Tagged: Holy Spirit

One with the Father: A Trinitarian Meditation for Father’s Day

Preached at Valley Gate Vineyard, June 16, 2024 (Father’s Day)

20 “I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. 22 The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. 24 Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory, which you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 “Righteous Father, the world does not know you, but I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made your name known to them, and I will make it known so that the love with which you have loved me may be in them and I in them.” (John 17:20-26, NRSV)

In this passage, Jesus prays for the church, and in this prayer, he speaks about his relationship with his Father, how they are mysteriously one: the Father in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the mystery of the Trinity that the Father is fully God, the Son is fully God, and also the Spirit is fully God, each showing that they are distinct persons and yet, they are one, one relationship in each other and through each other.

Now, I am a theology professor. I get to teach folk about this stuff, and sometimes, let’s just say, students are less than thrilled to dive into the tough stuff. Most grant that there is something about doctrine that is important. This thing called truth; we are all big fans, and so, the Trinity is worth a nod to being fundamental. Now, that can all sound well and good, but it is also quite mysterious and abstract, and who has time to understand all that stuff? Sure, the Trinity is important; sure, it’s fundamental but it is also kind of fuzzy.

That Father and the Son are one, the Son in the Father, the Father in the Son—what does it mean to be at one? What is the Trinity trying to teach us (especially today on Father’s Day)? Isn’t all this oneness talk just impractical abstract mysticism? Are we right to ask, as modern people, is all this really useful?

And while we are at it, isn’t talking about God as a father a bit sexist, a bit patriarchal? Again, we, as modern people, are we right to ask: why should I look to this ancient book called the Bible, a book that has caused wars, sanctioned slavery, suppressed science, and supported sexism? What could we learn from looking at this old language of God as a Father? What can it possibly say to our experience of our fathers and, for some of us, our experiences as fathers and how this relates to God?

One time, I was camping on the shore of Lake Erie with a group of friends for our friend’s bachelor party. Of the group of guys, most were from our Bible college, all except one, who Craig knew from his work. Upon realizing this, my Bible college mates inquired about whether he was a Christian or not. The guy merely said that he “just wasn’t all that religious.” Another guy in the group saw this as an evangelistic opportunity. The conversation frustrated the non-Christian guy. He left and went over to where I was sitting. He was visibly annoyed, and I cracked a few jokes to lighten the mood. We chatted there under the stars, glistening off the gentle waves of the lake. I was smoking a nice Cuban cigar. Eventually, curiosity got the better of me: “So, I am curious; what do you believe about God?”

“Well, I don’t know. My father brought us to church, and he was an alcoholic jerk. The stuff he did to my mother and me…” It went on something like this, and I had to interject.

“I asked you about God, and all you have said to me this whole time was about your Father.” The guy paused. He had not realized what he was doing.

I don’t recall the rest of the conversation, but it illustrated to me just how important it is to think about how we talk about God. How we talk about God is always bound up with our relationships with other people. You can’t do one without the other.

I asked about God, and he immediately associated that question with his father. Why did he do that? Why did he connect them subconsciously?

This association between God and our fathers is something perennial in the history of religion and it is deep in the Western cultural psyche.

Almost everywhere that people started thinking about God, they started associating with God the qualities of their parents, particularly their fathers, and for obvious reasons. Our parents are the source of our bodily existence, the ones who care for us when we are the most vulnerable, and so, their example forms some of our earliest feelings of safety, security, and provision. They form our earliest thoughts on what is ultimate in life, what is right and wrong, desirable or undesirable.

And so you have these analogies that appear both in the Bible and other religions: God is like a mother because God creates us like a mother birthing her child or sustains us like how a mother nurses her child. God is like a father in that since usually men are the physically taller and stronger members of the household, God is powerful and protective like a father. Because of this perception of power, the leader god in most pantheons in most ancient religions is usually a father-god, not a mother-goddess.

Now, if that is all that is, surely with changing times where both parents work, and gender stereotypes are frowned upon, then yes, referring to God as a Father is out of date. After all, women can be strong, and men can be nurturing, and so on and so forth. But is that really what is going on in the Bible? (I would point out to you that there are actually a number of references to God as female and motherly in the Bible as well if you look for them). But the bigger question is this: Is God really just a projection of what human relationships are like? Or is God ultimately beyond all that? If we think of God as a father, how does God show us what he means by that?

And on the other hand are we so different from ancient people? Our culture still experiences something that ancient times experienced: conditional love, absent love, broken love.

According to Statistica Canada, in 2020, there were 1,700 single dads under the age of 24. Also, in 2020, however, there were nearly 42 000 single moms under the age of 24. There were 21,000 single dads between the ages of 25 and 34 in Canada in 2020 where there were 215 000 single moms. Now, there might be lots of reasons and qualifications for these statistics (there are lots of single-parent households that are healthy and happy, don’t take this the wrong way), but it is safe to say that we still, culturally, are much more likely to be missing the love our of fathers on a daily basis than the love of our mothers. And, of course, that says nothing about the many double-parent families where the children have strained relationships with the parents they know.

We still face the same things as the ancient world, just in different ways. In ancient Greece, in cities like Sparta, if a child was not acceptable to the father, it was quite common, even expected, for the father to expose and kill that child. The father’s acceptance was conditional on whether the child was good enough and strong enough. For folks in this culture, they thought it was necessary: men need to be strong to fight wars. Weakness could not be tolerated.

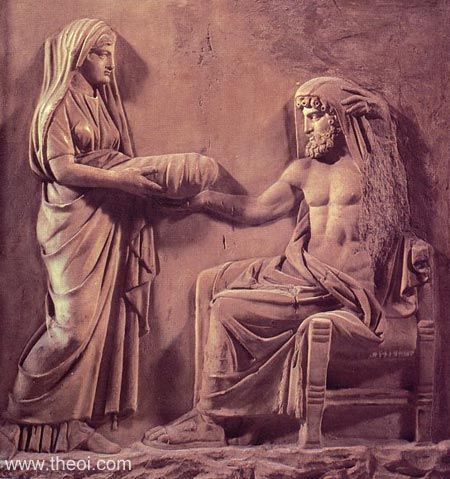

And this struggle to demonstrate one’s strength appears in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, there are two primordial Gods: the mother earth goddess, Gaia, and the father-sky God, Uranus.

