So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. – Galatians 3:26-29

The other day I was told by a complementarian (a person who upholds that there is a hierarchy between men and women as taught by Scripture) that if I believed that women could be ordained, I no longer believed in the authority of Christ over the church. I supposed by this person’s logic and theology of a chain of authority, if he was correct, this is true. However, I don’t think complementarianism is the best exegetical account of the whole of the Scriptures, and so, here is my gentle push back on what is at stake if complementarians refuse a woman in her ministry gifting. It is my intent, as my deliberately provocative title suggests, to demonstrate that Galatians 3:28, within the context of the argument of Galatians and implicit within the same logic of justification by faith, cannot support patriarchy in the church, especially if leadership is by the gift of the Spirit. As a religious axiom about the gift of the Spirit, it promotes the equalized distribution of all spiritual authority without prejudice. If authority in Christian marriage and church is based on the Spirit, this Scripture supports an egalitarian understanding of both.

Understanding Paul’s Concerns

In doing so, I want to chart a middle ground between what I see as the “civil rights activist Paul” and the “complementarian Paul” readings. Both try to fit a circle into a square hole. Notice also, that this is not “conservative version of Paul” versus the “liberal Paul.” There are biblical conservatives that espouse egalitarianism (such as myself), meanwhile, there are complementarians who are such probably for no other reason than their culture has caused them to read scripture thus.

In the context of Galatians, Paul is not concerned with a modern grammar of woman’s rights. It would be wrong headed to translate his world into ours, making him into a modern feminist. All benefit to society is enacted indirectly through the practices of the church, within its narrative self-understanding, not political advocacy directly through a universal set of principles. He is concerned with making sure all recognize what the Spirit has done. Paul is concerned about emancipation and gender equality, but his way of going about it is focused firstly on life in the Spirit in the church community. He is not a civil rights activist. He is not political. He has very little confidence in the justice of the Roman government. His concern is for equality in the life of the church as a witness to the world. So, Paul is primarily concerned about spiritual equality in the church (as opposed to political equality that bypasses the church), but that in turn has very real practical consequences. For him, there can be no ultimate dichotomy or between spiritual value and practical role and no discrimination of the gifts

In Galatians, Paul is concerned with Judaizers imposing the requirement of circumcision on Gentile Christians in order for them to be considered full members of God’s family (4:5), Abraham’s offspring/heirs (3:7) and recipients of the covenantal blessing/inheritance (3:19). This context, as it applies to gender, implies inequality as Paul is equalizing Jews and Gentiles.

Paul sees those advocating circumcision as acting out of discontinuity with the acts of the Spirit. The expectation does not match what they are seeing. In compelling circumcision and austere obedience to the law (the former being a metonym for the later), Paul worries that this is simply disingenuous to the event of Christ’s grace on all who believe and therefore detrimental to anyone that buys into it. It becomes “another gospel” (1:6) as it falls into a paradigm of meritorious obedience, which is an unsustainable perfectionism (3:11-12): the law cannot produce justification because those who seek justification by the law are obliged to keep all of it for that to work, which obviously no one can.

Also, imposing circumcision on Gentiles seems unloving (5:6), especially if it is unnecessary. You can imagine how the Gentile men would not appreciate having to cut a piece of their genitalia off in order to appease the unnecessary demands of a religious faction! It would be painful, humiliating, and potentially unsafe (although Paul does not explicitly mention these factors). The act of which implies ethnic superiority, and inequality as well as religious hypocrisy in Paul’s mind as it treats Gentiles by a double standard that even Peter did not follow. Gentiles were being treated as inherently impure, warranting the circumcision faction and Peter refusing to sit with the uncircumcised in table fellowship (2:12), and therefore they are expected to “act like Jews” (2:14) in order to be acceptable.

