for compassion, for love, for forgiveness, for truth.

Of course, this water is eternal life, and this water is found in Jesus.

The Samaritan woman is, as we all are, thirsty for salvation.

Psalm 42:1: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God.”

Yet, here on the cross, Jesus, the God-man, the one who is life, who is living water, is now thirsty. In this beautiful use of irony, water does not mean water, and thirst does not merely mean thirst: Thirst is the thirst of the soul. Jesus becomes thirsty.

As Jesus cried out in thirst, they gave him sour wine. The offering was not a malicious gesture as sour wine was considered better for quenching thirst, often used by soldiers like modern-day Gatorade. But Jesus’ thirst here is more than just thirst.

Psalm 63:1: “God, are my God, earnestly I seek you; I thirst for you, my whole being longs for you, in a dry and parched land where there is no water.”

The Scriptures say, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law, having become a curse for us” (Gal. 3:13). “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us.” (2 Cor. 5:21). Christ, the son of God, the son of man, died representing all humanity before God and representing God to all sinners. He died in our place. He took on our pain. He took on our thirst.

His parched throat mirrors the desert wasteland of our souls.

In John’s gospel, as he died, after crying out “I am thirsty,” a soldier pieced Jesus’ side and it says water flowed out. Here we see another allusion to Psalm 22: “I am poured out like water.” Water flowed out of the one whom was thirsty. Through Jesus’ death, water flows. Through Jesus taking our place, God dying as a sinner, our souls will one day drink of the river of life.

So the vision in Revelation 22:1-3 says,

Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb down the middle of the great street of the city. On each side of the river stood the tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. No longer will there be any curse…

In this passage thirst, water, and the overcoming of the curse are intimately connected. We are all thirsty. We thirst for Jesus. Jesus is that water that restores us to vitality perfectly. We know this because Christ bore our curse. Jesus is the only thing that refreshes our parched, dry souls.

Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount, “Blessed are those that hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.” Jesus made this promise, and here on the cross, he cries out thirsting for justice himself, dying from the oppression of a corrupt religious and political system. Yet his thirst was not for vengeance, but for the healing of sick, sinful souls. So Revelation depicts a day here water flows from the New Jerusalem “for the healing of the nations.”

Jesus is righteousness. Jesus is truth. Jesus is forgiveness. Jesus is living water.

And because of the cross, because Jesus chose to be at one with the thirsty, to thirst in our place, we are free to drink of the water of life; We are free to drink of the resurrection reconciliation.

So Revelation 22:17 says, “The Spirit and the bride say, “Come!” And let the one who hears say, “Come!” Let the one who is thirsty come; and let the one who wishes take the free gift of the water of life.”

Father,

We realize that we thirst for you.

We may think that we thirst for other things – money, safety, popularity, health – but it is you that we ultimately thirst for.

Thank you for becoming thirsty, taking on our thirst.

May we drink of the water of the river of life that flows from Christ who died in our place.

May the day come quickly that we see all nations gathered to be healed by the water of the river of life.

Let all who are thirsty come to you, Lord Jesus.

Amen.

Seven Last Words: Forsaken

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34)

In his book, Night, Elie Weisel gives his bitter account of the Holocaust, an event so horrifically evil it unsettled the very core of his Jewish faith. He was only a boy when he saw the execution of an innocent man, starved, emaciated, beaten, broken – broken of his very humanity. He was robbed of his dignity by people devoid of their own humanity, the Nazis.

This man was hanged in front of all the other prisoners: the poor man was made into a spectacle of the Nazi’s brutality as the audience was made to watch, feeling the full measure of their own powerlessness. Weisel, a boy, was made to watch.

As this happened, someone called out, “Where is God?” That man had had enough, the injustice caused him to cry out at the risk of his own execution. “Where is God?!” As if to say: How can he not be here? How could he not intervene in a moment like this? The crowd could give no answer as he indicted God in a crime of cosmic proportions.

“Where is God?” the voice rang out again, again and again.

Elie Weisel, a young man at the time, felt in his heart the only possible explanation: Where is God? God is dead. He died there in those gallows.

Weisel saw this admission as the very moment his faith collapsed into a bitter semi-atheism. His hope in God was shaken.

But as Weisel reports, he did not lose faith, for while he felt hurt by God, the prospect that there was no God at all rendered the events of the Holocaust even more tragic: no God to denounce the evil as fundamentally wrong, no God to command compassion rather than indifference, no God to offer the promise of restoration.