They give birth to powerful monster gods called the Titans, the most powerful of which is Cronos, who resents his father’s rule and kills his father, becoming king-god. However, Cronos then becomes fearful that his children will usurp him, so he gobbles them up one by one after each one is born (Greek mythology is strange that way, I know).

However, one of his children, Zeus, is hidden from him and raised in secret, and it is Zeus who grows up to slay his malevolent father, assuming power to reign justly, at least for the most part. Zeus, however, in turn, fathers many illegitimate demi-god children, like Hercules and about 16 others in Greek lore, who grow up not knowing who their father is, often trying to do heroic quests to win Zeus’ approval.

Zeus slays his father, but he can never become a true father, it seems, in turn.

Deep in the religious consciousness of Greek religion is this conflict, this worry: If power is what makes a man, what makes a father, what makes a god, how can any son measure up? (But on the other hand, how can a father ever truly be a father either, if all he is obsessed about is power?) Or if the son is stronger, what is stopping them from replacing or usurping their weaker father, taking what their father has by force? And if that is the case, is Zeus all that different from Cronos? If power is what it means to be man, a father, or a god, then the more Father is like Son and Son like the Father, the more estranged they will be, the more they will fight, whether it is humanity to God or humans to one another. They cannot be at one.

I had this illustrated to me in one of the most profound movies on the effect of absent fathers I have ever seen. It is in the movie The Place Beyond the Pines. Ryan Gosling plays Luke, a motorbike stunt performer for a circus. He is a lone wolf, rough around the edges, a guy from the wrong side of the tracks. However, he learns that his ex-girlfriend had a baby, and it is his. He tells her that he loves her and wants to be for their child what his father never was: a provider that will come through for them. However, he admits that working for a circus does not pay well. He can’t afford the things he believes a father should be able to afford for his child. His girlfriend, however, just assures him that being there is enough. But Luke is afraid that he will be inadequate, just like his father was to him. So, his buddy tells him that if he wants to be a real man and provide for his family, he has to use whatever skills he’s got to do it. For him, it is his exceptional skills on a motorbike that could be used for something else: robbing banks and alluding to cops. Luke, in desperation, agrees. He robs the bank and speeds away from the cops on his bike almost effortlessly, and he is able to take that money and buy a crib and clothes and baby food and even take his family out on a dinner date. However, he realizes he will need more, so, he tries a double robbery, but it goes south, and in the mess of trying to allude to the cops, one cop, Avery, played by Bradley Cooper, shoots him and kills him, even though Luke is unarmed.

At this point, the movie shifts the main character from Luke to Avery. Avery, we learn, is a workaholic cop, being a cop is everything to him, despite him having a young family. For Avery, being a man means being a good cop. However, Avery is stricken with guilt over killing an unarmed man, something a good cop would never do. but Avery’s fellow cops cover up his fatal error, but this does not make him feel better as he learns just how corrupt some of his fellow cops are.

Moreover, he learns that Luke had a son about his son’s age and that the reason why Luke turned to crime was to provide for him so that his own son would be proud of him, the same reason Avery joined the police force, to make his dad proud of him. Because of the guilt, Avery can no longer stand to be around his own son, unable to be a father to his own son, knowing how he took some other boy’s father, punishing himself by denying himself a relationship with his own son.

The movie concludes years later. Avery is running for office, a workaholic relentlessly working for government reform, but doing this deep down to make hopeless amends for killing Luke. However, along the way, his son and Luke’s son, both teenagers now, both wayward and troubled from not having a father figure, meet and realize that while initially hate each other, Luke’s son sees the possibility of enacting revenge—they realize that they are the same: one had their father taken by the other, but the other never had his father to begin with, despite them living in the same house. And yet, ironically, sadly, the two of them show signs of becoming just like their fathers, one a reckless wonderer, the other a perfectionist.

The more Luke resented his father, the more he became like him, and this conflict, this estrangement continued from his father to him, but now from him to his son, who, just as ironically, ends up just like him. If our value as men, sons, and fathers is equated with our performance, we will not be at one with each other.

Think about that yourself. For many of us, we had good relationships with our fathers, but perhaps you did not. How has that affected you? Will we choose to see how our fathers are in us, whether this is good or bad?

Well, again, we like to think that we are better than all this ancient barbarism and mythology, but we are not all that different. The same human nature is within us, and there is the same realization: with so many of our relationships, especially ones as important as the ones between parent and child, we are not at one.

And there is an irony to all this with religion: We as a secular society believe that now that we are smarter, more educated, more technologically advanced, more politically organized…more powerful, we don’t need God. Isn’t secular society just one more attempt to kill Cronos all to end up just like him.

“God is dead, and we have killed him,” said the philosopher Nietzsche, declaring that to live in the modern world was to live with a rejection of God as an idea that was useful and meaningful to life. To live in a secular world is to live in a world that has pushed out God, religion, and even objective morality, all in the name of our own will to power. But even Nietzsche worried whether humans were indeed able to live without God.

We live, as George Steiner once said, with a “nostalgia for the absolute.” We live with an awareness that something is missing, something is absent, and for many of us, we live our lives trying to fill that void with something else, whether it is work, achievements, money, sex, or just mindless consumption and entertainment, whether it the socially expectable kind like Netflix or video games or ones less so like drugs.

I had this connection between God the Father and our fathers in a secular world illustrated to me in one of my favorite novels of my young adult: Fight Club.

Fight Club, for those who don’t know this cult classic, is a story about a man who works a meaningless job for a greedy company. His life has no purpose, so he finds himself unable to sleep, passing the time by ordering useless products from shopping channels. However, he meets a man named Tyler Durden, who convinces him to punch him one night after a few beers in order to make him feel better. The man does, and the two start sparing, punching each other. It feels therapeutic for them, so they start up a fight club in the basement of that bar.

Tyler Durden and the main character talk about their past and about God, and both realize that they had fathers walk out on them, and they feel like this is a reflection of what God is like, too. Other men join this fight club, fighting others as a way of expressing their rage over their meaningless lives. Tyler names their struggle in one monologue he makes:

“Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering…an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables—slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy [stuff…he says something else here] we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man: No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war; our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day, we’d all be millionaires, movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Other chapters of these fight clubs start opening across the nation, and Tyler Durden starts manipulating them into cult-like cell groups, sending the men out on missions to vandalize corporations, with the grand scheme of blowing up the main buildings of VISA and other credit cards and banks, effectively resetting civilization. Tyler believes that he is some kind of messiah figure for himself. The narrator explains Tyler’s motives this way:

“How Tyler saw it was that getting God’s attention for being bad was better than getting no attention at all. Maybe God’s hate is better than His indifference. If you could be either God’s worst enemy or nothing, which would you choose? We are God’s middle children, according to Tyler Durden, with no special place in history and no special attention. Unless we get God’s attention, we have no hope of damnation or redemption. Which is worse, hell or nothing? Maybe if we’re caught and punished, we can be saved.”