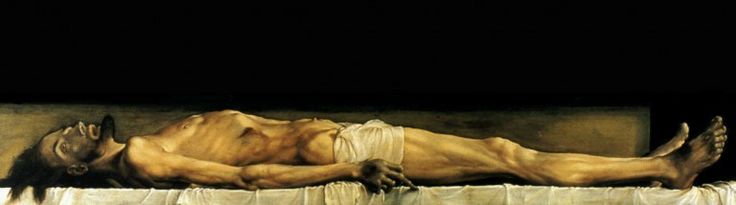

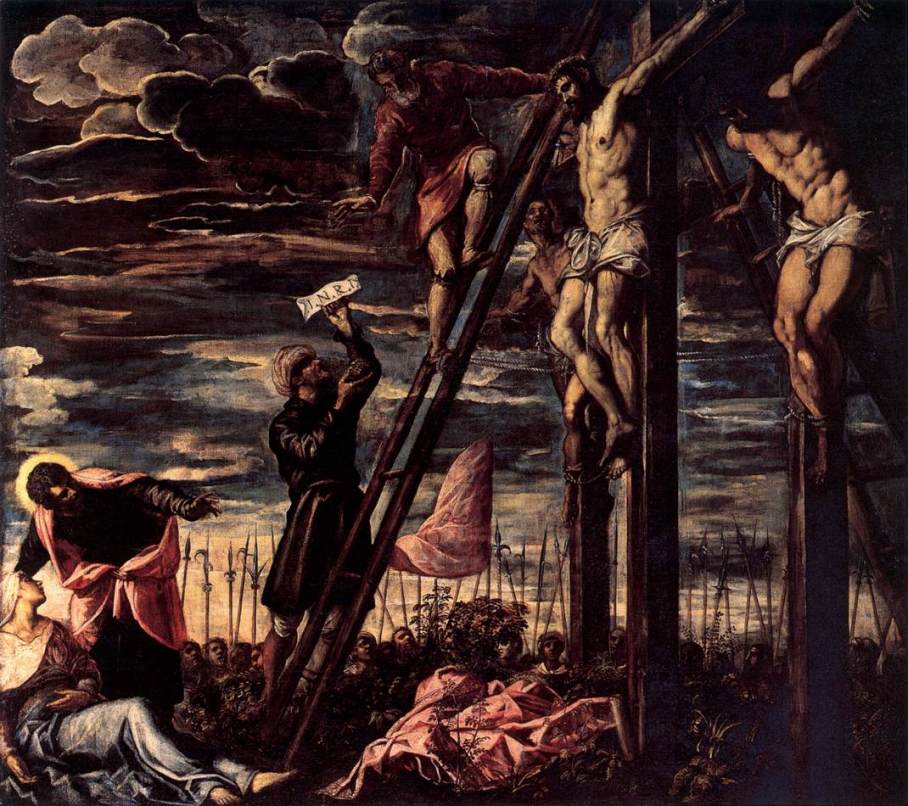

However, the work of Christ undoes the basis of superiority here. Paul argues that Christ, who died on a tree, took on the cursedness of those separated from God, existing outside the law and covenant, and in so doing redeemed those under the curse (3:13-14). Any blessed/curse, clean/impure distinction is therefore absorbed in Christ. Paul’s logic presupposes quite a bit in 3:14, but it implies that Jesus is the Son of God (2:20) as well as the offspring of Abraham par excellence (3:16) and by dying on the cross, the Gentiles now have the inheritance and blessing of Abraham as if they too are his offspring. The inheritance is the gift of the Spirit (3:14). This gift of the Spirit, making possible new relationship, occurs by trusting the work of Christ alone – justification by faith – not by meritorious obedience. Since the Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, God’s Son, those who have the Spirit, are therefore also God’s children, able to cry out as Christ did, “Abba! Father!” (4:6). Paul’s argument then has an experiential base: he has witnessed uncircumcised Gentiles, who do not uphold the entire law, be granted the gift of the Spirit purely because they trusted Jesus, and so, he continues to encourage the Galatians to stick with this paradigm.

This overcoming of cursedness and uncleanliness implies a powerful social revolution in Paul’s thought through the work of Christ. We miss it because we expect him to argue on the basis of civil rights. Women were often restricted because of the uncleaniness associated with their gender. For example, Lev. 12:1-5 states that a woman who has given birth to a boy is ritually unclean for 7 days. If the baby is a girl, the mother is unclean for 14 days. Male babies, therefore the male gender, was considered more clean than then female babies. Women had to go into seclusion during their menstruation cycle, because they were unclean (Lev. 15). Thus, women were restricted in worship. Second Chronicles 36:23 states that women were not allowed in the sacred space of the temple as they has their own space, considered the least sacred.