Weisel’s shaken faith, I think, is an honest faith. Faith calls for nothing less than honesty about ourselves and our world, and that honestly about our world calls for nothing less than the honesty of being deeply upset over the tragic injustices of this life.

But to have that honesty in faith means addressing that frustration and lament before God as Jesus did: “My God, my God why have you forsaken us?”

This phrase comes from Psalm 22, a psalm written by David, who was a righteous man that was attacked by his king, his friends, and later, even his own family. He spent much of his life on the run, hunted like an animal.

One way to understand the cross – perhaps the most basic way – is to understand that Christ died, “according to the Scriptures” (cf. 1 Cor. 15:3-4). Jesus embodies the story of Scripture. He is the word of God.

He is the suffering servant of Isaiah 53: “But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed.” He is the “stone that was rejected that is now the corner stone” (Psalm 118:22 cf. 1 Peter 2:7). He is the perfect Passover lamb, slain as a sin offering for us, etc.

Jesus fulfills this scripture as the rest of the psalm shows:

Dogs surround me,

a pack of villains encircles me;

they pierce my hands and my feet.

All my bones are on display;

people stare and gloat over me.

They divide my clothes among them

and cast lots for my garment. (vv. 16-18)

In claiming these words as his own, he is not merely fulfilling the Scriptures. He is showing God’s solidarity, his oneness, with all the forgotten of this world. Jesus in crying out in forsakenness, embodying the cry of the oppressed, the abused, the victimized, the neglected, the humiliated – all who feel that God was not there when they needed him. Listen to the rest of the Psalm:

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from saving me,

so far from my cries of anguish?

My God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer,

by night, but I find no rest (vv. 1-2)

But I am a worm and not a man,

scorned by everyone, despised by the people.

All who see me mock me;

they hurl insults, shaking their heads.

“He trusts in the Lord,” they say,

“let the Lord rescue him. (vv. 6-8)

I am poured out like water,

and all my bones are out of joint.

My heart has turned to wax;

it has melted within me. (v. 14)

This is the lament song of a soul in despair. This is also the words of God in Christ.

In Christ, God knows what it is like to be abandoned, betrayed, tortured, humiliated, blamed, and executed.

Jesus, in his trial and crucifixion, was the subject of personal betrayal: his best friends and students ran, denied him, and even received money to betray him.

Jesus, in his trial and crucifixion, was the victim of religious corruption and abuse. He was accused of blasphemy for his message of forgiveness: that God is with us, sinners. He was tried falsely by corrupt priests who didn’t want their sins exposed or their power taken away. As John 8 tells us, Caiaphas, the high priest, ironically saw Jesus as his sacrifice to save their religion.

Jesus, in his trial and crucifixion, was the target of political oppression. He was brought before the magistrate, Pilate, who ultimately cared only for order at any cost. So, he gave Jesus over to his psychotic soldiers for torture, humiliation, and finally execution by the slow death of the cross.

The cross is a rare kind of anguish. It is the slow death by bleeding out from the torture and nails. Hanging on the nails meant one’s diaphragm would be stressed, causing the person to gasp for air. The subject would hang there starving to death, slowing hallucinating in a delirium of despair as people stand there and mock. Nailed there, few pictures of the atonement render it accurately: few picture the victims unclothed and naked, exposed to desert sun that would blister exposed skin. (Ironically, no crucifix renders Jesus naked – an accurate depiction of the cross is still too scandalous, even Christians!) And the nakedness of exposure was more than physical: hanging there naked, the victim was exposed to the scoffers, jeering, removing whatever dignity remained. Jesus had the added pain and humiliation of a thorn crown pressing into his head and a sign above, mocking his claim to the throne of David.

How could God let this happen to Jesus? How could he have forsaken him? Where is God?

The answer is right there. God was right there. God was in the man who was godforsaken. God revealed that he is with those who feel forsaken by God.

Jesus, Immanuel, “God is with us,” is here as God bound to our fate, our death, our despair, our pain, our sense of the absence of God. He loves us so much he stands with us in our darkest moments.

This does not make sense by our worldly logic, but this is the logic of God. Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it well when he said, “Only a suffering God can save us.” Only love that is willing to suffer with a victim, feeling their pain, willing to take their pain as his own, can disarm the anguish of suffering.

Jesus cried out, “My God why have you forsaken me?”

Jesus deserved justice’s vindication, but he gave it up to live in solidarity with those whom justice has forgotten.

Jesus deserved the throne room of heaven, but chose a crown of thorns.