Do you know people that say they don’t care about God but are living like they are desperately trying to get God’s attention?

And in a secular world, where we live either ignoring God or feeling God’s absence, as well as living in a world where masculinity, our worth as fathers, is so often defined by power as well as the money we make and the stuff we own or achieve, relationships like the ones between child and parent will be marked with conditions and expectations, caught in this vortex of conflict, competition, and estrangement.

If God is not love, no matter whether we run for God, ignore him, disbelieve him, or hate him—if God is not love, we will end up just like him: unloving ourselves.

I say all this to say that there is a longing deep in the heart of humanity, a longing for meaning and purpose, for acceptance and love, and this longing is symbolized in God the Father so often because of the role our fathers play, whether for good or ill, and it is a longing for oneness.

We have to ask a question fundamental to our future as humans: who is this God that we so often look to as a father? Does God care more about ruling unquestioned than loving his children for who they are? Is God the kind of God that will reject us if we don’t measure up? Will God ignore us if we ignore him? Is love conditional? Is oneness possible? Oneness between God and humanity and humanity with each other?

Well, the story of Scripture tells a different story of God as Father. To confess Christ is to attest to how we have found ourselves in a story where the Creator of all that is chooses to create people in God’s image and likeness. Image and likeness was a way of talking about one’s children. A child is in the parent’s image and likeness and so, God makes all people to be his children, making them with dignity, designing them to reflect his character of love as the way they can most authentically be themselves.

This God reveals himself in history, calling Abraham out of his father’s household, out of idolatry, and into redemption, promising to bless and protect him.

This God led the Israelites out of Egypt, a people oppressed and enslaved under idolatrous tyranny, and God told them that out of all the human family, Israel is to be his firstborn, a nation that has a unique purpose in reflecting God to the nations around it.

This God says God is One, the I am who I am, the living God, and this One God longs to be one with us.

This God says that he is like a father. However, even more than that, God is the perfect father, and God, as this perfect father, beckons us home when we have rebelled against him.

And so when we look at the narrative of the Bible, we see this One God revealing who God is in this pursuit of being at one with us in a way that mysteriously takes on—for lack of a better word—different dimensions to God’s self: the God who is beyond all things, infinite, transcendent, and almighty, but is also the root of all existence, the breath of life, the presence of beauty, one in whom we live and move and have our being, the movements of love, known as Spirit.

As the narrative shows, these dimensions relate to one another. God sends his messiah, the king, but a king that is more than another human king; he is God’s only begotten Son, one with the Father. There is no conflict between Jesus and God because they are fully one with each other to the point that when you look at Jesus, you see the visible image of the invisible God. God is not a distant God. He is with us.

The Father sends the Son, Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly enfleshes the presence of the God Israel worshiped but also fulfills the longing for righteousness, this reconciling oneness with all things Israel was called to, and Jesus does so through sending the Spirit.

This story clashes with human sin, however, and it comes to a particular intensity when people reject Jesus’ invitation to step into the oneness of God. John says at the beginning of his Gospel: “The world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him.” We know how this story goes.

Jesus died on the cross, executed by an instrument of imperial oppression orchestrated by the corrupt religious institution seeking to preserve its own power, but also betrayed by the ones Jesus was closest with, his own disciples and his friends. The cross discloses the tragic depth of our tendencies to refuse to be at one with God and others, even when literally God is staring at us face to face.

But it is in these dark moments that God showed us who God is.

For Jesus to die one with sinners, yet one with the Father, reveals God’s loving solidarity with the human form—our plight, no matter how lost or sinful. God chooses to see God’s self in us and with us, never without us. God chooses to bind himself to our fate to say, “I am not letting you go.”

To be a part of the family of God is to trust in Jesus Christ; it is to remember that in these moments of condemnation, we have been encountered by the presence of the Spirit, a love that invites us to see that we are loved with the same perfect love the Father has for his own only begotten Son. The same love that God has for God in the Trinity, God has for sinners, for you, and for me. God is not going to give up on us.

Paul says it this way, “If we are faithless, God remains faithful.” Why? “Because he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim. 2:13).

That is the truth of the Trinity. Trust this. God has made a way for him and us to be one as he is one.

And if God is like this, this suggests ways our relationships can be healed and improved.

Can this propel us to love our fathers more, not merely for all that they have done for us (or have not done for us), but to love them for who they are, to love them as God loves them, to see ourselves in them and reckon with that, with thankfulness, with forgiveness, with gratitude and grace?

Can this change how we think about our own children? If God sees himself in us, can we empathize more with them, seeing ourselves in them, rather than just making sure they shape up to what we expect? To be there for them, love them for who they are, and the journey God has them on.

And God says, “May they be one as we are one.”

Let’s pray…

Longing to be One (Or Alternatively Entitled: Why God is Not an Egg)

Preached at ADC Chapel, January 24, 2024 (some will recognize earlier versions of this sermon from earlier posts on this blog).

In the Gospel of John, John records Jesus on the night of his betrayal, instructing the disciples about many things. He tells them about things like his new command of love and about the coming of the comforter, and here he does something particularly remarkable. Jesus prays for the church.

20 “I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. 22 The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23 I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. 24 Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory, which you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world. 25 “Righteous Father, the world does not know you, but I know you, and these know that you have sent me. 26 I made your name known to them, and I will make it known so that the love with which you have loved me may be in them and I in them.” (John 17:20-26, NRSV)

Here, John uses this language that within God there are two identities (and a third he mentions a few chapters earlier): Father, Son, and the Comforter, Holy Spirit, and these three identities, these persons, these three somethings are one, a mystery the church has puzzled over ever since, speculating on the meaning of person, being, substance, relations, and a whole lot more terminology. Sadly, the Trinity is nothing but terminology for many.