Thus, given that women were treated as as less pure in the ancient world, the notion that Christ bore the curse of the law and that true impurity is wrong doing (Matt. 15:11) would have opened up unprecedented liberty in Jewish culture.

Pneumatic Equality

Some might press the notion that Galatians is only about spiritual equality, so let’s explore it further. Here we see that all are given the Spirit through faith in Christ, which has very practical consequences. Paul is advocating what we might call “pneumatic equality.” Paul does not mention what the nature of the gift of the Spirit does beyond causing adoption and spiritual fruit. Nevertheless, Gal. 3:28 insists that whatever the gift of the Spirit is, the gift is given indiscriminate of ethnicity, economic status, or gender. Whatever the gift of the Spirit entails, it is applied indiscriminately for “you are all one in Christ Jesus.” This is the argument for equality that this passage implies. If one had something or another could not have something on these premises, the result is inequality.

To be clear, Paul only talks about the gift of the Spirit in general principle, but the principle is strictly egalitarian. Complementarians can only at best downplay the importance of the principle, silencing it with other scriptures that sound more complementarian. Thus, if the gift of the Spirit implies all the gifts listed elsewhere in Paul’s writings (cf. Rom. 12:6-8; 1 Cor. 12:8-10; 1 Cor. 12:28; Eph. 4:11, which include the gift of apostles, prophets/prophecy, teachers/teaching, leadership, administration, etc.), the criteria of their distribution should be, by this principle here, indiscriminate of gender as it would be of race and income inequality. It implies that if a Jew can speak in tongues so can a Gentile, if a free person can be a prophet, so can a slave, if a man can have apostolic gifting, so can a woman. Anything less amounts to the denial of the promised inheritance for some.

Thus, it should not surprise us that the Spirit has been so indiscriminate, even in the Old Testament. There we see Deborah, a prophet and judge over all Israel, despite the qualifications a judge in Exodus 18 stating “men who…” (which would form the paradigm of reading the elder descriptions that refer to “a man who…” in 1 Tim 3:2 and Titus 1:7 as generic, inclusive, or non-absolute). Also we see the formidable prophetess Huldah (2 Kings 22: 14-20), who has the God-given authority to rebuke the king himself. We see Philip’s daughters, who are prophetesses (Acts. 21:8-9). There is also Priscilla, who seems to be an apostolic co-worker with Paul along with her husband (cf. Acts 18: 24-26; Rom. 16:3-4; 1 Cor. 16:19; 2 Tim. 4:19); Chloe, whoever she is, seems to have authority in the church of Corinth such that her people report to Paul (1 Cor. 1:11); Phoebe, who seems to be a deacon of Cenchreae (Rom. 16:1) come to give the church in Rome direction; Nympha, who has a church meeting in her house, which strongly insinuates she lead that church (Col. 4:15); Junia, “prominent among the apostles,” which suggests that she is an apostle in the fullest sense of the word (Rom. 16:7); and finally, Euodia and Syntyche, who are listed as leaders along side Clement, which again, suggests apostolic authority (Phil. 4:2-3). If the implications of these passages are correct, this further corroborates the notion that the Spirit does not show favoritism if bestowing the gifts.

Does Justification By Faith Imply Egalitarianism?

Indeed, anything less than an egalitarian application of the gifts of the Spirit would imply legalism. Gentiles, by faith in Christ, are not obliged to follow rules that no longer function, that detract from the work of Christ (which circumcision did), that do not fulfill the law of love (5:6; 5:14) or do not manifest the fruit of the Spirit (5:22). Where there is the fruit of the Spirit, “there is no law against these” (5:23). Conforming to any laws, whether biblical or not, that do not meet these criteria is problematic. If the Gentile believer took on circumcision, such an act would be an act of inequality, reinforcing the superiority of the Jewish ethnicity before God that God has abolished in Christ. Jews and Gentiles have the same access and unity to Christ. Similarly, denying a slave or a woman the Spirit’s gift to preach or to teach, would be in some way saying that they have less of Christ in them than in a free male, implying almost that their submission and slavery was meritorious obedience. Is a complementarian comfortable saying that not all are truly “one” in Christ by faith? This is what the logic implies.