Jesus deserved to inhabit heaven, but instead he chose to harrow hell.

So, we return to our Holocaust anecdote: Where was God as an innocent man died in the gallows of the Holocaust?

God was with that dying man. He was in that dying man. He was dying for that dying man. God is that dying man, “slain before the foundation of the world” (Rev. 13:8).

God did die that day, but not in the sense that would lead us to atheism.

God did die that day, because he is love; he is suffering love; he is a God that refuses be far away from those who feel forsaken.

God refused to stand far off as his beloved children suffered. It is that same refusal of a God that chooses to suffer with us that refuses to leave suffering forever forsaken in our broken world. If God suffers with us, we know that God did not cause our suffering. If God suffers with us, we also know that he would not will this suffering to be without end. A God of love is a God of hope for us.

We know this because three days after the cross, Christ rose from the grave. Suffering will stop because the cross leads to resurrection.

So the Psalmist affirms in his suffering that one day…

The poor [i.e. the oppressed, the abused, the abandoned] will eat and be satisfied;

those who seek the Lord will praise him—

may your hearts live forever!

All the ends of the earth

will remember and turn to the Lord,

and all the families of the nations

will bow down before him,

for dominion belongs to the Lord

and he rules over the nations. (vv. 26-28)

There will be a day when suffering stops, when tears are wiped away, when hunger is satisfied, when wounds are healed, when pain turns to praise, when repentance and reconciliation reigns.

There will be a day of perfect justice, perfect mercy, and perfect peace.

That day is coming because the God who died on the cross, rose from the grave. Death could not change the impassible character of a God who is boundless life.

The cry of the cross was answered with the triumphant joy of resurrection. Let’s pray…

Father,

We ask with Jesus sometimes, “Why have you forsaken us? Why all the injustice? Why all the destruction? Where are you?”

God, remind our broken souls that you were with us in the times that seems like you were absent. Help us to look to Jesus and trust that you are not far off. You are with us. You are for us. You bear our pain.

You did not abandon us as you did not abandon Christ. Soften our hearts to let go of that pain and anguish, knowing that you have already taken on that pain in the cross.

Lord, allow the wounds of our past to heal in the same way the cries of Golgotha were answered with the resurrection.

Allow the cross and resurrection to inspire us. Give us the grace to live out what your promises demands. Convict us of the courage to confront the injustice of life with Jesus’ innocence. Convict us of the empathy to confront the suffering of this world with Jesus’ solidarity. We pledge to act in trust, compassion, and hope, knowing that you will restore all things.

Amen.

Seven Last Words: Mother Mary, Brother John

“Woman, behold your son” … “Behold, your mother!” (John 19:26)

While it is easy to see this passage of Christ looking to his mother, Mary, and instructing her to embrace John, the beloved disciple, and John vice versa, as a simply provision undertaken by our Lord to ensure his mother is cared for, these passages offers us glimpses of something deeper. Let’s look at both John and Mary here.

Why is Mary told to refer to John as a “son” and John to refer to Mary as his “mother”? The provisions of care do not necessitate this, yet Jesus insisted. He could have just said, “John, take care of her.”

Some have seen this as Jesus recommending a relationship between Mary and the disciples.In Christ, there is a new family, a global family, of the redeemed that all began at the cross. Mark 3:35 says, “Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.” Here we see the constitution of that family, gathered around the crucified Jesus, listening to his instructions, and so, compelled to treat one another as family.

But it surely meant more than that for John. Mary and John are among the few that actually stayed close to Jesus. They did not flee like the rest of the disciples. John was allowed near the crucifixion site, perhaps because he was so young. We know this because only boys too young to serve in the military could come near the execution site for fear of uprising to save the crucified.

This helps us understand why John sometimes refers to himself as the “beloved disciple,” who “reclined at Jesus’ side.” Peter would have been much older, the eldest of the disciples, possibly. It is also possible that John was the youngest. He was only a boy, small enough to need hugs from Jesus. He may have seen Jesus has a father figure.

Jesus taught us to call God, “Abba” (Daddy). John may well have called Jesus, “Abba.”

John is standing there, watching his father figure die. So, this was more than provision of care to Mary, it was recognition of mutual support. They would need each other. You can understand Jesus’ words now as commissioning the young John. “It is time to be a man, now John, take care of Mary, treat her like your mother.”

As we see John’s writings through the New Testament, particularly in his epistles, John took up this commission well. He was an apostles of family and love through and through. He constantly refers to his congregation as his “little children,” not unlike what he was when he learned his essential instructions from his master.