Dorothy Sayers, a Christian novelist and a friend of C. S. Lewis, once joked that she felt like the doctrine of the Trinity was something theologians thought up one day to make life harder for the rest of us. Ya, caught me, Dorothy! While that was a joke, we have to admit that probably most of us at one point have sympathized with Sayer’s feelings on the matter, and for some, that may have been around week 12 of Christian Theology Part One last semester (I don’t know, just a guess). Rest assured; this is not a sermon about why you need to know the historical context of terms like homo-ousia or hypostases, as important as those are. For surely, the Trinity is more than concepts and vocabulary.

Too often, the Trinity is relegated to the equivalent of the appendix: an unnecessary fixture next to our large intestine that some will just eventually have removed. Or worse: Too often, the Trinity is the club to bludgeon the dissenter with rather than a bandage to nurse the sick soul. Most often, when the Trinity is mentioned in some churches, it is to point out just how wrong some people are and how right we are. (And if that is what we think doctrine is meant for, we have missed the point).

Or we try to over-explain. If you grew up in the church, you might have been subjected to quite possibly the most overused theological explanation of all time: “The Trinity is like an _____ (egg!). There is the shell, the yoke, and the white part. Or God is like water because it can be a solid, liquid, or gas.” There you go. Solved it. I don’t know about you, but I just don’t find the idea that God is like an egg all that comforting. And we wonder why Christian beliefs don’t connect with people.

I mean, at least we could have chosen a better food. The Trinity is like waffles: the waffle, the butter, and the syrup poured out like the Holy Spirit. Look, see, there are three, and they are delicious!

The Trinity is like bacon. I can’t think of three aspects of bacon, but if God is like bacon, I want it!

Well, analogies have limits, especially when it comes to mysteries. Dorothy Sayers followed up her joke about the Trinity with a really good piece of advice: if you want to understand the doctrine, you need to look at the drama. If you want to understand our Triune God, look at the story of Scripture. It is here that we encounter the character of God.

To confess Christ is to attest to how we have found ourselves in a story where the Creator of all that is reveals Godself in the history of a people, the Israelites, a people oppressed and enslaved under idolatrous tyranny. This God says God is One, the I am who I am, the living God and this God rescues the Israelites out of bondage to be a chosen people, a nation of priests, to reflect God’s character to the rest of the world, and this One God longs to be one with us.

If you want to know that doctrine, you need to know the drama. And so when we look at the narrative of the Bible, we see this One God revealing who God is in this pursuit of being at one with us in a way that mysteriously takes on—for lack of a better word—different dimensions to God’s self: the God who is beyond all things, infinite, transcendent, and almighty, is also the root of all existence, the breath of life, the presence of beauty, one in whom we live and move and have our being, the movements of love, known as Spirit.

As the narrative shows, these dimensions relate to one another. God sends his messiah, the king, but a king that is more than another human king; he is God’s only begotten Son, yet one with the Father. The Father sends the Son, Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly enfleshes the presence of the God Israel worshiped but also fulfills the longing for righteousness, this reconciling oneness with all things Israel was called to, and Jesus does so through sending the Spirit.

This is probably where it gets confusing for people (and we do not like confusing). What does it mean to be at one? Isn’t all this oneness talk just impractical abstract mystical stuff? Are we right to ask, as modern people, is all this really useful?

Or does it name something we long for? On December 31, 1989, Bono, the lead singer of the band U2, aired the band’s dirty laundry in a radio interview. The band was on tour with an album some regarded as evidence that the band was over the hill. The reality was the band was burning out. Bono had had his first child, and being away from his family was emotionally draining. Another member’s marriage was crumbling. The band was on the verge of breaking up. Meanwhile, members of the band were becoming interested in activism but struggling to make a difference. They were navigating how they could express their religious convictions in music while wrestling with the religious hypocrisy of much of Christianity. When the band got together to write music a few months later, the song “One” came out of a space of brutal honesty about where their lives were and what they longed for. Let me read you a few stanzas of it:

Is it getting better

Or do you feel the same?

Will it make it easier on you, now

You got someone to blame?

You say one love, one life

When it’s one need in the night

One love, we get to share it

Leaves you, baby, if you don’t care for it…

Have you come here for forgiveness?

Have you come to raise the dead?

Have you come here to play Jesus

To the lepers in your head?

Did I ask too much? More than a lot

You gave me nothing, now it’s all I got

We’re one, but we’re not the same

Well, we hurt each other, then we do it again

You say love is a temple, love a higher law

Love is a temple, love the higher law

You ask me to enter, but then you make me crawl

And I can’t be holding on to what you got

When all you got is hurt

One love, one blood

One life, you got to do what you should

One life with each other

Sisters, brothers

One life, but we’re not the same

We get to carry each other, carry each other

Some of you noticed the interconnected themes of love, marriage, justice, religion, responsibility, hurt, blame, differences, and division, all tied to that word Bono keeps singing over and over: “one,” oneness.

Some of you started singing that in your head. Others just sat there wondering why Spencer is quoting old people music. Some might be thinking, “Spencer, isn’t there any recent good music out there you could have quoted to connect with the younger generation?” And the answer is, “No, there isn’t.”

You can fight me on that later, but I hope you all noticed the theme: Oneness. U2, struggling with their marriages and what it means to be one life together, feels like that is one instance of a larger struggle all humanity participates in together. They use the notion in a very similar way to how Jesus uses it in John. In a similar way, my life is bound up with my spouse, how we are one flesh, how we are partners in life, and how we affect each other; God pushes us to see others that way.

“One life, but we’re not the same. We get to carry each other, carry each other.” It is a clue into the very heart and essence of God, just as much as it is an insight into the very essence and longing of our humanity. We are creatures that are connected to each other.

The past few years have continually illustrated the fact that we are connected. I have been thinking about the wildfires we had last year. It was being talked about on the news the other day.

Hundreds of homes were destroyed by a 25,000-hectare fire caused by such dryness that is unheard of for a province that literally has ocean on all sides of it. The weather is getting more and more severe because we are dealing with the effects of climate change that can turn a spark and a few embers into a wildfire the size of a city.

We are realizing that how we treat the environment affects one another. And at the end of the day, all it took was one person to burn some leaves in their backyard, and hundreds of families lost their homes.

We all longed for rain back in June, and then, you know what happened? We got rain, so much rain there was flooding all over the province. Then, a hurricane happened. Now, we are experiencing a strange winter, which is more severe than usual, while the rest of the continent is hit with Arctic winds. Our world is out of balance, and we are disconnected from it and each other.