In fact, to take up circumcision as a meritorious action, functionally becoming a Jew in order to be an heir of the covenant, this action seems to imply slavery: “We are children, not of a slave but of a free woman. For freedom Christ has set us free. Stand firm, therefore, and do not submit again to the yoke of slavery” (4:31-5:1). Gentiles, who have the Spirit by faith, have everything the Jewish believers have. Gentiles are able to relate to God unburdened by their previous estrangement from God; they are given the same status, namely, children of God and they are given the same inheritance, namely, the Spirit.

Interestingly enough, that argument could be made, albeit provocatively, that since justification by faith and the gift of the Spirit is linked in Galatians and the gift of the Spirit is for Jew and Gentile, male and female, slave or free, if a person imposed laws of gender on a woman that denied her what the Spirit gave to her through her faith in Christ, that person can be understood to be implicitly denying justification by faith in the same way a Judaizer would be denying justification by faith in imposing circumcision on a Gentile. All are one in Christ.

The Preference of Liberty

This sets an applicable pattern: liberty is preferable to slavery, yet liberty is not to be valorized outside the work of the gospel. This has a very real application for gender. Submission is not virtuous if it does not function, and such submission, especially imposed submission by other Christians, implies inequality in Christ’s unity with humans. It implies slavery. Laws that do not function, should not be followed if they are not loving, do not produce spiritual fruit, or promote the notion that the Spirit is prejudiced. Under these principles, gender and economic equality becomes a secondary concern of all who seek the Holy Spirit to be made more evident in creation.

This does not mean a person who is not given the gift of teaching, for instance, should feel that God is unfair in giving another that gift. What this is saying is that on principle these gifts are given indiscriminate of race, economic status, or gender, and so, not withheld on that basis. There are different roles in marriage, society, and church, the point is that the distribution of these roles cannot be on the basis just described. While we all may be called to serve and submit on mission for Christ, refusing Spirit-given liberty for another, imposing submission, is slavery. Men can be leaders if they have the character, but then again, so can women. A man can be called to be a pastor, if he has the qualities, but then again, so can a woman, if she is qualified. In principle then, a woman could be given any gift of the Spirit just as much as a man could (or Jew, Gentile, slave or free person), but that does not mean every person gets that gift. Men will be called to listen and submit to their wives (“submit one to another out of reverence to Christ” Eph. 5:21), a man must submit to a gifted female teacher as in the case of Huldah and the King (2 Kings 22: 14-20) or Apollos and Priscilla (Acts 18:28). Thus, we see no basis in Gal. 3:28 that any gift of the Spirit is restricted to a gender. To be clear, this does not take offense at the notion that some are called to have authority while others are called merely to submit and trust that authority. The problem lies with any attempt, especially by Christians, to restrict a gift the Spirit sees as open to all, particularly on the basis of ethnicity, gender, or economic status. It does not take offense at the call of some to be enslaved, but see the unnecessary imposition of submission on another.

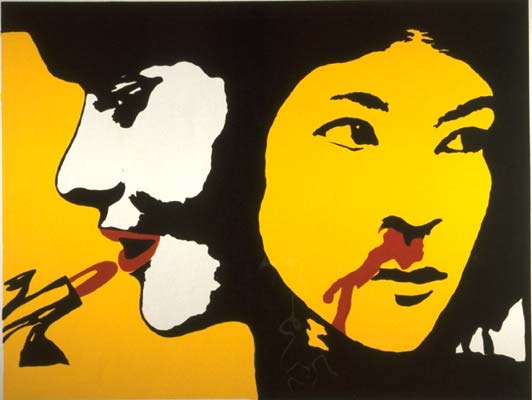

This clarifies the rhetoric often used by the complementarian that women are spiritually equal, but functionally different. There is no problem in stating some are called to different things, while others are not. Some are called to more difficult lives than others. A person, who feels that it is there vocation to be an accountant for God, will be functionally very different than the person called to be a missionary in the undeveloped world. However, if we used the example of slavery and segregation in the United States, the problem is then the church limits the liberty of others, imposing a supposedly God-sanctioned social order that prevents some to pursue a Spirit-given vocation to a position of authority.