We know from church tradition that John’s dying words to his church was, “Little children, love one another!” Love shun through John’s writings at all points, especially in passages like 1 John 4:7-12:

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love. God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins. Beloved, since God loved us so much, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us.

His church was his family, and love was his ministry because Jesus was his hero.

Can we look to Jesus like John did?

Now, Mary: Protestants have often forgotten the importance of Mary. We have done this out of understandable reasons: it is out of discomfort with how high Mary is elevated in Catholicism. But as Catholicism raise Mary too high; Protestants are guilty of not raising her high enough.

In church history, veneration of Mary began because of how Mary pointed to a proper understand of Jesus. Jesus died in the flesh (contra some who denied his humanity) because Jesus was born to a human mother: Mary was the guardian of Jesus’ humanity, the theotokos, “God-bearer” in Greek.

But, sadly, Mary was elevated to a kind of co-operator with Christ in some Catholic theology, which Protestants simply feel makes her into an idol. But we should ask is how do we properly adorn Jesus’ mother so that she once again safeguards her son’s high place? We might phrase this better by asking, how does respecting Mary as a mother – us looking to her motherly qualities – how does that bring us deeper into appreciation of Jesus? Or, how does understanding Mary as mother deepen our understanding of Jesus as our brother?

The picture displayed above renders this clearly: eyes too sorrowful to see clearly, but too concerned to look away; hands, clenched praying perhaps both that her son would be faithful to the onerous task she bore him for, but because she bore him, praying pleading with God to relent of the suffering her son is feeling.

To look to Mary as our mother is to look at Jesus’ hanging on the cross, not as an abstract idea, a stale doctrine, a historic account, or an expression of our own sentiments, it is an attempt to see the cross for what it is, and not bypassing it too quickly.

Seeing the cross as our salvation can too readily jump from its tragedy to the benefit we get out of it. We can easily see Christ as suffering on our behalf and we can say, “thanks,” and continue on our merry way. We can selfishly forget the cost of the cross. We can easily look at the cross for what we get out of it, not what God put into it.

When we look to Mary as the mother of Christ, we also look at the cross through the eyes of a mother. Someone’s son died on that cross. Someone’s little boy, her pride and joy, everything she lived for, is being murdered mercilessly, dying that miserable death.

And do you not think that it may have occurred to her that while she knew Jesus was dying for her sins, she would have gladly died in her sons place just to save him from the pain? Don’t you think even that she would have gladly refused her own salvation if it meant saving her little boy’s life?

It is only when we look at the cross through Mary’s eyes do we appreciate the cost of the cross for us. It is the cost of a life more precious than our own.

It is only when we lament the cross through Mary’s tears are we ready to say thank-you to a God that gave so much we will never understand.

It is only through the love of Mary for her Son that we ready to love the world as Jesus loved it.

Lord,

May we love as John loved. May we look to you as our daddy, our father figure. So close to us that we can “recline at your side.” Help us to remember that we are beloved disciples, not just disciples. Draw us closer into the family of God. May we treat your sons and daughters as brothers and sisters. Give us opportunities to be big brothers and sisters to others.

May we mourn for you as Mary mourned. And in our mourning, let us remember the provision that Jesus gave at that very moment, the only true provision against the tragedy of this age: You gave us the church, the family of God. Help us to take care of one another. Help us to love one another.

Amen.

Seven Last Words: Paradise

“Truly, I tell you, today, you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43)

Our world is a world that has closed itself off from the transcendent. We have bought into the discourses of science that tells us the immediately tangible is all there is, everything else is suspected as superstition.

Do not get me wrong, science has earned its place in the world, and many need to listen to its voice more. Science has offered enormous explanatory power for our worldview. In the great feuds between scriptural literalism and science, science will usually win. We have found the sun does not revolve around the earth, that the earth is much older than chronicled, that rain comes from weather systems, illness from poor hygiene, etc.

The world has pushed God out of its purview. God has been viewed as too burdensome a notion to trust.

The events of the primordial church fade into the distance of history. History, itself, seems to crocked a path to see providence. Divine intervention seems like misconstrued co-incidence. Many of the great political advances have been done despite religious influences.

We immerse ourselves in the comforting hum of media noise. Talk of God becomes as rare as genuine conversation itself. Hearing from God becomes as rare as genuine listening itself. An atheism falls over us because we feel the blunt force of divine absence.