It is things like a forest fire and flooding that remind us that a city of a million people like Halifax still needs to be a community, depending on one another, needing one another, affected by the choices of one another; that our providences and nation, just like individuals are not self-enclosed, independent, self-reliant units, able to carry one without help or helping others.

We are dependent on the earth and the seas, the fish and the animals, for the very processes of life that sustain us. We are dependent on each other. We are learning the hard way that we are all connected. Where one acts irresponsibly, all are affected, and also, where one suffers, all suffer.

We have been reminded again and again vividly over the last few years that we are all connected.

We are feeling how industrial practices on one side of the world affect farming on the other.

Health practices on one side of the world affect the health of communities on the other.

Wars on one side of the world affect life on the other.

We can’t get away from it. We are profoundly connected, but we continue to ignore this fact, retreating into our little empires of autonomy (some of us even use our Christian convictions to do so).

And yet, our lives are marred with reminders that we are living alienated from nature and each other. We are divided against the very things we need most. We are killing ourselves because we are constantly failing to see ourselves, our fate, and our identity as dependent on others.

We know we need to be one; we long to be at one with each other; we long for unity and harmony where we can all be ourselves, and others can be themselves in peace with the earth, and yet, we are not at one. We have given in to greed and selfishness or just slipped into an easy thoughtlessness, too concerned with the rat race of life.

We find ourselves reliving this story of humanity again and again, which comes to a particular intensity when people rejected Jesus’ invitation to step into the oneness of God. John says at the beginning of his Gospel: “The world came into being through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him.” We know how this story goes.

Jesus died on the cross, executed by an instrument of imperial oppression orchestrated by the corrupt religious institution seeking to preserve its own power, but also betrayed by the ones Jesus was closest with, his own disciples his friends. The cross discloses the tragic depth of our tendencies to refuse to be at one with God and others, even when literally God is staring at us face to face.

But it is in these dark moments that God showed us who God is.

For Jesus to die one with sinners, yet one with the Father, reveals God’s loving solidarity with the human form—our plight, no matter how lost or sinful. God chooses to see God’s self in us and with us, never without us. God chooses to bind himself to our fate to say I am not letting you go.

John records Jesus putting it this way: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” And he counts the ones in front of him, the ones who he knew would betray him the worst—he counts them as his friends.

So often, we are tempted to lose heart, to recoil and collapse under the weight of our guilt and shame, when we think about the state of our world, our complicity in things like racism, war, climate change, consumerism, all the toxic squabbles we see on social media, or just our individual apathy to the needs of others we encounter on a daily basis— there is so much that might cause us to shrink back and say we don’t deserve a better world. We deserve what is coming to us.

To be a part of the people of God is to trust in Jesus Christ; it is to remember that in these moments of condemnation, we have been encountered by the presence of the Spirit, a love that invites us to see that we are loved with the same perfect love the Father has for his own only begotten Son. The same love that God has for God in the Trinity, God has for sinners, for you, and for me. God is not going to give up on us. Trust this. Trust this.

God is the God who, throughout history, stands with the undeserving, the least of us, the oppressed, the god-forsaken, the outcasts, the sinners—all humanity—announcing as Jesus did to the unfaithful disciples: “peace to you,” announcing God’s will for us is and has always been eternal life.

When we are suffering and scared, our cross becomes his cross.

When we are lost and hopeless, his resurrection becomes our resurrection.

This God who is God above has come and walked with us in Christ as God beside us and has redeemed us with the Spirit, leading us forward as God within us and through us, a love so undivided and unlimited, it is making all things one.

As John says, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness could not overcome it.”

And so, John challenges us to be at one with each other in a similar way to how the Father is at one with the Son: “May they be one as we are one.”

He prays for his disciples. He is praying for the church, which means he is praying for us today. In a world that is broken and divided, be at one with each other. Model the kind of empathy, acceptance, reconciliation, forgiveness, and encouragement that says, “I need you; I can’t be me without you; I cannot succeed unless you succeed; If you are hurting, I am hurting; We are one.”

“One life, but we’re not the same. We get to carry each other, carry each other.”

That is Jesus’ prayer. God knows I could use some prayer on this. I had my family call me from Ontario, wondering if I was safe through all the fires and floods. I tried to explain to them that not all people in Nova Scotia live in Halifax (a point that is routinely lost on them), but I also caught myself saying, “I am okay. This does not affect me.”

I caught myself doing something we all too easily do: since hardship or oppression does not touch my immediate experience, my job, and my family, I conclude I am not affected.

We can do that with so many things. Injustice does not affect me. Poverty does not affect me. Illness does not affect me. War does not affect me. That person’s financial troubles, that person’s health risk, that person’s views: not my problem. It’s theirs, not mine. And so, we choose to forsake the invitation into oneness of love again and again.

One reason the Trinity feels abstract is that we so often use it as just one more way to honor God with our lips (and perhaps our cognitive minds), but the reality is our hearts are far from God.

Two days ago, I was driving into work, and CBC radio mentioned police charged a guy with accidentally starting the fires, as I mentioned before. A 22-year-old decided to burn some dead leaves in his backyard. I remember uttering things to myself about what I hope that guy gets for being so stupid and thoughtless. But then the radio had an interview with a man who had lost his house, his farm, and even his cottage on the other side of the forest fire. The man was asked how he felt about the person charged, and all he could say was, “I can’t blame him. I’ve done a lot of thoughtless stuff over the years. Mine, thankfully, just didn’t have as severe of consequences as his. His mistake could have just as easily been mine.” I remember sitting in my car in the parking lot, just having a moment to take those words and that profound lesson in humility I just experienced. To the one who had caused all this destruction, this man who had every possession of his destroyed in those fires chose to see himself in the other. He chose empathy and mercy. He chose oneness.

Again, folks are so often tempted to see the Trinity as some abstract idea (and we theologians can admit some part in that), but the Trinity flows from our relationship with God and each other. It is an invitation into the movements of worship and prayer, service and sacrifice, solidarity and forgiveness that speaks to the essence of who God is and who we are and the only way we can move forward as people: We are connected; we belong to one another, and in God’s choice to be bound to us, to refuse to let us go, we are awakened to our responsibility to others—more than this: our privilege, our witness, “so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

May we, daily in choices, grand or small, step into the oneness of God as a college, a community, a church, awaiting the day when God is all in all.