Is Slavery a Defeater?

One could object that if Paul did not abolish slavery, the application of the spiritual equality that equalized Jew and Gentile, removing the requirement of circumcision, cannot be fully applied to gender equality.

What the Gospel in Galatians does imply is the notion that all people are God’s children, thus able to cry out “Abba, Father” (Gal 4:6-7) and are heirs of the inheritance. This in a very practical sense meant the elimination of social separation between Jews and Gentiles in table fellowship (Gal. 2:11-14), but also in 1 Cor. 11:17-34 mean the equalization of access to food at the Lord’s Supper. This equality was lived out in the community of goods, where believers sold all individual property and live as if a single household (Acts 4:32). It was a scandal if a member of a church had much and another was in need.

With regards to slaves, while Paul did not seek a full and potentially destructive and violent emancipation, he did insist that all members of a church, whether slave or free, were considered family. If a slave was considered the family of a master, the implication is that freedom would be sought for the slave along with all other facets of general well being. It would be despicable that a person would own a family member as a slave. Thus, we see in Philemon, Paul plead (not force, we should note) that Philemon free Onesimus as the runaway slave (a criminal offense) is “no longer a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother” (Philemon 16).

Some are called to endure suffering and subjection for the sake of the Gospel, including wives (1 Peter 3:1-6) and slaves (1 Cor. 7:21), however, this subjection is for the purpose of witness vocation. Slaves in Christ are free, and the free in Christ are slaves (1 Cor. 7:22). In the case of a slave, Paul recommends not being obsessed with emancipation, continuing on in the state that the person is in. However, Paul clearly expresses the preference that a person must not become enslaved: “You were bought with a price; do not become slaves of human masters.” Again, witness is more important than emancipation for Paul, just as martyrdom is a greater witness than a long and comfortable life. Paul does not easily fit the profile of a social revolutionary. He is an evangelist that sees slavery, hardship and even martyrdom as opportunities to show Christ. However, is social inequality of little significance to Paul? No. Freedom was preferable to slavery.

Again, Paul was not a social revolutionary primarily, but the Gospel does imply liberation. The Gospel implies social progress, but the Gospel does not seek self-assertion let alone violent emancipation to cause progress. Social progress is not the Gospel, salvation to sinners by the free gift of forgiveness in Jesus Christ is. However, the social progress and liberation is a byproduct of redemption as it seeks to remove all barriers to authentic vocation and all effects of sin.

As this relates to gender, the notion that Christians would seek to enshrine and perpetuate limits on women in the home, church, and society, would be going against this principle that Paul offers. Again, Paul is not a human rights activist, and we need to draw close to his logic. He is advocating that the Holy Spirit does not discriminate with regards to the spiritual gifts, some of which imply leadership authority. Refusing to recognized that the Spirit could call a woman to lead, for instance, in the church, is tantamount to limiting the work of the Spirit and perpetuating a requirement of submission that falls back into legalism, subjection to the law.

Conclusion

By analyzing the logic of Galatians 3:28 in the context of the epistle, we see that it offers the principle that the Spirit does not discriminate on the basis of ethnicity, economic status, or gender in regards to the Spirit’s gift, the inheritance of Abraham. Justification by faith implies a type of egalitarianism. Refusing a gifted woman preacher in the church is analogous to imposing circumcision on a Gentile. It is a similar type of legalism. Thus, I offer the provocative push back to some complementarian polemics against egalitarianism, where complementarianism denies justification by faith (which I offer not because I actually think complementarians deny justification by faith, but to point out what the logic implies). While I have worked against the notion that Paul can be absorbed into the caricature of a modern civil rights activist, this does not dismiss the fact that Paul would not allow any inequality in his churches. Refusing to recognize that a woman could have a gift of preaching, prophesy, teaching, administration, or even apostolic leadership is to go against the Galatians principle here.