Our daily lives, even for many Christians, are often practically atheist. Church becomes an cumbersome ritual. Work is more important than worship. Singing praise to God does not feed a family. Prayer and Scripture reading get sidelined to more relaxing practices: Television, sports, etc. So, we say to ourselves, why bother believe?

However, we deceive ourselves into thinking the modern world was the first to discover doubt, as if doubt was an invention by the same brilliance that discovered flight, electricity, or the theory of relativity. Yet, doubt is not a modern novelty.

The cross was a scary time for Jesus and his followers. The cosmos, let alone their little band of disciples, hung in the balance. The circumstances had become so chancy that most of the disciples deserted Jesus: belief in this man as the messiah was simply too insecure at that moment. Peter initially drew his weapon to defend his lord, but upon realization that violence was not going to resolve the conflict between Christ and the priests, upon seeing his master taken rather than fighting back, unleashing the kingdom of power that he was expecting him to unleash, Peter himself turned to deny Christ, three times in fact. Other disciples deserted him far sooner, unfortunately.

Thus, there Christ hung, condemned, and by all accounts at that very moment, defeated and disproved. Jesus as messiah was no longer a tenable conviction anymore. He did not seem to be bringing in a new kingdom, as prophesied. He did not defeat the Roman occupation, as prophesied. Far from! There he was pathetic, disheveled, beaten into irrevocable submission to the powers he should have pulverized with legions of the faithful, perhaps having even angel armies come to assist. Thus, Pilate, either out of mockery to the Jewish people or out of some deep seated pious guilt over killing a truly innocent man, wrote “King of the Jews” and hung it over Jesus’ head.

If one was to look for a reason to believe in Christ at that moment, one would have looked in vain. The man on the cross was exposed many times over as just a man, flesh and blood, ashes and dust, rejected by his people, betrayed by his closest followers and friends, accused of blasphemy by his own religion’s authorities, tortured and in the midst of his execution by his people’s most hated enemies, the most idolatrous power in existence, hanging there, slowly bleeding out, slowly succumbing to his wounds, to thirst, and to death.

Atheism’s objections pale in comparison to the scandal of Good Friday.

As onlookers mocked and jeered, even a man, a wretched thief, dying the same death as Christ next to him, felt no solidarity with the co-condemned, no compassion for his neighbor in this death, only cynicism and despair. Even the thief on Jesus’ one side mocked him.

At this moment, there seems to be no good reason to trust Jesus. Jesus hung there, discredited.

Would you have believed that Jesus was the messiah then? I know I probably would not have. Sadly, that is because I am a “reasonable” person.

More sadly, is that the only reasonable people in this story are monsters: Judas, who calculates how to profit from Jesus’ arrest; the Pharisees, who have the foresight to plan against possible agitators; the Romans, who brilliantly invented means of rebellion suppression.

And yet, in this moment of darkness and doubt, despair and destruction, one person believed! One person dared to see something more. One person had faith. The other thief, what tradition refers to as the “penitent thief,” dying at Jesus’ side. He believed. He had nothing left to hold back. He could have mocked like the other thief, but he didn’t.

We know next to nothing about this person. The Gospels left him unnamed. Having no hope left in this world, he still says to the other thief, “Do you not fear God? You are under the same punishment.” He admits that his punishment is just, yet Christ’s is not. Christ is innocent and he is not.

At the very end of his life, he is moved with humility and honesty.

But his confession is more radical than that. If one was worried about self-preservation, they would have petitioned far more prestigious powers than a dying messiah.

When no one else believed in Jesus, this man did. And so he simply requests that Jesus would remember him when he comes into his kingdom. He, in the darkness moment of his life, in the darkness moment in history, chose to trust the kingdom is still coming.

This man had perhaps the greatest faith in all history, and yet we do not know his name! But God does. God is not dead because God did not stay dead.

Jesus did promise to remember him. In fact, this man, in his final moments of life, was given the most definitive assurance anyone had before the resurrection: Jesus turned to the man and said, “Today, I truly tell you, you will be with me in paradise.”

Sadly, it is only when we realize that our lives stand on the edge of oblivion that we can feel assured that our lives are in the hands of something more absolute than what this world offers.

Father,

Help us to have even just a fraction of the faith this man had.

We complain about our lot in life, yet we are unwilling to admit our faults.

We so often mock and mistrust your salvation. When we do that, we must acknowledge that our punishment, like his is just.

But we must also cling to the hope of your kingdom of forgiveness.

Remember us Lord Jesus, as you remembered him.

May your kingdom come.

Amen