The Spirit without Prejudice and Justified Equality

Now before faith came, we were imprisoned and guarded under the law until faith would be revealed. Therefore the law was our disciplinarian until Christ came, so that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer subject to a disciplinarian, for in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith. As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise. My point is this: heirs, as long as they are minors, are no better than slaves, though they are the owners of all the property; but they remain under guardians and trustees until the date set by the father. So with us; while we were minors, we were enslaved to the elemental spirits of the world. but when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children. And because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir, through God. (Galatians 3:23-4:7, NRSV)

The year is 1591 in Scotland, a women named Eufame MacLayne is pregnant with twins and goes into labour. The labour is difficult, physically and emotionally taxing. It is painful. So painful that she pleads with the midwifes for relief. Out of compassion, they give her a strong pain-relief drug. She delivers her babies.

This might seem like a reasonable thing, but in the 16th century it was illegal to use pain-medication for child-birth. The ecclesial authorities learn of this crime, and bring the young mother, still recuperating from child birth before a tribunal.

Her crime: trying to lessen God’s curse on women. God mandated in Genesis 3 that women, due to their sin of eating the fruit, should suffer during childbirth, and how dare Eufame MacLayne be so obsessed with her own freedom and bodily autonomy that she would absolve herself of God’s punishment on her gender.

The church tribunal deemed her guilty. Her punishment was no mere parking ticket: She was burned at the stake. Let that sink in for a second.

Genesis 3 the woman’s pain in child bearing is increased, and this is a sign of the fallenness of our existence. The church in the 1600’s deemed it their duty to enforce the curse, to enforce our fallenness, to enforce the consequences of sin. I find that tragically odd. One would think it is the church’s duty and pleasure to undo the curse. One would think!

Notice also in Genesis 3 that as a result of the man and the woman choosing to go against God, turning in blame towards one another, our lives as gendered individuals are marred by competition, and sadly, but patriarchy: : “your desire will be for your husband, but he will rule over you.” The companionship of one flesh in Genesis 2 is sundered into the barriers of sin: rather than mutuality, hierarchy, rather than reciprocity, domination.

Sadly, many churches to this day deem it their duty, much like the church did to Eufame MacLayne’s day, to enforce the curse, setting up barriers to women in ministry, refusing to recognize women in leadership, whether in the home or church or in business or in educational institutions.

The year is 1860, America stands on the brink of civil war between North and South, largely over the issue of slavery. The Baptist Convention, for those who were listening in Dr. Maxwell’s classes, has already broke asunder, as the North barred Southern Baptist slave-owning candidates for missionary work. Southern Baptist preachers defended the right to own slaves as biblical, and moreover, the right to own black slaves for they are dark skinned and therefore under the curse of Ham. Once again, it is the church’s duty it felt apparently to enforce the consequences of sin, rather than undo them.

The North, lead by Baptists like Francis Wayland, argued scripture must be read through one’s conscience, which deems it unconscionable to own another human being. The South saw this as liberalism. The Bible has slavery. “It says it, that settles it.”

The South, as history shows, looses the civil war, the slaves are freed, but in the wake of this defeat, many Southern leaders flow into the ranks of the KKK, and by night carry out brutal intimidation and lynchings, an estimated 5000 lynchings happened over the next decades.

We like to high-brow our American neighbours, but Halifax tells of its own injustices. In 1960, those who lived in Africville, had their homes and their church bulldozed, forcibly relocated so that the MacKay Bridge could be built.

In the name of economic progress, the land and homes of the marginalized are always a reasonable price.

The year is 2020 we are seeing this today, with the fight of the Wet’suwet’en over whether a pipeline can go over their land. If the Wet’suwet’en were White, would we be so eager to ignore their voice?

The dismissive mentality of many Canadians reflects an old habit of the colonizer who came empowered by the doctrine of discovery, that if explorers found a land not governed by Christian lords, it was their right and duty to take over that land to absorb it into Christendom.

It was their duty to re-culture the natives into Christian culture, the tragic folly of this is evident to us in the estimate 6000 children who dead in the squalor and abuse of the residential school system.

I want to tell you that these horrific things were done by godless people, by those that do not know the Bible. The reality is far more sobering: All these deeds were perpetrated by those who chapter and verse’d their injustice.

This truth makes this message all the more urgent today. It makes the work of your studies, of this college, work of organizations like Atlantic Society of Biblical Equality, the holy fellowship I see in this room, all the more necessary: The Bible must be read through the eyes of equality, which is the eyes lightened by the Holy Spirit.

1. We must read the Word of God with the Wind of God

This is a sermon that cannot stand alone for there is so many passages well-intending Christians have invoked to close down equality: Eph. 5, 1 Cor. 11 and 14, 1 Tim. 2. I can’t treat them here, and why I think there are strong reasons why they are often read out of context.

I would hope to impress upon you the necessity that we must read the Word of God with the Wind of God, Scripture by the Spirit: for “the letter of kills, but the Spirit gives life,” says Paul.

We must read the Word of God with the Wind of God. Words spoken without breath will be nothing but a mute whisper in this world.

Or as William Newton Clarke, one of the first Baptist theologians to consider biblical equality for women’s ordination, writes in his profound little memoir, 60 Years with the Bible, “I used to say the Bible closes me down to this, I now realize the Spirit of Scripture opens me up.” I would hope to impress this on you today.

Why? Because the Holy Spirit opened Paul up, in Damascus first, and then, here in Galatia.

As the early church expanded beyond Judea, the Apostles saw the Spirit’s reach exceed their grasp. The book of Acts shows the wonderful accounts of the Spirit disrupting and unsettling and spurring on and causing the church to reach out.

In Galatia we see Gentiles coming to faith in Jesus Christ and wanting to be apart of existing communities of Jewish Christians. But this created a problem: if Gentiles want to be apart of the people of God, a group called the Judaizers insisted they have to become Jewish.

How do you become Jewish? By submitting yourself to the law, which begins in its epitome, circumcision.

As Markus Barth pointed out, circumcision was the church’s first race issue. Here a religious command becomes a racial issue. Jew: circumcised therefore clean; Gentiles: uncircumcised therefore unclean.

How did the Spirit open up Paul? He realized that the Spirit is without prejudice.

2. Because the Spirit is without prejudice, we are justified by our faith

“Did you receive the Spirit by doing the works of the law or by believing what you heard?” Did you do something to make God love you or did God love you and you just had to trust it?

Gentiles who were not circumcised, who were not setting out to live out all 613 some-odd laws of the OT, or to becomes Jews by circumcision, never the less, had the Spirit come upon them.

One should note, Paul does not have a problem with obeying what God has commanded here. People forget that Paul actually tells Timothy to get circumcised in order to be a more effective minister to his Jewish brethren. 1 Tim. 1:8 says, “we know that the law is good, if one uses it legitimately.” Obedience is not the problem, using the Bible to justify inequality is.

If you are obeying the letter of the law in such away as to delude yourself that this is why God favours you and why you are better than others, why it reinforcers your privilege and superiority against another, you have made the law do something it was never intended to do. And that is what the Judaizers were doing.

Paul responds, “no one is justified before God by the law, the just will live by faith.” He is quoting the Old Testament here. That is what the law is supposed to remind us of. Trust God’s mercy; trust what his Spirit is doing.

That is what qualifies us to be the people of God. This is what makes you a child of God. Period.

Paul then does something profound. Just as Jesus transgresses the letter to fulfill it spirit, Paul says, if that is how you are going to use circumcision. I’m ending it. It’s done.

We often fail to appreciate just how radical this is.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer once said that “The Pauline question whether circumcision is a condition of justification seems to me in present day terms to be whether religion is a condition of salvation.” That is how radical, progressive, and revolutionary Paul was being.

Circumcision is considered the eternal ordinance in Genesis. But I it got in the way of knowing Jesus. If it got in the way of God’s love. It got in the way of what the Spirit was doing. Well, circumcision just didn’t make the cut no pun intended.

Paul called into question the very centre of his Jewish religion in the name of the love of Jesus Christ. Brothers and sisters, we have to ask ourselves, are we going to follow the Spirit, even if that means forsaking our religion too? I hope so.

3. Because we are justified by the unprejudiced Spirit, we must remove all barriers to equality

At the apex of the epistle to the Galatians, he offers this powerful manifesto: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise.”

Jews and Gentiles are equal in Christ, therefore the physical restriction of circumcision, dividing the two, was removed in the name of what the Spirit was doing.

In Galatians the act of the Spirit is without prejudice in bestowing the gift of salvation, by it we cry out “Abba Father.” In 1 Corinthians 12, Paul lists the same manifesto before listing the gifts of salvation. Verse 12:

For in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit….

Jump down to verse 28 where he lists the result of drinking of the one Spirit: And God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers; then deeds of power, then gifts of healing, forms of assistance, forms of leadership, various kinds of tongues.

Notice that apostleship is in this list, notice that leadership is in this list. If the Spirit is without prejudice in bestowing the gift of salvation, by this same logic the Spirit is without prejudice in giving the gifts of salvation.

Equality of the gift and gifts is part and parcel with the logic of justification by faith. You can’t have one without the other. Because we trust that the Spirit has brought us Gentiles into the people of God, we can’t help but trust the Spirit also calls anyone, regardless of race, gender, or status, to lead his church. You can’t have equality without justification, and you can’t have justification without equality. Gift and gifts are one as the body of Christ is meant to be one.

It would be a gross error in judgment to think that just because Paul is working within society with slavery that Paul is not trying to subvert slavery.

It would be an equally gross error in judgment to think that just because Paul is working within a culture that saw women as subordinate, that his writings are not trying to gently subvert this either.

The church has not done well to notice this, but the Spirit is without prejudice, we are justified in equality, and that is why the physical barriers to this new humanity must come down.

Interpreters from Martin Luther to recent commentators like Ronald Fung have been content to say that this manifesto only pertains to spiritual equality. In faith, slave and free people are spiritually equal, despite one owning the other; men and women are spiritually equal, despite women being subordinate to men. In the words, the barriers to equality in our bodies don’t matter. In other words, dualism.

This does not take into account the bodily nature of circumcision. And if you don’t feel like circumcision has something to do with bodily equality, men, you just have to ask yourself: if a church expected you to be circumcised in order to be a member, imagine if they said that in the bulletin, would you really feel welcomed? The issue of equality is very much a bodily matter.

Women’s equality, racial equality, economic equality, they are all very different and need to be addressed in very different ways, and yet they are connected. We cannot have equality from one without equality for another. Why? We are all human. We did not choose the skin we are in.

I have no control over the circumstances of my birth: I could have been born female; I could have been born native or black; I could have been born in a country ravaged by corruption; I could have been born with a developmental disability or a severe mental illness. Let me push you further: I could have been born with XXY chromosome syndrome and fallen outside the gender binary. I could have been born with testosterone deficiency, and thus been bodily female yet a chromosomal male. That is exceedingly rare and our political discourses have surely marred this discussion, but the fact remains: I did not choose the skin I am in.

If that is the case, with the social barriers out there today, the stereotypes, we must all ask ourselves, if this could have been me, how would I want to be treated? Equality must be our guiding principle, empathy and conscience must guide our interpretation, because Paul says later in Galatians, the whole law is summarized in one command: “Love your neighbour as yourself.”

And if we don’t, as Desmond Tutu once said, “If I diminish you, I diminish myself.” Because I could have been you. “We are a lot more alike than we are different” (Charlie Taylor).

Some see bodily differences as the reason for social barriers, the Bible sees our bodily differences as what necessitates the hard work of physical equality. Our physical differences are what makes the equality of the new humanity all the more beautiful.

4. The cost of equality is worth it

About ten years ago I was pastoring in another Baptist denomination that was founded in part by the rejection of women in ministry. I found myself in seminary zealously against women in ministry. Back before this in seminary, my first year of bible college, I wrote a paper why the egalitarian professor at my Bible college, Dr. Bill Webb, should be fired for his liberalism. A word to the wise, don’t ever write a paper about why your professor should be fired. My professor, a lady named Lisa Onbelet, very graciously asked me to rewrite this paper.

Yet, when I took Dr. Webb’s hermeneutics course, I found him able to give gentle, articulate answers about the scriptures I quoted at him, such that I found myself convinced. And this is good advice for anyone as we have these conversations: be gentle and be patient. Know your Scriptures.

Bill was eventually let go from his position, and we all knew it was due to his convictions.

When this happened, I knew that this would have consequences for me as I began to pastor. As I sat down with the leadership of the association I was apart of to discuss further funding for a church plant in the next town over, talk of ministry turned to talk of theology, and the leader wanted to know if I was in or was I out.

I could have remained silent, our first child, Rowan, had just been born. I was doing full-time doctoral studies, working 10 hours week as a TA, 10 hours a week as a soup-kitchen co-ordinator, 20 hours a week as a church planting intern. Meagan had gone back to school on her mat-leave to upgrade her teaching degree along with life-guarding in the evenings. We were barely scrapping by.

I could have stayed silent, but I knew that I couldn’t. I would not be able to live with myself if I denied my conscience and my convictions.

The association leader gave an ultimatum then: shut up and toe the party line or have your funding cut. I pleaded with this man for several hours over coffee to no avail.

“Why can we not centre our denomination’s unity and how we do the Gospel on something like the Trinity, who God is?” I insisted. His response, which I had to write down because I couldn’t believe it, he said, “No, Spencer, gender roles is more important to the Gospel than the Trinity.” For many Christians that is the case.

That night I said to Meagan I am going to have to fire up my resume and leave the denominational family my grandfather, Fritz Boersma, was a founding pastor. After dozens of resumes were sent out and no call-back, no church wanting to hire a doctoral student, but finally First Baptist Church of Sudbury called.

In hindsight this was a small cost in the end compared to women I knew that studied at this Bible college to realize no church would ever take a chance on them no matter how talented or passionate or godly they were.

There is still work to be done. I just got a message from a woman wishing me luck and she mentioned she was speaking with her church about why they can have women pastors. I realize I will never have to do this. I will never have to justify my profession or my vocation because of my gender. That is precisely why I am saying this now.

But it was a wonderful experience pastoring a church that had long supported women in leadership, cultivating a thoughtful open-minded community, but also I can tell you that while our denomination or congregations as a whole upholds equality in principle, it still has a long way to go in practice.

Whether it is women’s ordination or reciprocity in marriage, racial justice, indigenous reconciliation, hospitality to refugees, dignity rather than disgust for sexual minorities, or seeking to treat those who face poverty with the material support a person made in God’s image deserves, each one of these were weekly struggles in pastoring.

With every new face around the church came the question of what toxic, half-baked, youtube-google-searched theology are they bringing in with them. Many I found have built their entire faith on staying safe. Many love justifying social barriers with scriptures. Many Christians love treating the New Testament as the second Old Testament, shall we say.

There is that option pastoring and in preaching when you know a sermon illustration that the text calls for will upset important members of the church who are set in their ways and each month you know the church’s budget is holding on by the skin of its teeth, it is easy to just not talk about these matters and offer people a comfortable, spiritualized Gospel.

I was pleased and humbled to have First Baptist Sudbury grow well in my five years there, but I know it also came with one sermon after another where so-and-so wasn’t there the next week, all to find out that they didn’t like being “pushed on those issues,” and eventually “moved on” to the next church in town.

I also found pastoring that just as many women were opposed to equality as men were. For some, the notion of being restricted meant they don’t have to be responsible and don’t have to worry. The idea that God might call them to something more risky and vulnerable and messy, well, subordination meant safety.

After all, the Israelites wanted to go back to Egypt, didn’t they?

Proclaiming God’s word will cost us. It will cost us in a culture that has fractured into tribes of self-interest. It will cost us pastors even more as we pastor churches that have too often created cultures that cater.

I worry that there are many that want to ignore this conversation on equality let alone our duty to uphold it. And from a worldly perspective, why should I as a Western, English-speaking, white, straight, middle-class, male be asked to give up something for people I don’t know? One might say, “White privilege? Life is hard for me too you know!” If freedom is the point of rights, why would I give up my freedom for another’s rights?

But for Paul, this is not his line of thinking, and it can’t be ours. His equality is founded on the God who took on our flesh, “born of a women, born under the law.” A God who gave up his freedom so that we could be free.

We are equal because the barrier of heaven and earth was broken, because the king became a slave, because the holy one took on our curse, the blessed one took on our cross, because the righteous one became sin, because the first became last, because God removed every barrier between God and sinner with his very body, so that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come… nor anything else in all creation, can to separate us from the love of God; because of this, we are one, we are free, we are saved, we are blessed, we are counted as God’s people, considered God’s children, inheritors of the kingdom of heaven itself. Living this out is our equality.

God bore the cross so we could be free, and now we must bear our crosses so that others can know this freedom.

Equality will cost us, but I also know there is so much more to be gained, when we see churches that embrace all the gifting of the Spirit regardless of race, gender, or status. This is when the kingdom shines through the beautiful mosaic of Christ’s body all the clearer. The cost is worth it.

Because the kingdom is Paul’s equality, he is able to say, I am willing to endure hardship, hunger, persecution, peril, even the sword, to make this equality possible for another, especially those whom this world as forgotten. He is able to say, for him living is for Christ and to die was gain. The cost is worth it.

May we die to self today, and may we embrace new life in Christ.

May it be the case for us today and hereafter.

Let’s pray. [Given the topic of this sermon, I am going to take a different form then the normative pattern of prayer to the Father in the name of Jesus, and actually, pray to the Holy Spirit as the Book of Revelation does]

Holy Spirit, Spirit of Christ addressing us now, Sophia-wisdom of the Father before all creation.

You hover over the deep of our soul with a creativity that formed the heavens and earth.

In you we live and move and have our being. We sense you in our midst; we feel you groan with sighs too deep for words over the state of our broken world.

Forgive us for neglecting you. You are the Spirit of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law. You make the equality and freedom we seek possible.

Forgive us for the ways we have refused to see the image of God in another. Be with the marginalized of this world. Give eyes to see them and ears to hear them.

Be with our female pastors, who face barriers our male pastors do not. Be with our pastors that work for racial equality, indigenous reconciliation and care for those in poverty. Call us all to work for equality in all forms, even if it costs us. No cost compares to the riches of your kingdom.

We thank you that by your love we are justified, by you we cry out “Abba Father!” Teach anew to read scripture with your refreshing breath; breathe upon us the fire of Pentecost to speak your Gospel to the cacophony of this world.

But remind us that the same gentle presence we sense here as we sing is the same that raised our saviour Jesus Christ from the grave. May we never forget it.

By you one day the earth will be filled with the glory of God as water over the sea, by you every knee will bow and tongue confess Christ is Lord in heaven and on earth and under the earth, by you, God in Holy Trinity, will be all in all.

Come, Holy Spirit, Come. We thirst for you.

In Jesus name, amen.